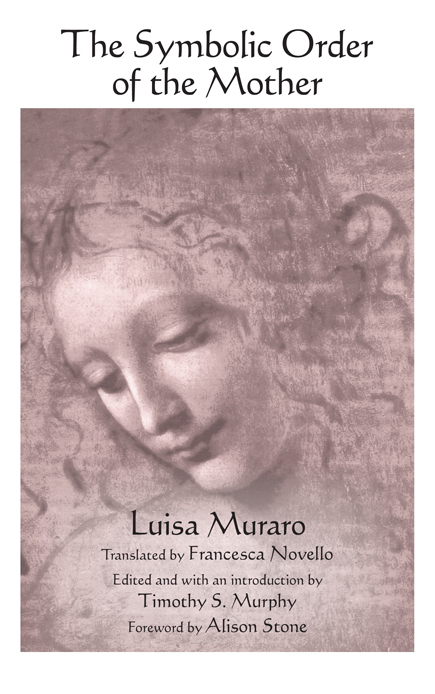

SUNY series in Contemporary Italian Philosophy

Silvia Benso and Brian Schroeder, editors

The Symbolic Order

of the Mother

The Symbolic Order

of the Mother

Luisa Muraro

Translated by

Francesca Novello

Edited and with an Introduction by

Timothy S. Murphy

Foreword by

Alison Stone

Published by State University of New York Press, Albany

2018 State University of New York

1991, 2006 Editori Riuniti, Lordine simbolico della madre

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

For information, contact State University of New York Press, Albany, NY

www.sunypress.edu

Production, Ryan Morris

Marketing, Michael Campochiaro

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Muraro, Luisa, 1940 author. | Murphy, Timothy S., 1964 editor.

Title: The symbolic order of the mother / Luisa Muraro ; translated by Francesca Novello ; edited and with an introduction by Timothy S. Murphy ; foreword by Alison Stone.

Other titles: Ordine simbolico della madre. English

Description: Albany, NY : State University of New York, 2018. | Series: SUNY series in contemporary Italian philosophy | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016059959 (print) | LCCN 2017050116 (ebook) | ISBN 9781438467658 (ebook) | ISBN 9781438467634 (hardcover : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Mothers. | Identity (Psychology)

Classification: LCC HQ759 (ebook) | LCC HQ759 .M92613 2018 (print) | DDC 306.874/3dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016059959

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Contents

Alison Stone

Francesca Novello

Timothy S. Murphy

Foreword

Luisa Muraros book Lordine simbolico della madre was published in 1991 and translated into German in 1993, Spanish in 1994, and French in 2003. The publication of this translation is very welcome; it makes available to English speakers, at last, this important work of Italian feminist philosophya singular and affecting book. It has a personal tone, as Muraro leads us through the development of her own thought. She begins by describing her intellectual difficulties and blockages, the problem of how to begin writing, how even to think. She traces the source of these difficulties in the patriarchal culture and philosophy she has inherited, and she gradually elaborates a solution, in the guise of the symbolic order of the mother.

During this elaboration Muraro draws on a wide range of interlocutors: Irigaray, Kristeva, Hegel, Lacan, and Adrienne Rich among others. As this list indicates, her book speaks to debates about the relations between feminism and psychoanalysis; about the possibilities for a feminism of sexual difference, a project associated particularly but not exclusively with Luce Irigaray; and about motherhood and the maternal. Muraros book may also be read as a contribution to the development of continental feminism, the emerging body of work that lies at the intersection of feminist and continental European philosophy.

Above all, Muraros book is important for its highly original theses regarding the maternal order, theses that have remained little known to Anglophone feminists. So in this foreword I will introduce these theses as I understand them, bearing in mind that there is an open-endedness, and so openness to interpretation, about many of Muraros key terms. This open-endedness is the inevitable result of Muraros attempt to articulate matters that patriarchy has left unthought.

Muraro reminds us that our mothers teach us to speakand often readin childhood. Our mothers introduce us into language, and thus transmit civilisation: mothers teach their children to speak and do many other things that are foundations of human civilization (19). As she insists, Muraro means mothers here literally, not metaphorically. But she also says that she speaks of the mother symbolically, which she explains as follows:

During childhood, we worshipped the mother and all that is related to her, from the husband she had to the shoes she wore, from the sound of her voice to the smell of her skin. We have put her at the center of a magnificent and realistic mythology. I entrust to the little girl I was, to those little girls with whom I grew up, to the little girls and boys who live among us, I entrust to them the task of testifying to the non-metaphorical symbolicity of the mother. (19)

As a symbolic figure, then, the mother is invested by us when we are children with an immense wealth of meaning and emotional import. But those who are so invested are our actual, real, literal mothers. This passage, moreover, exemplifies how Muraro draws on personal experience and recollections and imbues them with philosophical significance, moving seamlessly from fragments of life-history to metaphysicsa quality I greatly admire in her book.

Muraro writes of speech as the medium in which we negotiate our early relationships with our mothers: Language can be given to us only by means of negotiation with the mother because language is nothing other than the fruit of that negotiation (46). These early relationships are bodily and deeply emotional, so that here the body and the word are completely entwined. In these relationships, too, our mothers have authority for us, and to this extent the mother-child relationship is one not of equality but disparity, insofar as the mother is our authority, guide, and teacher.

In advancing these claims Muraro is opposing the many psychoanalytic views, including those of Freud and Lacan, according to which the father or father figure, not the mother, embodies law, language, and civilisation, so that we must all break away psychologically and emotionally from our mothers to enter civilisation and become speaking beings. Kristeva, in this vein, claims that For man and for Muraro agrees with the psychoanalytic tradition, however, on the immense importance of young childrens early relationships with their mothers. For Muraro, our early lives are thoroughly relational: at this time, the subject in relation with the matrix of life is a subject that can be distinguished from the matrix but not from its relation to it. Therefore, it is not exactly a relation between two (38). Thus, for Muraro, in our childhood relationships with our mothers we are held within this matrix of life.

Muraro understands the language into which our mothers initiate us in a particular way, as constituting a symbolic order. That is, language is not a neutral tool of communication; rather, each language embodies a determinate horizon of meanings, which we take on in learning to speak. Indeed, more strongly still, Muraro regards language as the medium through which the world reveals itself to us, becoming manifest in a determinate shape. It is not, then, that language cuts us off from the world as it might really be; instead, language is the condition of the worlds appearing to us and becoming known by us at all. To enter language, and so for the world to present itself to us in a specific way, is to enter the realm of truth, for Muraro: truth as the self-revelation or self-manifestation of the world, which precedes and makes possible truth as correspondence.