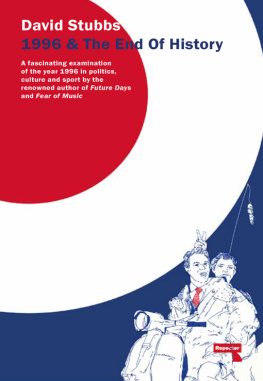

David Stubbs - 1996 and the End of History

Here you can read online David Stubbs - 1996 and the End of History full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2016, publisher: Repeater, genre: History. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:1996 and the End of History

- Author:

- Publisher:Repeater

- Genre:

- Year:2016

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

1996 and the End of History: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "1996 and the End of History" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

1996 and the End of History — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "1996 and the End of History" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

1996 and the End of History

1996 and the End of History

David Stubbs

Preface

Why 1996? Why not 1995, the year in which Britpop, that zenith of national consciousness, blazed hardest with the Blur/ Oasis wars, perhaps the last moment of blue sky mania in UK popular music before the lengthy twilight in whose ever-fading light were still living today? Why not 1997, the year Tony Blair entered Number 10 and Diana exited this world, political and constitutional events whose emotional extremes hadnt been seen in Britain since VE Day?

Because 1996 represented the 1990s at their ripest. I should immediately explain that this 1990s of which I speak is from a UK perspective. In Britain in the late 20th century, specific years, not to mention decades, had an identity in a way you suspected they didnt in less pop-oriented countries such as, say, France or Italy, except insofar as the UK helped provide them as part of the global Anglo-American pop hegemony. This was the premise on which the highly popular I Love series, co-created by Stuart Maconie, was based, in which an array of pundits and celebrity guests would reminisce about a given year. Say 1973 or 1987, and for people of a certain age a bundle of associated memories would blossom instantly like a magicians trick bouquet: memories drawn from sports, TV, pop music, politics, cinema, and fashion all of which seem conflated. The UK is both a leading producer and a passive consumer when it comes to the society of the spectacle. For many of us, our sense of self has been bound up not just with who we vote for and where we come from, but with the things we watch, listen to, wear, with the things that temporarily take us into the dialectical to and fro of pop culture. We dominate, but are easily dominated; we overbear in the habit of passivity we bestow on the world.

1995 may have been the year that Britpop burst through, but 1996 was the year in which it loomed largest and was most overbearing, Oasis in particular, despite not releasing an album that year. 1996 was still a year of Conservative government, but so commanding was Tony Blairs lead in the polls it was clear he was Prime Minister elect. It was possible, in 1996, for him to bask in the unspoiled glow of his triumph in bringing the long Tory nightmare to an end, untarnished by the many compromised decisions he would make almost immediately on taking office in 1997, beginning by accepting a 1 million donation from Formula 1 supremo Bernie Ecclestone, only months later to grant exemption to the motor racing organisation from a general ban on cigarette advertising. All of that was to come; in 1996, he was still practically an honorary Oasis band member.

1996 was also the year of Euro 96, in which English footballing hopes were bound up with the worlds of both comedy and music. It wasnt just Baddiel and Skinners collaboration with The Lightning Seeds, Three Lions, but the sanguine, laddish, retrograde mood engendered by Britpop and Loaded. It wasnt just football that was coming home, but the general sense that after the dark Seventies and the fragmented Eighties, Britain (led by England, of course) had rediscovered its mojo, the spring in its step, the spirit of Hurst and McCartney, the white heat of a bygone era.

1996, in other words, was the year in which cultural forces gathered, as if in a manifestation of the collective unconscious, to recreate the year 1966, before the slide into hippie decadence and misplaced idealism really began.

This book seeks to recapture the inebriated euphoria of that year, and the assumptions that underpinned it: that Britain had been permanently relieved of the seemingly chronic condition of postwar anxiety by the collapse of the Berlin Wall and the End of History; that with the wall had collapsed all of the old rigid, bipolar assumptions about the left and right. Blair would lead us into a happy, central, sunlit upland of post-political inclusivity in which there was no need to storm the gates of the Winter Palace because they were open anyway, free for us to come in and have a look around. The revolution of the late Nineties was that there was no longer any need to think in outmoded, revolutionary terms. These were modernised times in which it was unnecessary to dismantle the old order, for it had developed a human, caring face, encapsulated by Princess Diana; meanwhile, working lads from Manchester were the New Aristocracy. Flashing forward to our own times, in which we find ourselves victims of stealthy deregulation from successive neoliberal governments, its clear that a little more sober analysis of the underlying trends, and a little less inebriated feeling about the something in the air, might have saved us from our present pass.

The 1990s, as they had become by 1996, were antithetical to the 1980s; there was none of that opposition and fragmentation, earnestness and agitation. We were all together, cheering to the same tunes. The struggles of identity politics were over; yes, gays, yes, black people, yes, Asians, yes, strong women, but now all that was established could we not get back to the cheery, white heteronormative consensus of old, before everyone got so uptight?

This book will marvel at the decline in political consciousness that had taken place by 1996, at that post-feminist, post-leftist, anti-futurist hiatus; it will also marvel, in brief flashes, at the decline in my own consciousness in those times. I appear occasionally, like a Guildenstern, in this account: a very minor player indeed. As a staff writer at Melody Maker, I was close to the pop times, even if at a slight, disdainful remove. I interviewed many of the bands of the day, played football with Damon Albarn, as well as spitting numerous little counter-polemics against Britpop. I organised Melody Maker s seventieth anniversary celebrations. However, I had a strange 1996. It began with what was in retrospect probably a nervous breakdown, prompted by a noisy neighbour. But the deeper cause was, I suspect, to do with a feeling that the Nineties hadnt delivered for me the way the Eighties had; I was stranded on a plateau and hadnt ascended to the sort of next level as a writer that would have earned me a detached house somewhere. Instead, I had to share a wall, with the dull thud of mediocre funk-metal pounding tauntingly through at unpredictable hours. Not that I really did anything to entitle me to a breakthrough. I had sitcom ideas, but they were justly rejected. I should probably have done more to earn my keep than pen a weekly satirical column, including such features as Mr Agreeable and The Diary Of A Manic Street Preachers Fan. Instead, I spent many hours at a pub in Waterloo, frequented by Rhys Ifans and a bunch of occasionally rowdy stagehands from the National Theatre on the South Bank. Robbie Williams once came in, for some reason; he was friendly enough but spent an inordinate amount of time reminiscing about a free crate of champagne hed received.

I was alienated from 1996, and yet very much drifting in its swim. Lager, lager, lager, yes. Tony Blair, yes. Even Oasis, up to a point, early on. Going to huge gigs and chanting along to choruses, no. Laddism, oh, no. Three Lions and Euro 96, yes. I read PJ ORourke and felt that a new, progressive, post-leftist politics of some sort was required. What shape that form of politics would take would need some working out, though New Labour were a step in the right direction, probably; meanwhile, there was plenty of time for another drink.

This book, then, is something of a confession, as well as an indictment of the times. Why didnt I do more? Why didnt I do better? Why didnt we do better with the chance we apparently had?

1 Introduction

Identifying eras, epochs, and generations in terms of decades is a pat and popular form of historical shorthand, and, of course, never scrupulously accurate although sometimes not as arbitrary as one might fear. The Fifties were cleaved in two by rocknroll the early Fifties were austere, a period of disgruntlement with the pull-together spirit that enabled the creation of the welfare state, the second half the beginning of a lengthy, reactionary period of Tory rule and supposed never had it so good prosperity. Paradoxically, this second period also saw the conspicuous decline of the old English order, as signified by Edens forced capitulation over the Suez crisis. The Sixties, as Larkin observed, commenced in 1963 with the invention of sexual intercourse and the first Beat-les LP. The decade was again cleaved midway in: a transition from stylish, swinging, prosperous innocence to hirsute, violent, disaffected experience, monochrome to Technicolor, marked by the Beatles passage from

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «1996 and the End of History»

Look at similar books to 1996 and the End of History. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book 1996 and the End of History and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.