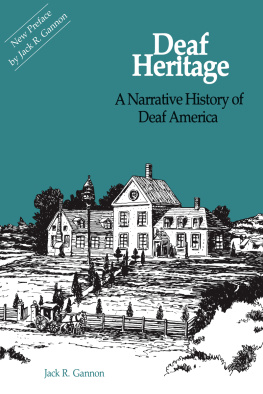

The Stories They Told Me

The Stories They Told Me

The Life of My Deaf Parents

Maria Wallisfurth

Translated by Cornelia Wallisfurth

Gallaudet University Press

Washington, DC

In memory of Peter Jankowsky, a sensitive artist and a friend

Gallaudet University Press

Washington, DC 20002

http://gupress.gallaudet.edu

2017 by Gallaudet University

All rights reserved. Published 2017

Printed in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Wallisfurth, Maria, 1927 author.

Title: The stories they told me : the life of my deaf parents / Maria Wallisfurth ; translated by Cornelia Wallisfurth.

Other titles: Sie hat es mir erzhlt. German

Description: Washington, DC : Gallaudet University Press, [2017]

Identifiers: LCCN 2017004996 | ISBN 9781944838027 (pbk. : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781944838034 (e-book)

Subjects: LCSH: Giefer, Maria, 1897 | DeafGermanyBiography.

Classification: LCC HV2747.G53 W3413 2017 | DDC 362.4/2092243dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017004996

First published in 1979 in Germany by Verlag Herder under the title Sie hat es mir erzhlt ( She Told Me ).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

Preface

Alexandrine is a beautiful name.

It was the name of my godmother, my fathers mother. As was the custom then in Catholic Rhineland, I should have been named after her. But my parents, Wilhelm and Maria, who were born deaf, found it difficult to say and lipread Alexandrine , and so my father gave me the same name as my mother.

My parents subscribed to a daily paper. Every morning, my father put me on his knee, and in his incomprehensible, but to me so familiar, voice he taught me the letters of the alphabet from the paper. When I started school at the age of six, I was already able to read.

The exceptional situation of my parents, and of myself, caused me to ask early for the why and how. I wanted to know the story of their liveswhere they had been before I was born, and who they had been without me. And, I wanted to write it all down.

I read about deaf-mutes, as deaf people were called in their time. People without speech and hearing have always been seen as strange and mysterious. In so called primitive as well as in advanced cultures they were regarded as condemned by the Gods, as creatures living under the curse of invisible, demonic forces. Sometimes they were killed, but in some cultures, they were revered as beings with magical powers.

In European antiquity, Greek philosophers discussed the phenomenon of deaf-and-dumbness and assumed that a person without hearing could not think. Plato granted deaf people a certain amount of intelligence because they were able to communicate with gestures, but Aristotle decided that people without hearing could not be educated. The Church Fathers of the Christian Middle Ages saw deaf people as monstrosities from Hell. To teach them speech, they thought, was impossible and, worse, presumptuous to divine intention. St. Augustine proclaimed that the deaf-and-dumb from birth can never receive the gift of Faith, as Faith arises from the spoken word, from sermons, from what is heard. When my parents went to school, attendance was not compulsory for deaf children; it did not become so until 1911. Despite this, there were several schools for them around the country. The first school was founded in 1778, in Leipzig, by Samuel Heinicke, who was a strong advocate of the oral method. The school in Aachen opened in the 1830s. Without the help of their teachers, my parents would have remained speechless all their lives. They talked to me in their laboriously acquired speech, which I had no problem understanding. They, in turn, read from my lips what I told them soundlessly, while also reading my signs and facial expressions. We always signed and spoke with each other. My parents could never do without these.

I grew up among deaf people because my parents had deaf siblings and many deaf friends. They were part of my family; I felt at home among them, but also lonely. I found release and happiness in reading and writing, in the great gift of language.

Again and again I pleaded with my mother. Mama, please, you tell me about your life! I want to write down! I placed paper and pencil in her reach, so that she could jot down bits of memories as they came to her. Initially, she was reluctant. Why write down? For whom? she would tell me. I poor, deaf-and-dumb, Papa too. People not interested! The notebooks and readers from her years at the Institute for the Deaf in the town of Aachen, which she had kept diligently over the years, now turned out to be of great help in my undertaking.

I also asked my father to tell me about his childhood and adolescent years. How had they lived without me, without the daughter who, from early on, had been their interpreter? My parents would be amazed today if they could see with how much interest my readers follow the story of their lives!

Over the years, they did tell me about their lives, and I have written their stories here, in the way that they told me. Direct quotes are transcribed in the language they used; in other words, the way they signed to me. For this reason, the translations may not appear to be grammatically correct, though they are if one saw them signed.

Finally, I would like to express my heartfelt thanks, my respect, and admiration to all the teachers of the deaf for their demanding and invaluable work.

Maria Wallisfurth, Aachen 2017

Near the young Ahr River, near the source, in the village of Freilingen, Maria Giefer was born on the fourth day of August in 1897. Freilingen, near Blankenheim, belonged to the district of Schleiden, the poorhouse of Prussia. The village is situated on a rise with a view all around of the forests and peaceful valleys of the Eifel mountain range with its extinct volcanoes the Hohe Acht, the Nrburg, the Aremberg, and the Michelsberg. The house she was born in is made from solid stone taken from the Freilingen Castle just across the road. The castle, an impressive structure with two corner towers, had been torn down around 1830.

Marias parents kept a black trunk with iron fittings in their bedroom, on which was written in block letters,

HUBERT GIEFER FREILINGEN KR. SCHLEIDEN REG. AACHEN RHEINLAND PREUSSEN-STEINBCHEL & BRO. INSURANCE LAND LOAN STEAMSHIP LINE AGENTS WICHITA KANSAS

In 1893, when the best wine of the century was ripening on the banks of the Moselle River, the Eifel was suffering famine due to a drought and a bad harvest. Hubert Giefer, Marias father, decided to leave impoverished Freilingen for America to become a rich farmer. He worked as a farm laborer in the endless wheat fields of Kansas and Michigan. For three summers, he saw only yellow stalks reaching to all horizons. Hubert earned money and saved it so he could progress in the new land. He saw where his future lay. But he could not forget Elisabeth, his sweetheart back home in the Eifel. So he returned to take her with him back to America.

But Elisabeths parents would not allow their daughter to move to a strange land. So far away from the villagesomewhere beyond a vast ocean! Hubert had to make a choice: Elisabeth or America, and he decided to stay. He married Elisabeth and they lived on his mothers farm. Elisabeth soon bore two daughters, Maria and Gertrud. He never forgot his dream of a wheat farm of his own in America. It only slumbered.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).