Drew Gilpin Fauste - Mothers of Invention: Women of the Slaveholding South in the American Civil War

Here you can read online Drew Gilpin Fauste - Mothers of Invention: Women of the Slaveholding South in the American Civil War full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 1996, publisher: The University of North Carolina Press, genre: Science. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Mothers of Invention: Women of the Slaveholding South in the American Civil War

- Author:

- Publisher:The University of North Carolina Press

- Genre:

- Year:1996

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Mothers of Invention: Women of the Slaveholding South in the American Civil War: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Mothers of Invention: Women of the Slaveholding South in the American Civil War" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Drew Gilpin Fauste: author's other books

Who wrote Mothers of Invention: Women of the Slaveholding South in the American Civil War? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Mothers of Invention: Women of the Slaveholding South in the American Civil War — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Mothers of Invention: Women of the Slaveholding South in the American Civil War" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

MOTHERS OF INVENTION

The Fred W. Morrison Series in Southern Studies

COPYRIGHT

1996

The University of North Carolina Press.

All rights reserved.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Mothers of invention: women of the slaveholding South in the American Civil War / by Drew Gilpin Faust.

I. United StatesHistoryCivil War, 1861-1865Women. 2. WomenConfederate States of AmericaHistory.

g73.7'15042-dc20

00 99 98 97

95-8896

CIP

ISBN 0-8078-2255-8 (paper)

DEDICATION

In Memory of

ISABELLA TYSON GILPIN (1894-1983)

CATHARINE GINNA MELLICK (1895-1989)

CATHARINE MELLICK GILPIN (1918-1966)

CONTENTS

: All the Relations of Life

: What Shall We Do?: Women Confront the Crisis

: A World of Femininity: Changed Households and Changing Lives

: Enemies in Our Households: Confederate Women and Slavery

: We Must Go to Work, Too

: We Little Knew: Husbands and Wives

: To Be an Old Maid: Single Women, Courtship, and Desire

: An Imaginary Life: Reading and Writing

: Though Thou Slay Us: Women and Religion

: To Relieve My Bottled Wrath: Confederate Women and Yankee Men

: If I Were Once Released: The Garb of Gender

: Sick and Tired of This Horrid War: Patriotism, Sacrifice, and Self-Interest

: We Shall Never... Be the Same

: The Burden of Southern History Reconsidered

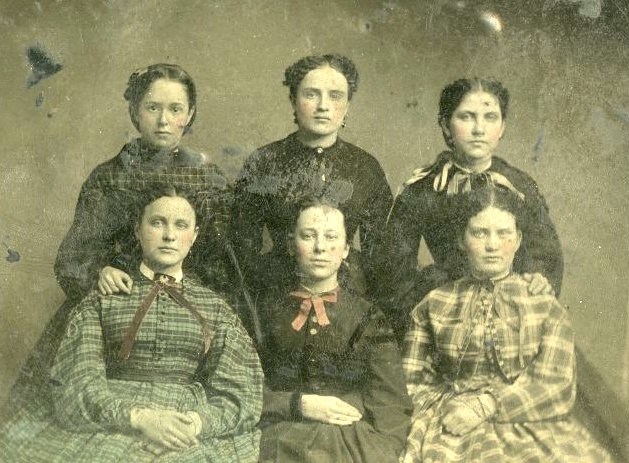

ILLUSTRATIONS

PREFACE

When I was growing up in Virginia in the 1950s and 1960s, my mother taught me that the term "woman" was disrespectful, if not insulting. Adult femalesat least white onesshould be considered and addressed as "ladies." I responded to this instruction by refusing to wear dresses and by joining the 4-H club, not to sew and can like all the other girls, but to raise sheep and cattle with the boys. My mother still insisted on the occasional dress but, to her credit, said not a negative word about my enthusiasm for animal husbandry.

Looking back, I am sure that the origins of this book lie somewhere in that youthful experience and in the continued confrontations with my motheruntil the very eve of her death when I was nineteenabout the requirements of what she usually called "femininity." "It's a man's world, sweetie, and the sooner you learn that the better off you'll be," she warned. I have been luckier than she in that I have lived in a time when my society and culture have supported me in proving that statement wrong.

My professional historical interest in the South grew out of those early years as well, for I lived in Harry Byrd's home county during the era of Brown v. Topeka and "massive resistance" to school desegregation, a time when even a young child could not be unaware of adult talk and worry about social transformations in the offing. It was not until I heard news about the Brown decision on the radio that I even noticed that my elementary school was all white and recognized that this was no accident. But I quickly penned a letter to President Eisenhower to say how illogical I thought this seemed in the face of the precepts of equality I had already imbibed by second grade. I confronted the paradox of being both a southerner and an American at an early age.

That I should become a historian, focus my scholarship on the South and the Civil War, and write a book on white women in the Confederacy seems almost overdetermined. That I should dedicate it to the memory of my mother and my two grandmothers"ladies" who were at the same time the most powerful members of my familyseems entirely fitting. All three were, in fact, women deeply affected by war, though for them the homefront did not merge with battle the way it did for Confederate women. But my grandmothers sent husbands off to Europe in the First World War, and one lost an only brother in a volunteer flying mission over the English Channel. My mother was married in 1942 with less than a week's notice, and my parents were soon separated for eighteen months by my father's service overseas. The formal photographs of my father, uncles, and grandfathers that decorated the shelves and tables of my childhood, pictured them in uniform. I grew up thinking all men were soldiers.

I have tried to write this book as if my mother and grandmothers were going to read it. After two decades as an academic historian, I sometimes fear I no longer can communicate in a manner that will engage a general reader, but the compelling nature and human drama of this war story have made me want to try. As a consequence, the scholarly reader will find most references to theoretical questions and historiographical debates in the endnotes rather than in the text. I have tried not to drown out the Confederate women's voices with my own.

In fact, a considerable portion of my interest in this subject has derived from the richness of language and expression in the voluminous collections of writing elite southern women left as their historical legacy. Because they were educated and because they often had leisure time for reflection, they created an extensive written record of self-justification as well as introspection and self-doubt. Although the history of elites has not been a particularly fashionable topic in recent years, I have been attracted to it by the opportunity to use such abundant and revealing sources to explore how military and social crisis can challenge power and privilege to define their essential nature. For the women as well as the men of the South's master class, the Civil War was indeed, as I am hardly the first to observe, a moment of truth.

The self-consciousness and eloquence of the Confederacy's elite women, preserved in diaries, letters, essays, memoirs, fiction, and poetry, have provided this study with documentation of extraordinary range as well as richness. Diaries written for the author's eyes alone, for her children, or for posterity must of course be interpreted differently from letters addressed to particular individuals, or novels produced within the constraints of popular contemporary genres, or reminiscences composed through a haze of reconstructed memories and changed circumstances. But the variety of material has ultimately worked to enhance my understanding through its diversity of forms and complementarity of perspectives.

Published editions of women's writing from the Civil War era grow more numerous every year and greatly aided me in my task. The most compelling part of my research, however, was my visits to more than two dozen manuscript repositories, concentrated in eleven southern states and the District of Columbia,but including a number of Yankee institutions as well. My debt to all those who assisted me at those libraries and archives is incalculable.

I have listened to the voices of more than 500 Confederate women. But my research extended well beyond the writings of the women themselves, for it was not just females who were worried about the changing nature of identity and of gender relations in the wartime South. White women's self scrutiny engaged them in an ongoing conversation with the larger society of which they were a part, in a process of negotiation about what womanhood would come to mean in circumstances of dramatic social upheaval. As a result, I have directed considerable attention to public discourse about gender and about woman's place in the new southern nation. Some of this discussion I have discovered in Confederate popular culturein plays, novels, songs, and paintings. But I have also found it closely associated with political dimensions of southern lifein remarks by leading southern statesmen such as Jefferson Davis, in newspaper editorials, and even in public policy decisions.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Mothers of Invention: Women of the Slaveholding South in the American Civil War»

Look at similar books to Mothers of Invention: Women of the Slaveholding South in the American Civil War. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Mothers of Invention: Women of the Slaveholding South in the American Civil War and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.