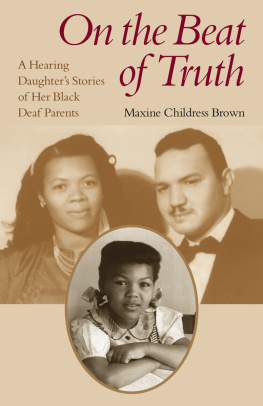

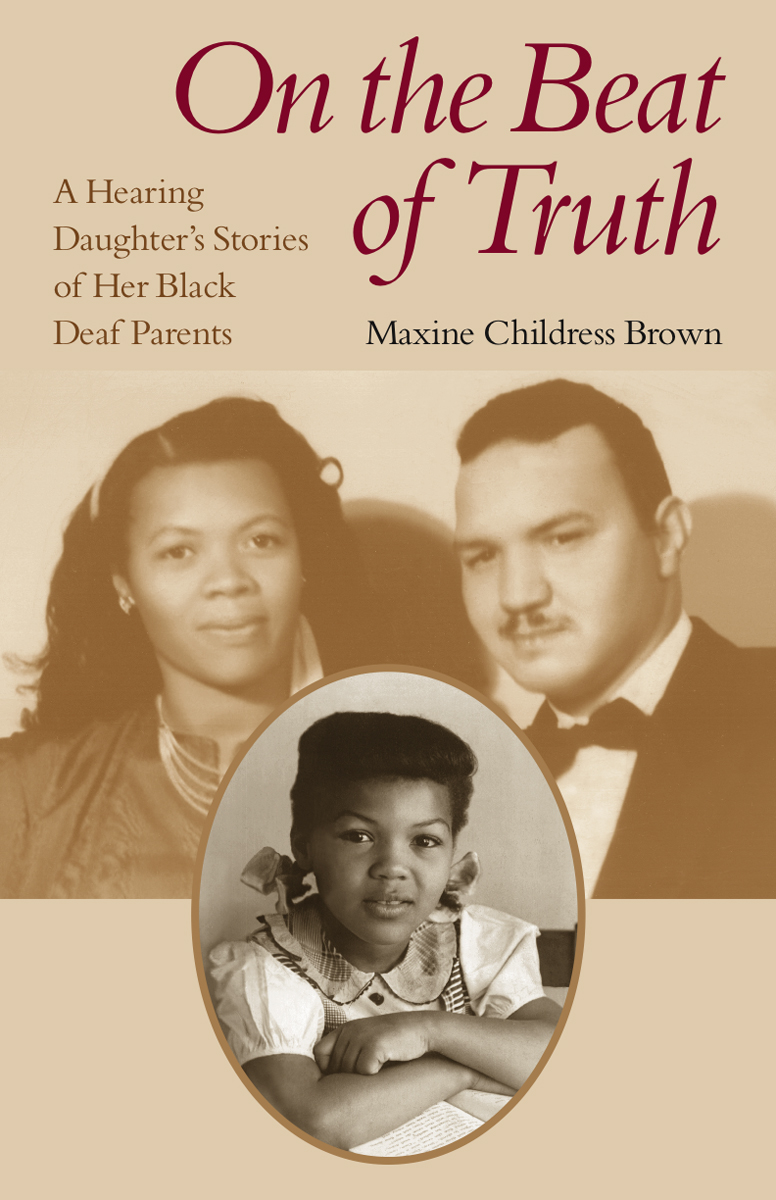

On the Beat

of Truth

Copyright 2013. Gallaudet University Press. All rights reserved. May not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher, except fair uses permitted under U.S. or applicable copyright law.

EBSCO Publishing : eBook Collection (EBSCOhost)

AN: 1215138 ; Maxine Childress Brown.; On the Beat of Truth : A Hearing Daughters Stories of Her Black Deaf Parents

ON THE BEAT

OF TRUTH

A Hearing Daughters

Stories of Her Black

Deaf Parents

Maxine Childress Brown

Foreword by Scot Brown

Gallaudet University Press

Washington, D.C.

EBSCOhost - printed on 2/7/2022 2:59 AM via . All use subject to https://www.ebsco.com/terms-of-use

Gallaudet University Press

Washington, DC 20002

http://gupress.gallaudet.edu

2013 by Gallaudet University

All rights reserved. Published 2013

Second Printing 2016

Printed in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Brown, Maxine Childress.

On the beat of truth : a hearing daughters stories of her black deaf parents / Maxine Childress Brown.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-56368-552-1 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-56368-553-8 (e-book)

1. Brown, Maxine Childress. 2. Brown, Maxine ChildressFamily. 3. Deaf parentsUnited StatesBiography. 4. Children of deaf parentsUnited StatesBiography. 5. African Americans with disabilitiesBiography. I. Title.

HV2534.B75A3 2013

362.423092dc23

2012046554

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984.

My mother, Thomasina Brown Childress

who loved her children unconditionally

and

My father, Herbert Andrew Childress

who struggled all his life

James Brown, my beloved husband

Our three marvelously talented children:

Scot, Nikki, and Kimberly

My two gifted sisters: Shirley and Khaula

Dear sweet aunt Mary Magdalene Minor (Babe)

Brother Pascal, a Trappist Monk of the Abbey of the

Genesee, who viewed life with a childs innocence

and

Dr. William Talpey, a gifted pediatrician,

who loved flowers as much as my mom

and

Finvola Drury, an extraordinarily dedicated

teacher who insisted I had a story to tell

Contents

Scot Brown

Foreword

Scot Brown

Everyone has a story, and is the product of many more stories. The peoples historian elevates and exposes the wisdom, wit, humor, and reflections of Everyday People, or rich lives outside of the perimeter of celebrity. The faces and voices of people encountered daily are, in effect, introductions to stories of lives and communities far too often hidden from social consciousness. The twentieth century saw a dramatic ascension of African American stories in both fiction and nonfiction to a prominent place in literature and historical inquiry. This change continues, with increasingly more complex and nuanced representations of Black lives. Contemporary representations of blackness frequently emphasize the intersection of race with multiple identities and social positionssuch as, socioeconomic class, ethnicity, gender, geography, and sexuality.

On the Beat of Truth is the product of my mothers more than twenty-year sojourn into peoples history: critically reflecting on her own childhood and adolescent experiences, documenting the memories of Grandma Thomasina, Aunt Mary Babe Minor, and other family members. This book provides a glimpse into the cultural world of the Black Deaf community and adds to a growing literature underscoring the intersection of race, deafness, and, by extension, other identities. Blackness and Deafness were inseparable facets of being for Herbert and Thomasina, and so to, the network of Black Deaf people and institutions that helped sustain them and our family. Grounded in one of the greatest movements of humanity en masse The Great Migrationthe family story told here highlights multiple responses to the violence and oppression of American racial apartheid. Just as the Works Progress Administration interviews of those who lived through enslavement were sparked by an awareness of the necessity to record living memories of American slavery, this work answers a kindred and urgent call to document the testimony of folk whose lives were shaped by the quest for community and dignity in the midst of Jim Crows persistent assault on their humanityin both the rural south and northern city.

Deafness, Blackness, gender, and poverty all converge as factors that drive migration patterns and hardship faced by the Brown and Childress families as detailed in this account. Some dimensions of this memoir invoke ever-constant themes in the twentieth-century African American experience: flight from impending racial violence, the magnet of economic opportunity, the persistence of racial oppression in the North and the power of Black institution-building in midst of urban segregation. Nevertheless, access to deaf education and employment options (considering their deafness) were also push-and-pull forces affecting Thomasina and Herberts respective choices and decisions in their movements from the Carolinas and Tennessee, to the metropolitan Washington, D.C., area. In the District, Herbert and Thomasina were heavily involved in clubs and organizations for the Black Deaf community. In some cases these were spaces within institutional pillars of the Black public sphere; such as the deaf worship service of the Shiloh Baptist Church, whereas in other instances they were autonomous social clubs established by and for the Black Deaf community specifically.

Migrations and the rapid growth of Black urban communities in the twentieth century added new dimensions to African American vernacular style and forms of expression, especially in spoken language. In keeping with this trend, the Black American Sign Language (BASL), which shares some operative principles with American Sign Language (ASL) but has its own particular deep structure and syntax, developed. Racially separate neighborhoods along with the segregation of schools for the deaf facilitated the rise of BASL. Both Thomasina and Herbert attended Black deaf institutions and were grounded in both African American communicative form as well as ASL. Furthermore, On the Beat of Truth provides a snapshot of processes through which families produced their own signs. Illustrating the workwear of tough agrarian labor, Thomasinas sign for her father, Clarence Grindaddy Brown, is synonymous with that of a pair of overallscharacterized by the up and down movements of the thumb and index fingers over the torso, as if detailing a pair of suspenders.

Though a representation of toil was associated with my great-grandfather, Black women in this memoir stand out squarely facing layers of racist, sexist, and economic oppression in both the countryside and city. Many of the day-to-day struggles as remembered by my mother are confrontations with sexism and patriarchy: specifically, in the workplace and, painfully, at home. Indeed, much of the story is driven by my mothers attempt to understand the problematic changes in her fathers behavior and treatment of his family. She locates a definitive source of his anger in a specific act of injustice. While this is likely not the sole explanation for his travail, moms account adds a layer of understanding to the circumstance of being a Black deaf man determined to be a provider in the midst of poverty, racism, and anti-deaf discrimination.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984.