Photo credits:

Background: pashabo/shutterstock.com

chapter 1, Harriet Beecher Stowe: Harriet Beecher Stowe/public domain

chapter 1, Lydia Maria Child: Lydia Child/public domain

chapter 2, rangers: White Mountain rangers, ca. 1861/Library of Congress/public domain

chapter 2, Frances Clayton: Frances Clayton/Library of Congress/public domain

chapter 3, Susie Baker King Taylor: Susie King Taylor/public domain

chapter 4, Belle Boyd: Belle Boyd/Library of Congress/public domain

chapter 4, Rose Greenhow and daughter: Rose Greenhow and Daughter/Library of Congress/public domain

chapter 4, Pauline Cushman: Pauline Cushman/Library of Congress/public domain

chapter 4, Harriet Tubman: Harriet Tubman/Library of Congress/public domain

chapter 5, Anna Ella Carroll: Anna Ella Carroll/Maryland Historical Society

chapter 6, Sarah Dawson: Sarah Dawson/public domain

chapter 7, Cornelia Peake McDonald: Cornelia Peake McDonald/public domain

chapter 8, Harriett Jacobs: Harriet Jacobs, ca. 1894/public domain

chapter 9, Mary Ann Shadd Cary: Mary Ann Shadd Cary/public domain

chapter 10, Clara Barton: Clara Barton/public domain

chapter 10, Mary Ann Bickerdyke: Mary Ann Bickerdyke/Library of Congress/public domain

chapter 10, nurse: Two wounded Federal soldiers are cared for by Anne Bell, a nurse during the American Civil War, ca. 18611865/public domain

chapter 11, Mary Walker: Mary Walker/Library of Congress/public domain

chapter 12, Chipeta: Chipeta/Library of Congress/public domain

chapter 12, Maggie and Mary: Mary E. Schwandt Schmidt (Mrs. William) and Snana Good Thunder (Maggie Brass)/Minnesota Historical Society

chapter 13, Sarah and William McEntire: Sarah and William McEntire/family photo courtesy Shauna Gibby

chapter 13, Kady Brownell: Kady Brownell/Library of Congress/public domain

chapter 14, Harriet Tubman: Harriet Tubman/Library of Congress/public domain

chapter 14, Clara Barton: Clara Barton/public domain

chapter 14, Varina Davis: Varina Davis/Portrait by John Wood Dodge, 1849/public domain

During the Victorian era, when photography exposures were painfully long, it was common practice to take photographs of children by placing them on the laps of their mothers, who were completely obscured by a veil. The intent, of course, was to keep a squirmy child calm during the thirty-second-long camera exposure. To modern viewers, these Hidden Mother images appear more than a bit creepy, with the shadowy outline of a woman or a pair of disembodied hands lurking like ghostly imprints behind the infant.

Though they seem rather macabre to viewers today, the photos, on a metaphorical level, are apt representations of a womans role throughout historyall too often she has been relegated to the background, presented as no more than an obscured figure supporting others, unseen for her own merits. Historians, thankfully, are beginning to remove that veil, allowing her to step forward and speak of her own experience in her own wordsturning his-story into their-storybequeathing to us all a truer, fuller, richer version of events.

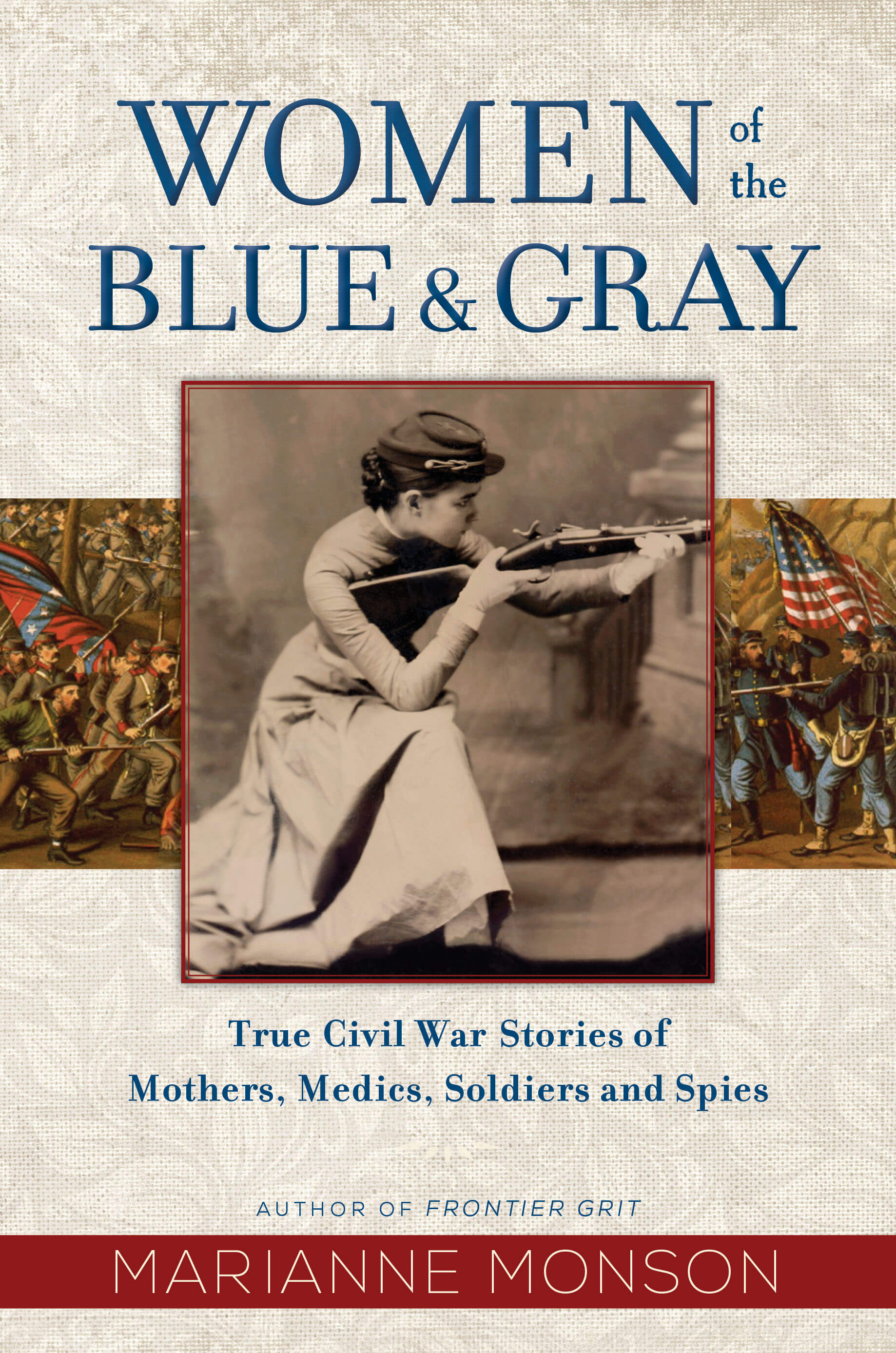

Walk through any Civil War museum of this country, and youll find army uniforms, battle flags, percussion rifles, Colt revolvers, war medals, and photographs of soldiers. Here and there, tucked into corners, you may be lucky enough to find displays featuring a handful of women who contributed to the war effort. You would never guess from looking at such presentations that the vast majority of people impacted by this conflict were not male military leaders but civilians, whose perspectives describe a large part of what this country endured in the long years that stretched between 1861 and 1865.

And yet, behind the objects held within display cases of glass, many stories of women are waiting to be told. This straw hat, worn by a soldier to his death, was crafted by the hands of his sister; that mending kit, carried by another soldier, was cut and sewn from the fabric of his sweethearts dress; the ammunition cartridges on display were rolled by female factory workers. Women designed and created the flags men carried into battle; they braided gold epaulets for uniforms, while black female hands helped pick the cotton that clothed the entire nation. Female nurses cared for soldiers who fell on battlefields, then sent locks of hair and personal items to comfort mourners. Survivors cherished these items and, in many cases, donated the majority of them to museums to preserve their loved ones memories.

But beyond the war stories weve heard most often, women also fought in the war disguised, recorded central events in journals, counselled generals on strategy, worked in factories, engaged in acts of espionage, smuggled medicines across enemy lines, organized, fundraised, and helped finance the war. In post-war years, women cared for the veterans who returned home, buried those who didnt, and listened to male survivors talk about their service. To support these veterans, they held ceremonies, erected monuments, and persuaded legislatures to declare holidays. These dedicated women might have accurately been called business consultants, philanthropists, medical personnel, event coordinators, and psychologists; and in later generations, they would have been properly compensated.

Throughout my research for this book, many people asked me, and some rather anxiously, Are you writing about the War from the perspective of the North or the South? My reply was always, Im telling it from the womens perspectivesNorth, South, black, white, Native American, immigrant, and other. The stories we tell matter, and these need to be told in order to achieve a clearer understanding of the conflict which is, in many ways, at the heart of our identity as a nation.

I believe the anxiety I often sensed was due to the fact that, without a doubt, deep divides remain in this country. The events of the Civil War are intrinsically connected to debates that continue to this day: whether its the presence of the Confederate flag or the removal of Confederate monuments. The intensity of these debates is a tribute to the power of storytelling and its ability to influence the collective knowledge of a nation.

The stories we tell are powerful. And they matter.

If you, like I did, grew up in the North or were raised on the Northern view of the war, you may find yourself growing uncomfortable that the Southern view is allowed room in these pages at all. This is a natural reaction given the fact that during the era of post-Reconstruction, many in the South wielded their view of the conflict and of slavery as a way to justify ongoing racial prejudice in the country. The Lost Cause narrative allowed powerful white males on both sides to reconcile after the war, while erasing many of the initial gains that had been made toward racial equality.

For this reason, there is understandable sensitivity toward anything that smacks of defending the Confederate cause. And yet, from a conflict resolution standpoint, the women of the South simply experienced the war in an entirely different manner than did their sisters in the North. The level of violence, destruction, and loss they endured is unparalleled by the women whose front yards never became a battlefield. The Southern womens stories must be told from the framework of their own perspective, with a few essential departures from the Lost Cause narrativesmost important, of course, being the reintroduction of minority voices to acknowledge the loss, destruction, and violence endured by those who were enslaved.