Stubbs - Fear of Music: Why People Get Rothko But Dont Get Stockhausen

Here you can read online Stubbs - Fear of Music: Why People Get Rothko But Dont Get Stockhausen full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: Winchester, year: 2018, publisher: John Hunt Publishing, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Fear of Music: Why People Get Rothko But Dont Get Stockhausen

- Author:

- Publisher:John Hunt Publishing

- Genre:

- Year:2018

- City:Winchester

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Fear of Music: Why People Get Rothko But Dont Get Stockhausen: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Fear of Music: Why People Get Rothko But Dont Get Stockhausen" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Stubbs: author's other books

Who wrote Fear of Music: Why People Get Rothko But Dont Get Stockhausen? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Fear of Music: Why People Get Rothko But Dont Get Stockhausen — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Fear of Music: Why People Get Rothko But Dont Get Stockhausen" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

First published by Zero Books, 2009

Reprinted, 2011

Zero Books is an imprint of John Hunt Publishing Ltd., No. 3 East St., Alresford,

Hampshire SO24 9EE, UK

www.o-books.com

For distributor details and how to order please visit the Ordering section on our website.

Text copyright: David Stubbs 2009

ISBN: 978 1 84694 179 5

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in critical articles or reviews, no part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without prior written permission from the publishers.

The rights of David Stubbs as author have been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Design: Stuart Davies

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY, UK

We operate a distinctive and ethical publishing philosophy in all areas of our business, from our global network of authors to production and worldwide distribution.

The idea which, in turn, formed the basis for this book came to me while I was watching, for perhaps the dozenth time, the Tony Hancock film The Rebel. Hes being escorted around the palatial mansion of a wealthy French artist when he glances up at a piece of abstract expressionist art and exclaims, Whos gone raving mad here, then?

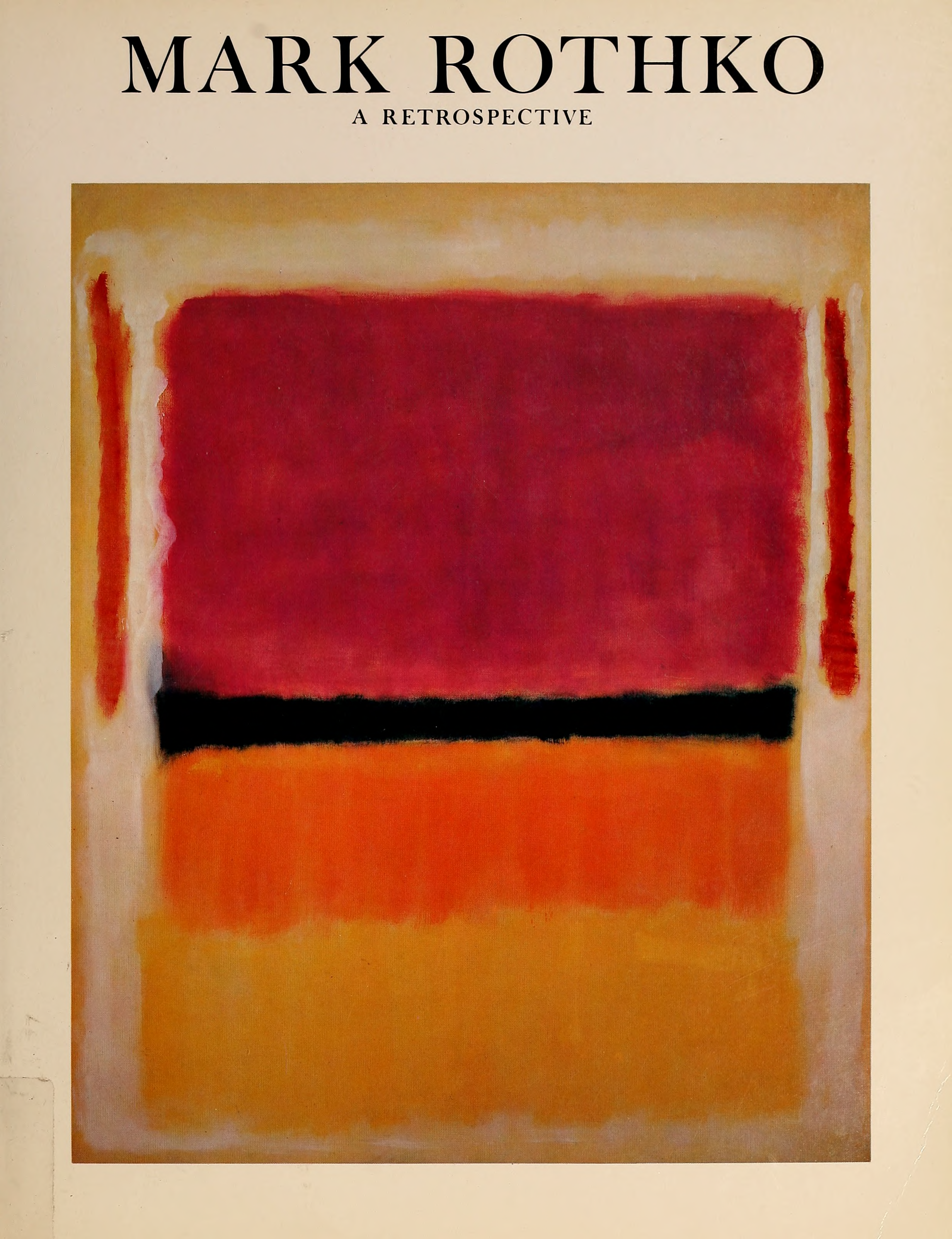

There are chortles all around, for although this film was released in 1961, it was understood even then that people of taste did not make such silly, Philistine remarks. It was understood that this piece of art was the product of rational meditation on the part of the artist, then duly submitted to an apparatus of critical approval, physical and cultural framing, exhibition and dealership, before being laid to rest, hung high on a wall, an elevated watermark of progressive, civilised thinking. Raving mad? Dont be a fool.

It then occurred to me how often the word madness is lazily invoked when those fully aware of the Pollocks and Rothkos of this world encounter by chance the works of experimental and avant garde musicians, of whose activities they are only dimly aware. This happens to me all the time, among good and educated friends and acquaintances of mine its perfectly socially acceptable behaviour. Why has avant garde music failed to attain the audience, the cachet, the legitimacy of its visual equivalent?

There are a number of reasons for this which I shall go on to explore, but its the madness thing that sticks in my own craw. Although some experimental music involves dalliances with irrationalism and the occult, I would prefer to highlight the overwhelmingly rational and coherent reasons why a number of people have chosen to make, and to listen to music which to uninitiated ears sounds cacophonous, atonal - just noise. Some of this music has been accepted as legitimate, some of it remains beyond the pale. The people who make it, however, are in general perfectly willing and able to articulate just what it is they are trying to do and why they are doing it, rarely shuffling off and taking refuge in the sort of mumbled excuses about the music speaking for itself, to which their pop contemporaries are more wont. Part of this book, therefore, is a history, albeit a potted and highly subjective one, of 20th-century music set in its social and aesthetic context and in parallel with developments in the arts. This music happened for reasons.

Ive also resented the somewhat feebly lobbed brickbats of derision which avant garde music and its followers have perennially to endure. As a sometime comedy writer, the simplistic and persistent equation between a love of Stockhausen and chronic humourlessness is wearily offensive. So, every now and again, here and there, Ive tried turning the gun carriage around on the mockers. The ones, who, like Anthony Aloysius Hancock, still dont get it, this late on, and whose own ideas of art appreciation are often based on discredited foundations.

This text isnt intended as a sealed and finished piece of academic work its as much a matter of questions, suspicions and impressions as answers, historical facts and conclusions. Its intended to tease and provoke further reflection, debate and disagreement rather than to settle any matter. It cannot do justice to the massive amount of 21st-century activity, in both art and music, which would merit inclusion in this volume if space did not forbid. That is for another day, perhaps, in another, more expanded text.

Im indebted to the following for inspiration, conversation, interviews and e-mail exchange. David Toop, Dan Fox, Clive Bell, Rob Young, Anne Hilde Neset, Tony Herrington, Chris Bohn, Mark Fisher, Derek Walmsley and all the good people at The Wire magazine, Peter Rehberg, Christoph Cox, Simon Reynolds, Brian Duffy, Gurbir Thethy, Richard Beaudoin, Alex Ross, The Juneau Project, Throbbing Gristle.

October 2007. The Tate Modern, London. Doris Salcedos Shibboleth is on exhibition in the sloping, forbiddingly cavernous Turbine Hall. The Shibboleth consists of what appears to be a long, zig-zagging crack running through the floor of the hall, which grows from barely more than a scratch in the tiling at the halls entrance, to a much larger fissure, like a miniature canyon, some 30 or 40 metres wide at the point where most visitors congregate. As you enter the hall, attendants press leaflets into your hand reading Warning: Please watch your step in the Turbine Hall. Please keep your children under supervision. Come the end of the year and 19 lawsuits have been brought against the Tate Modern by visitors claiming to have been injured by this exhibit.

Today, however, nobody looks at all put out by the schism in the floor. The Tate Modern, very probably the UKs leading tourist destination, is packed, with practically every demographic, every continent, represented. Do a 360 degree swivel and they are all there. In the cafe seats overlooking the Turbine Hall, a pensioner munches diffidently on a damp sandwich. Slumped against the far wall are a couple of down and outs, clutching warm tins of lager, taking in the human traffic. To and fro pass old Americans, young Europeans, huddles of women, single men, families with infants in buggies, retired couples, foreign students, and excited school kids. One tourist and his wife dutifully read aloud in monotone the notes to Shibboleth in the leaflet forced on them, as if reading an instruction manual. Walking down Salcedos incised lineparticularly if you know about her previous work, might well prompt a broader consideration of powers divisive operations as encoded in the brutal narratives of colonialism, their unhappy aftermaths in post-colonial nations, and in the stand-off between rich and poor, northern and southern hemispheres.

Now, here I observe an altogether different schism between the notes and the reality out on the floor. People are enjoying Salcedos exhibit, enjoying it thoroughly. They marvel aloud at the technical aspects, revere the leap of creative imagination it took to conceive of such a thing, such a breach beneath their very feet. They stand astride the schism and snap each other on their mobile phones and digital cameras. They stick their hands down the schism. Since the work of art in this particular case isnt a solid object but an absence of solid object, is that schism, that bit of fresh air theyve just stuck their hands in, the work of art? Are they, therefore, in technical, naughty breach of the Do Not Touch rule, that invisible force field which still surrounds gallery art?

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Fear of Music: Why People Get Rothko But Dont Get Stockhausen»

Look at similar books to Fear of Music: Why People Get Rothko But Dont Get Stockhausen. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Fear of Music: Why People Get Rothko But Dont Get Stockhausen and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.