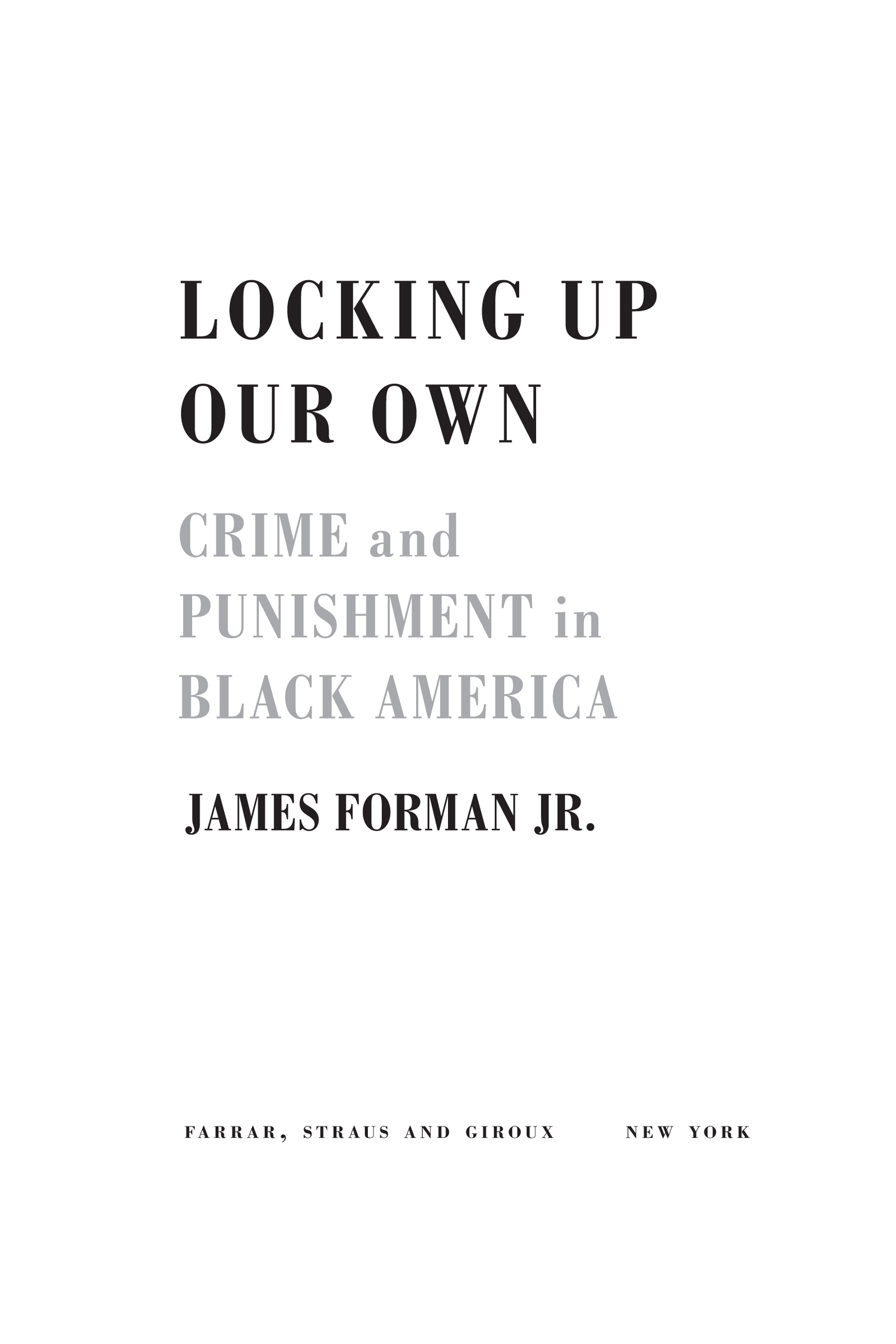

Contents

Guide

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

To Ify and Emeka,

the loves of my life

All of us in the public defenders office feared the Martin Luther King speech. Curtis Walker, an African American Superior Court judge in Washington, D.C., was famous for it. And today Brandon, my fifteen-year-old client, was on the receiving end.

Son, your lawyer here has been telling me some good things about you: how you dote on your little sister, how your football coach says you are a born leader, how some of your teachers believe you can do better. He says he has found a program for you that will help you with school, and that I should give you a chance at that and not lock you up.

Brandon had pleaded guilty to possessing a handgun and a small amount of marijuanaenough to use, but not to sell. I had argued for probation. Judge Walker told Brandon he was considering my proposal. But first he had some things to say.

Mr. Forman says you need another chance. But let me ask you, do you even realize how many chances youve already had? You might think you have it hard. But let me tell you, it was harder once. Black boys picked cotton once upon a time. Sat in the back of the busthose who were lucky enough to even be on the bus, and not walking.

Judge Walker was getting into his rhythm now. He wasnt a preacher, but he sounded like somebody who had spent more than a few Sundays in the pews.

Now you can go to school, study hard, live your dreams. It isnt easyI know that. But it is possible. And people fought, struggled, and died for that possibility. Dr. King died for that, son. And what are you doing? Not studying! No, you are cutting class, runnin and thuggin, not listening to your momma or grandmother. Instead, you want to listen to some hoodlum friends. By now, the judge was glaring at Brandon.

Out of the corner of my eye, I could see that Brandon was keeping his gaze steady on the judge. This was good. Judge Walker liked that. If Brandon avoided eye contact, Judge Walker would think he was being disrespectful.

Well, let me tell you: Dr. King didnt march and die so that you could be a fool, so that you could be out on the street, getting high, carrying a gun, and robbing people. No, young man, that was not his dream. That was not his dream at all.

This was the speech I knew so well. The words changed a bit each time, but the theme stayed the same: Life is not easy for African Americans today, but its better than it was, and you best stop being a thug and start taking advantage of the opportunities that others fought so hard for.

I was also familiar with the emotions etched on Judge Walkers face as he spokeanger, frustration, and despair. I was a new public defender, but the judge had been around for a long time. He looked and sounded like somebody who was tired of lecturing black boys (and a few girls), but not so tired that he wouldnt try one more time. He was mad at Brandon, but he hadnt given up on him. He just seemed like a man with no good alternatives, confronting a problem that was too big for him to solve.

Judge Walker paused, took his eyes from Brandon, and started looking through the case materials spread out before him. His lecture done, he was taking his time imposing a sentence. Another good sign. Judge Walker was known for giving defendants a fair trial, but if you lost, look out. Defense attorneys called him a long-ball hitter, referring to the lengthy sentences he imposed. But now he was hesitating. Maybe I had persuaded him that this was not an easy case.

I knew that probation was a long shot. The gun charge was serious. And worse, a report from the courts social worker had claimed that Brandon hung out with other kids who were involved in some recent neighborhood robberies.

But the robbery allegations were just rumors; Brandon hadnt been charged with that. As for the gun, well, Brandon lived in a terribly dangerous neighborhood, one where kids sometimes carried guns for self-defense. Most important, I had told Judge Walker, this was Brandons first arrest, and he had great potential. His football coach and two of his teachers had written letters about his promise, his family was supportive, and he had recently enrolled in a tutoring program for at-risk students. And Brandon had pleaded guilty, accepted responsibility for his actions, and been remorseful. Juvenile court was supposed to offer second chances, and Brandon was a perfect candidate.

The prosecutor argued that Brandon should go to Oak Hill, D.C.s juvenile detention facility. I had countered by pointing out what everybody knew: Oak Hill was a dungeon, with no functioning school, frequent incidents of violence, no counseling or mental health services worth the name, and no transition services for young offenders once they were released. Brandon would miss months of actual school while serving his sentence, and it was possible that the principal wouldnt take him back once he returned to his neighborhood. If this happened, there was no good alternative school he could turn to.

Brandon fidgeted as we waited for Judge Walker to speak, and I tried to calm him by placing my hand gently on the back of his shoulders. I glanced behind me and offered what I hoped was a comforting smile to Brandons mother and grandmother sitting in the first row. They had never missed a court hearing, had always voiced their support for Brandon. Now all they could do was wait.

Judge Walker finally gathered the papers up into one stack and placed them back in the case file. When he spoke, the verdict was quick and painful. Brandon, he said, I believe you have potential, and I see you have supportive teachers and family. But none of that was enough to stop you from picking up a gun. Even if I believe that you had it because you were scared, you could have hurt somebody. Son, actions have consequences. Your consequence is six months at Oak Hill. After which I hope you make good on the hopes that your mother and grandmother have for you.

That was it. The bailiff, who had been sitting behind us, stepped forward to take Brandon to a cell in the courthouse. Brandons mother gasped and started to cry. Judge Walker wouldnt like thatnone of the judges didbut what could he do now? The courtroom clerk would probably help her out into the hallway. Or so I hoped. I had to go see Brandon.

The cellblock was just a few feet behind the courtroom, but it was a world apart. No majesty here, no wood paneling, no carpeting or cushioned seats. Just metal and concrete, housing black boys like Brandon. And make no mistake about it: they were all black. That day, Brandons cell held three other black teens waiting for their cases to be called. The picture was the same in almost every D.C. courtroom, whether the accused were juveniles or adults. There were a few women and girls, but mostly men and boys. Nearly allaccording to official records, more than 95 percentwere African American.

This state of affairs was no secret. In 1995, the year Brandon came before Judge Walker, the Sentencing Project issued one of a series of increasingly alarming reports documenting blatant racial disparities in the criminal justice system. Nationally, one in three young black men was under criminal justice supervision. In Washington, D.C., the figure was one in two.

![Laura L. Finley - Crime and Punishment in America: An Encyclopedia of Trends and Controversies in the Justice System [2 Volumes]](/uploads/posts/book/305562/thumbs/laura-l-finley-crime-and-punishment-in-america.jpg)