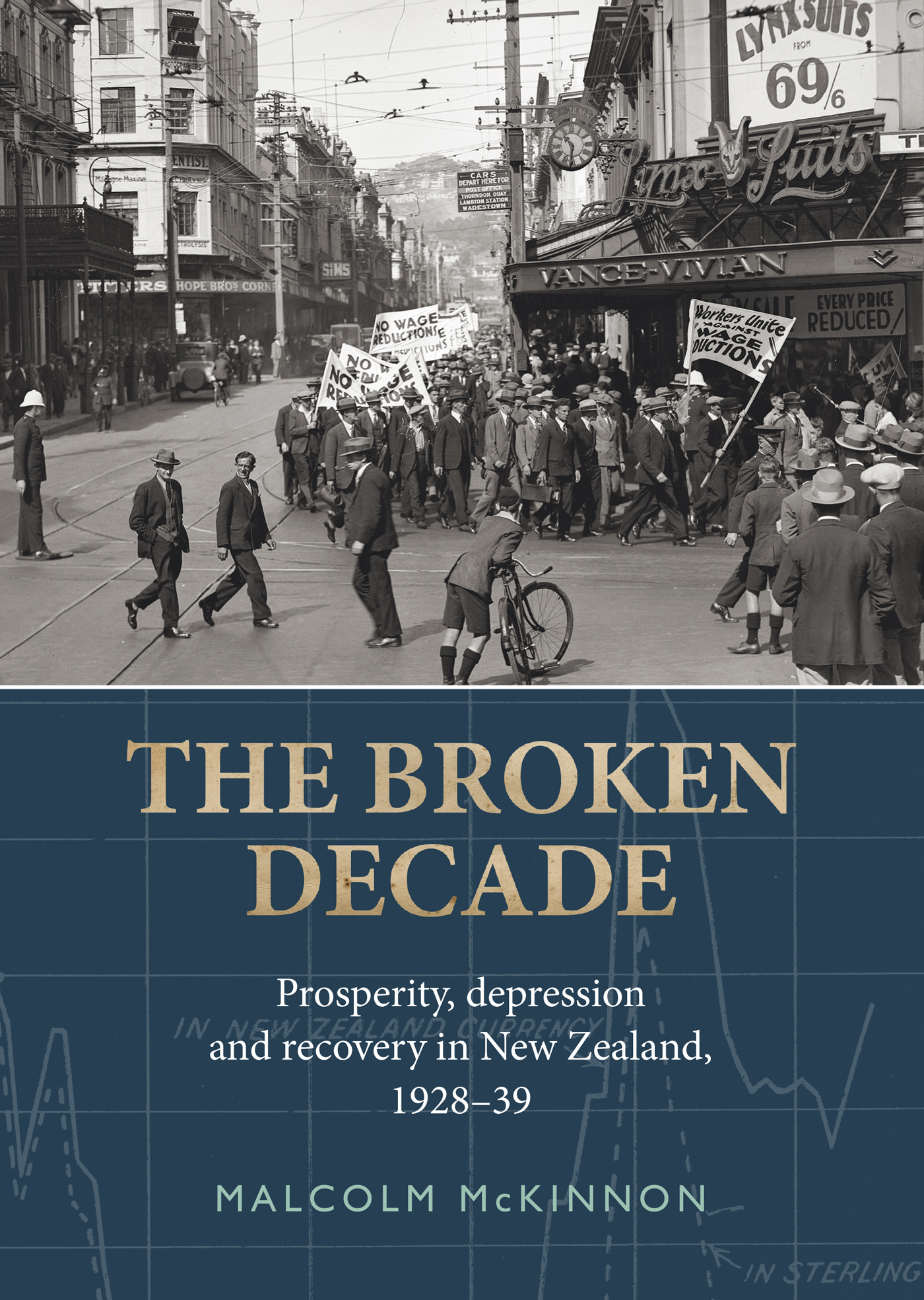

Published by Otago University Press

Level 1, 398 Cumberland Street

Dunedin, New Zealand

university.press@otago.ac.nz

www.otago.ac.nz/press

First published 2016

Copyright Malcolm McKinnon

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

ISBN 978-1-927322-26-0 (print)

ISBN 978-1-98-853163-2 (EPUB)

ISBN 978-1-98-853164-9 (Kindle)

The author was a grateful recipient of a CLNZ Writers Award in 2011

Published with the assistance of Creative New Zealand

A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of New Zealand. This book is copyright. Except for the purpose of fair review, no part may be stored or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including recording or storage in any information retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. No reproduction may be made, whether by photocopying or by any other means, unless a licence has been obtained from the publisher.

Editor: Jane Connor

Design/layout: Fiona Moffat

Index: Robin Briggs

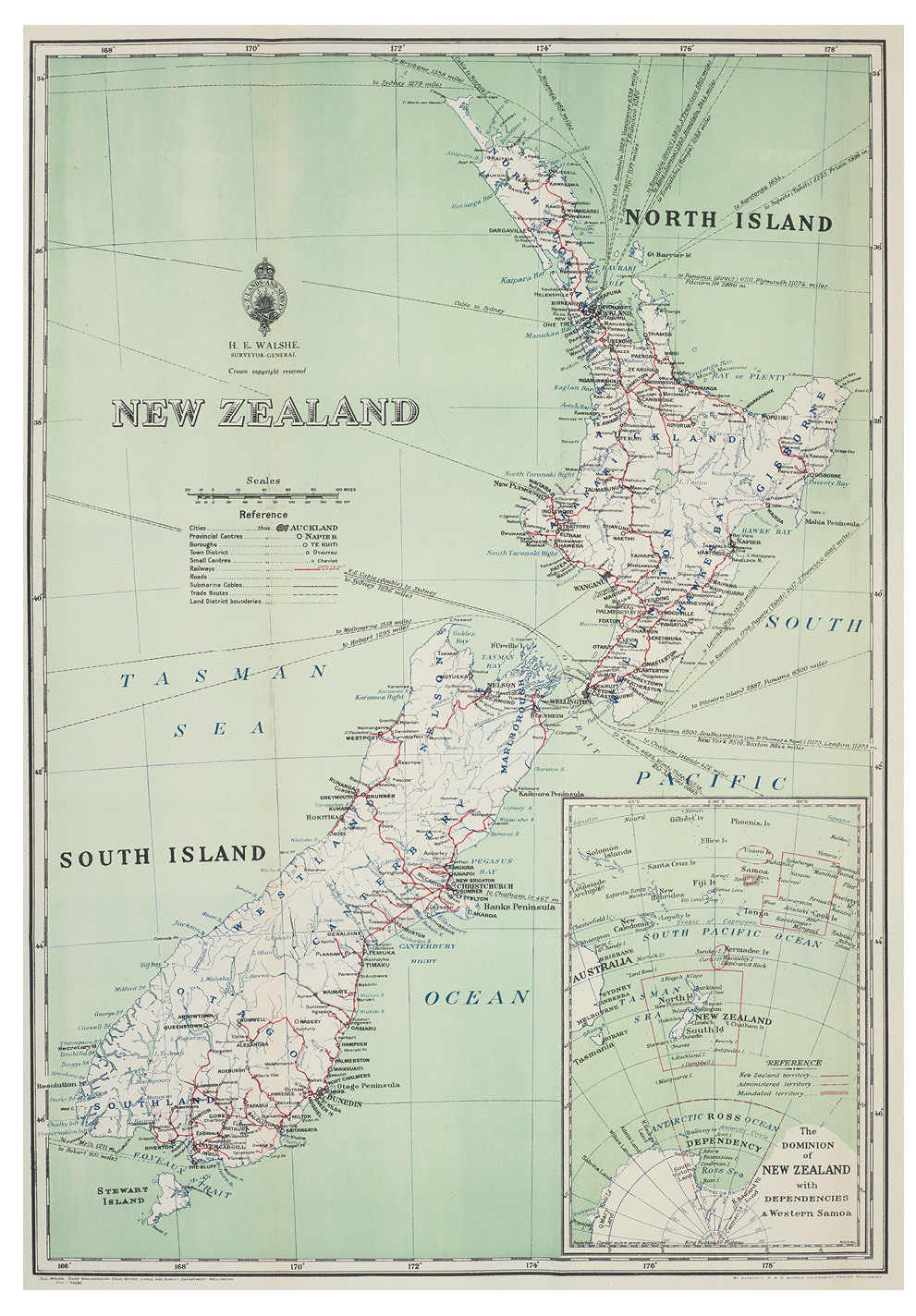

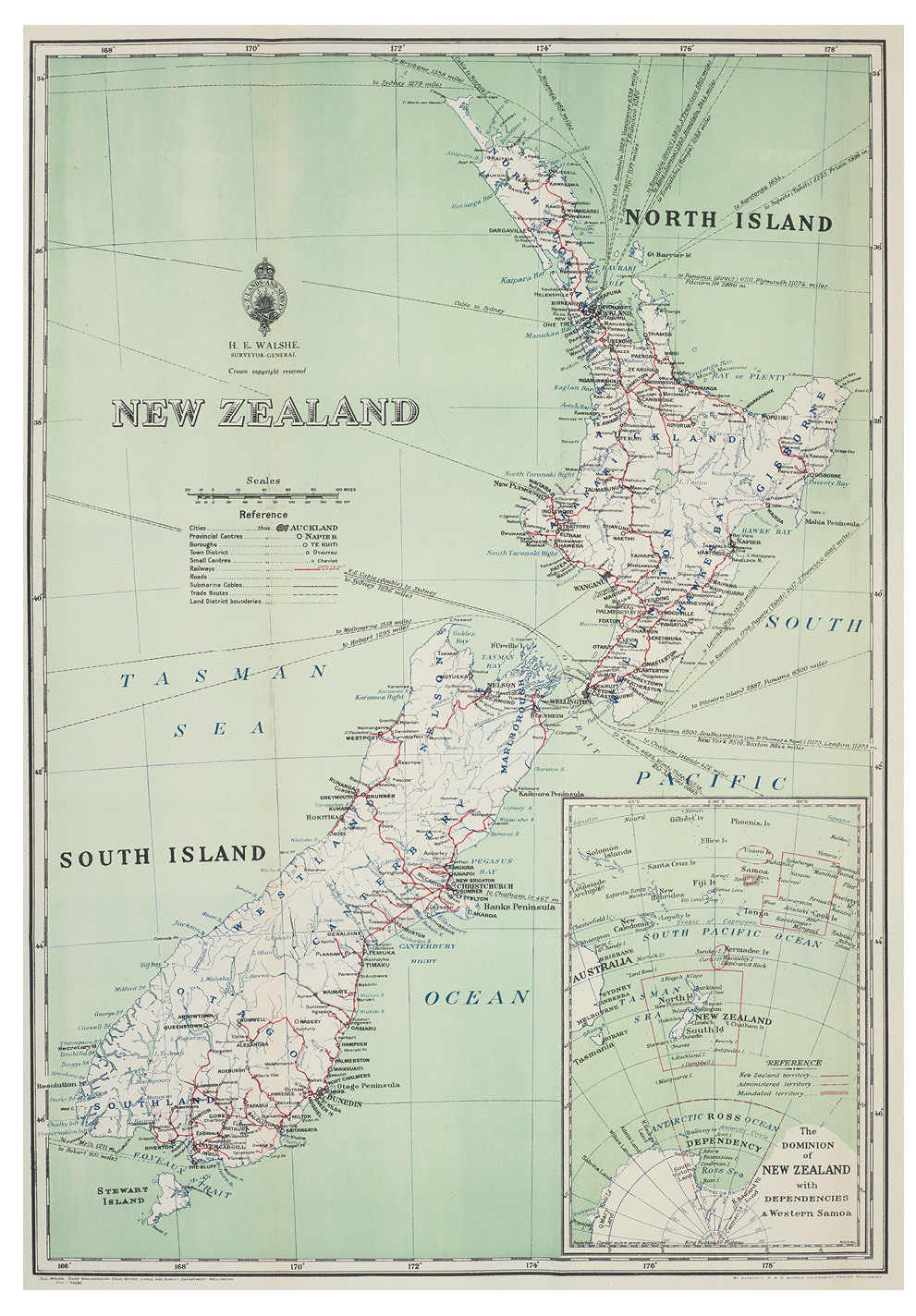

Frontispiece: Endpaper map, New Zealand Official Yearbook 1931, Archive Paper Copy, ATL, Wellington.

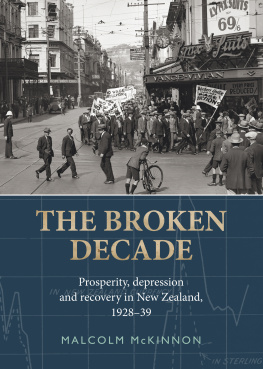

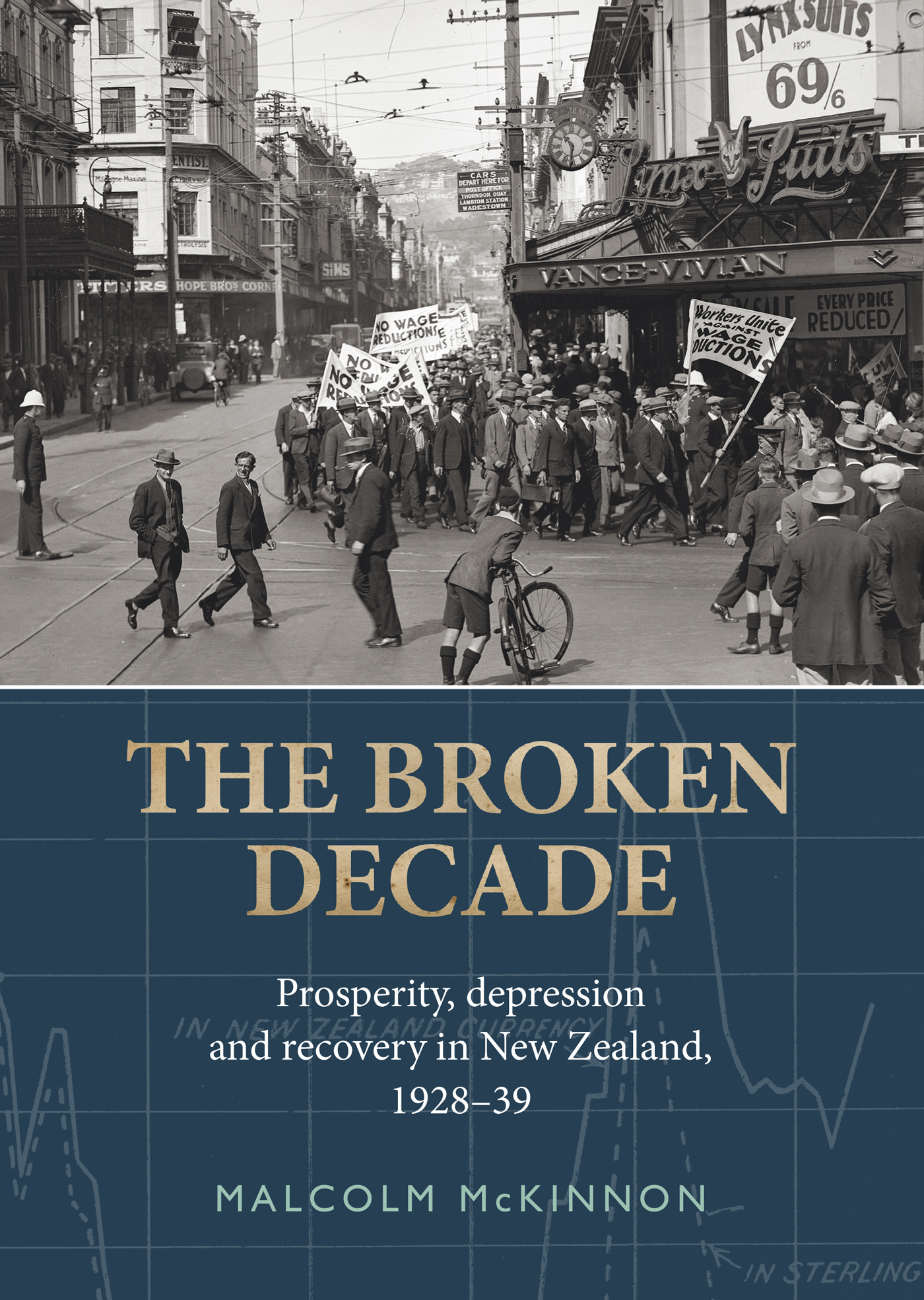

Front cover photograph: A march in Wellington protesting against wage cuts turning from Cuba Street into Manners Street (probably March 1931). 1/2-084837-G, ATL, Wellington.

Author photograph: Keith McEwing

Ebook conversion 2019 by meBooks

CONTENTS

T his book is a narrative and an analytical history of the Depression of the 1930s in New Zealand, one focused on, although not exclusively devoted to, the politics of the period. This approach and focus are choices that merit some explanation.

The Depression is usually regarded as an event, and of course in a sense it was, but an event that lasts five years or more carries many smaller events within it. If we generalise that an event occurred in the Depression, we forgo insights into how the experience of the Depression changed over time and how contemporary understandings of it also altered. In this study the narrative element is foregrounded in the subtitle the words prosperity and recovery conjure up different associations and reactions from Depression. The narrative of this book attempts to capture differences in mood and approach through successive years.

If it would not have overburdened the title, the phrase political response could also have been added to indicate the nature of the analysis that shapes the narrative. How did the Depression play out politically? What range of interests and lobbies contested for influence and power through these years and how were those contests characterised?

The focus on politics provided a useful limiting device. Historians habitually resort to more work to be done to justify omissions, but the political focus also enabled the book to be kept to a realistic length. That said, the text and the images both venture beyond the political realm to capture the experiences of ordinary people through the Depression. They also at times take us beyond the Depression. Not all life in the early 1930s fits a Depression frame of reference. Indeed, there is probably a book to be written on how the notions depression and the 1930s sit alongside each other then and now.

Many debts have been accumulated in the course of researching and writing this book, which it is a pleasure to acknowledge. Both Copyright Licensing Ltd and the History Research Trust Fund of Manat Taonga provided indispensable financial assistance. I am deeply indebted to a variety of scholars who read through the whole or a large part of the manuscript and provided cogent comments and suggestions. Ones own progeny are never regarded quite so affectionately by others and to read and comment on someone elses manuscript, however innately interested you are in the subject and however much goodwill you possess towards the author, is a true test of collegiality and friendship. My biggest debt in this respect is to Erik Olssen, who read the manuscript when it was a lumbering beast and made compelling suggestions for restructuring and focusing. Foremost among the other readers, he is excused any responsibility for the deficiencies that remain.

Simon Boyce, Matthew Cunningham, Brian Easton, Gary Hawke, Jim McAloon and Redmer Yska, all of whom have probed different facets of the period, were very helpful and generous with their time and feedback. Other scholars and students of the period who provided welcome suggestions and/or feedback were Ann Beaglehole, James Bennett, Michael Bassett, Michael Biggs, Michael Brown, Paul Callister, Ross Carter, Karen Cheer, David Colquhoun, Peter Cooke, Anthony Dreaver, David Grant, Richard Hill, Kate Hunter, Harshan Kumarasingham, Cyble Locke, John E. Martin, Charlotte Macdonald, Simon Nathan, Melanie Nolan, Phil Parkinson, Jock Phillips, Kirsty Ross, Ben Schrader, Oliver Sutherland, Kerry Taylor, Bob Tristram, Jim Urry, David Verran, James Watson, John Weaver, the team at History Works, the late Tim Beaglehole and the late Bill Renwick. Sam Elworthy was a robust and therefore valued interlocutor.

I benefited from the insights of a range of other scholars whose long-since-completed works have remained mines of information and sources of intellectual stimulation; I am thinking particularly (but not exclusively) of theses by Robin Clifton, Lucy Marsden, P.G. Morris, Rosslyn Noonan, J.R. Powell, Michael Pugh, A.J.S. Reid, Ross Robertson and James Watson. In a special category is Tony Simpson and The Sugarbag Years, the latter the study that more than any other is cited by contemporary New Zealanders when the Depression of the 1930s is mentioned. This book does not replace that work; it is more in the nature of a conversation with it.

A study like this necessarily involves research in archives and records in a variety of depositories, and I am indebted to the expert, able and helpful individuals who staff them. I am grateful to the Alexander Turnbull Library above all, but also to Archives New Zealand (its offices in Wellington, Auckland and Dunedin); the Auckland City Council; the Auckland War Memorial Museum; the Sir George Grey Room at the Auckland Central Library; the University of Auckland Special Collections; the Fletcher Trust Archive; the Gisborne District Council; the Tairawhiti Museum in Gisborne; Puke Ariki Museum in New Plymouth; the Sarjeant Art Gallery/Te Whare o Rehua, Whanganui; Palmerston North Public Library; Te Aratoi, Masterton; the Museum of New Zealand/Te Papa Tongarewa; the Parliamentary Library in Wellington; the Wellington City Council; the J.C. Beaglehole Room at Victoria University of Wellington; the Christchurch City Council; the Canterbury Art Gallery; and the Hocken Collections at the University of Otago.

It is truly now impossible to imagine carrying out this kind of research (and yet in a not too distant past scholars did) without the resources of Papers Past (www.paperspast.natlib.govt.nz) and other digitised sources of records, notably those of the Appendices to the Journals of the House of Representatives, historical New Zealand statutes and the

Next page