NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS

New York

www.nyupress.org

2019 by New York University

All rights reserved

References to Internet websites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor New York University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

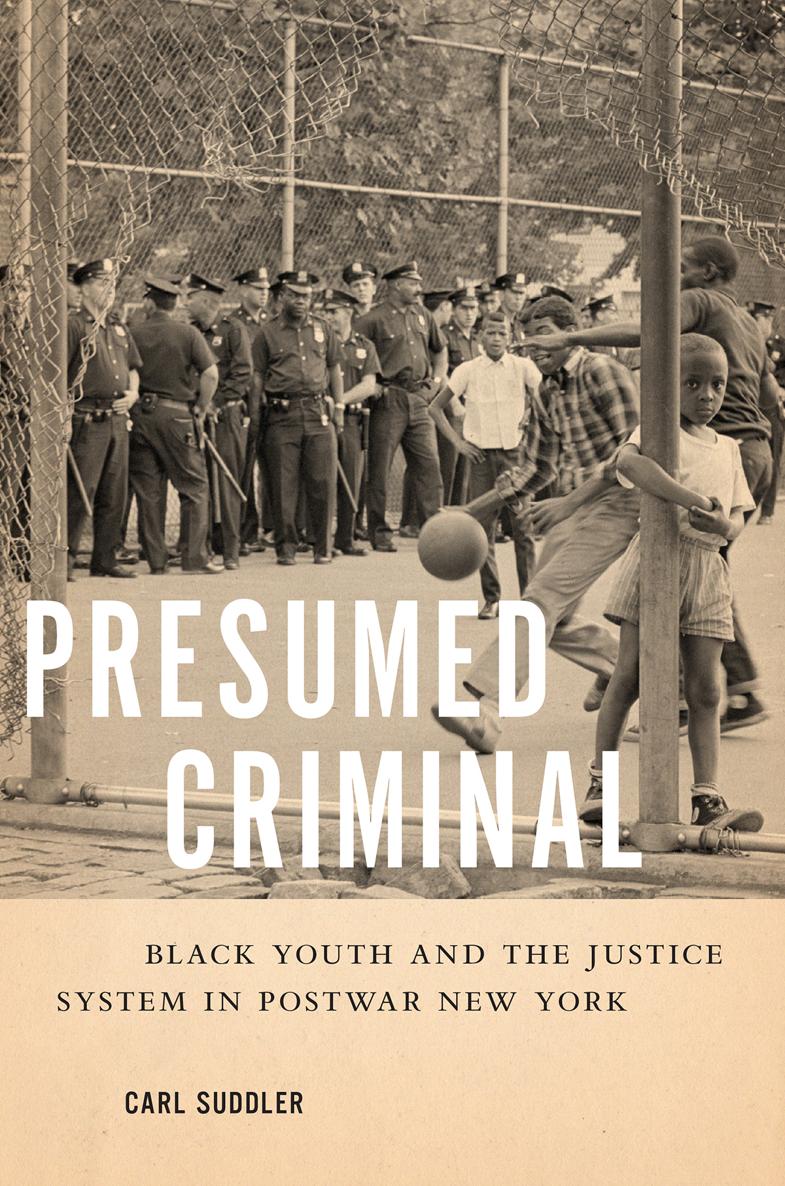

Names: Suddler, Carl, author.

Title: Presumed criminal : black youth and the justice system in postwar New York / Carl Suddler.

Description: New York : New York University Press, [2019] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018042634 | ISBN 9781479847624 (cl : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Juvenile delinquencyNew York (State)New YorkHistory20th century. | Youth and violenceNew York (State)New YorkHistory20th century. | African American youthNew York (State)New YorkSocial conditions20th century. | African AmericansNew York (State)New YorkSocial conditions20th century. | Discrimination in criminal justice administrationNew York (State)New YorkHistory20th century. | New York (N.Y.)Race relationsHistory20th century.

Classification: LCC HV 9106. N 6 S83 2019 | DDC 364.36089/9607307471dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018042634

New York University Press books are printed on acid-free paper, and their binding materials are chosen for strength and durability. We strive to use environmentally responsible suppliers and materials to the greatest extent possible in publishing our books.

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Also available as an ebook

Introduction

The Way I See It: Reframing Black Youth and Racial Injustice

A man never knows the real importance of fighting juvenile delinquency until he has to stare it in the face.

Roy Campanella, The Way I See It

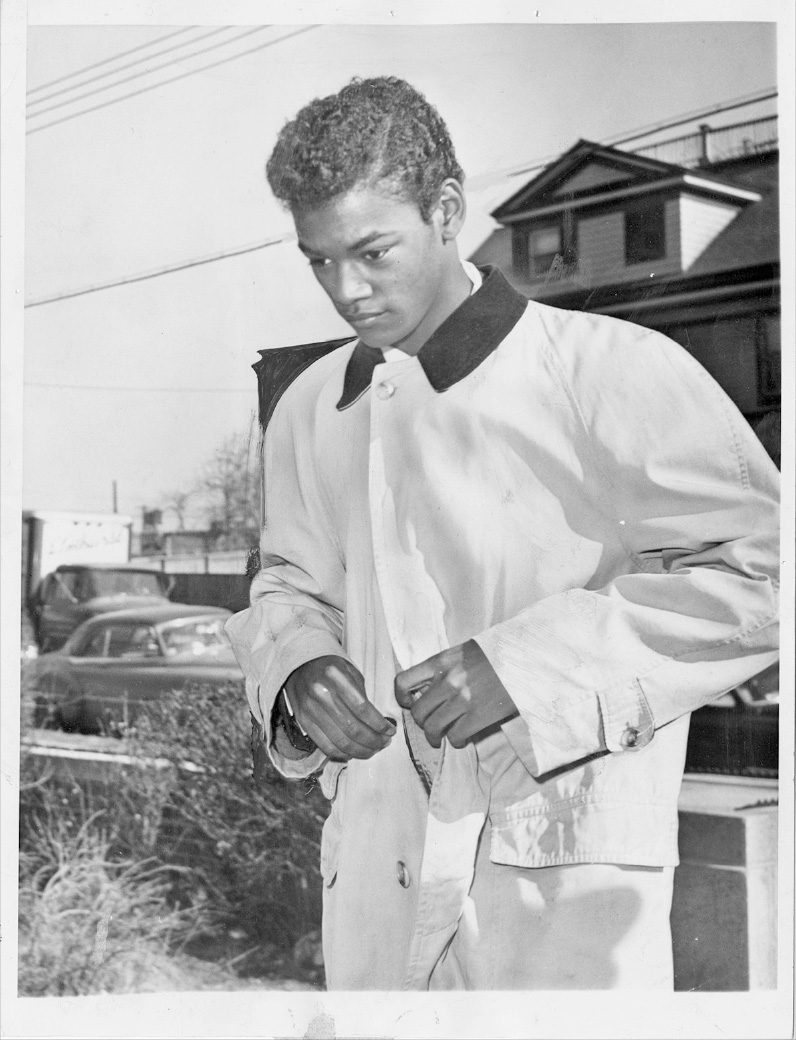

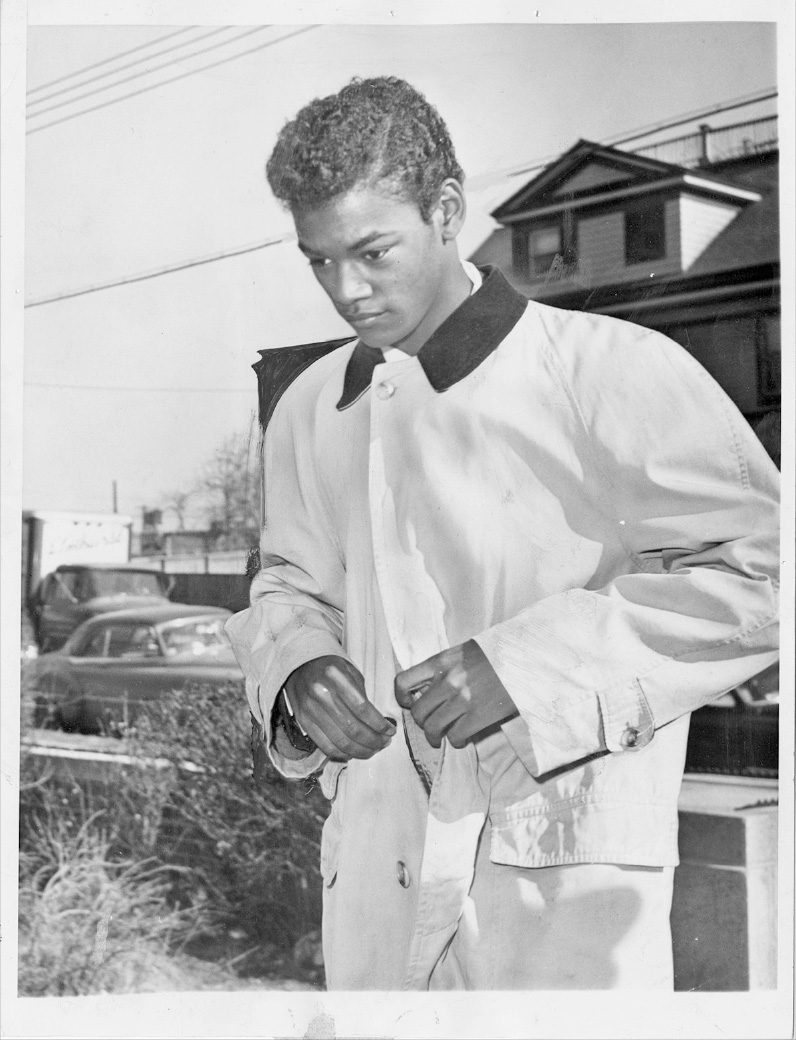

I just got mixed up with some jerky kids, David Campanella told the police when he was arrested for his role in a Queens brawl. According to police reports, the fifteen-year-old son of the former Brooklyn Dodger catcher Roy Campanella, was one of the six boys involved in a fistfight in the vacant parking lot of a bowling alley as roughly thirty boys from fourteen to twenty years old looked on. No weapons were involved, and no injuries were reported. Media coverage of the incident varied as the young Campanella was subjected to legal proceedings for the fracas. Still, even with his well-known surname, the black youth faced tremendous hardship in both the court of justice and the court of public opinion.

The first public accounts of the parking-lot scuffle were printed by New York newspapers, the New York Times and the New York Herald Tribune , with Campanellas photograph displayed and his name stamped in the headlines. There was not much discrepancy with regard to what happened on February 23, 1959; however, the New York dailies characterization of those who were involved differed. As reported by the Herald Tribune , David Campanella entered the Mapleways Bowling Alley and issued a challenge to a group of white boys to come out and fight. In accordance with the police report, Campanella was one of the leaders of the Chaplains, a Queens gang of Negro and Puerto Rican youths. The reason for the clash, according to the Herald Tribune story, was that the Chaplains had been piqued over their territorial rights in Flushing being taken over by the unidentified rival gang.

The unidentified rival gang was the Champions, a group of white youths who resided in the same neighborhood as the Chaplains. The New York Times coverage of the incident proclaimed that the Champions were said to have called the fight one week earlier to protest the presence of some of the Negro and Puerto Rican youngsters in a Flushing bowling alley. The Champions considered the bowling alley their territory and engaged Campanella and his guys when they entered Mapleways. One of the white boys who fought against the Chaplains, Mike ONeill, said, We were lounging around the bowling alley when Campanella and his two friends walked in. Campanella did all the talking. He said he wanted to build up a repyou know, a reputation in the neighborhoodand he wanted three of us to fight him and his guys. Three of us said we would and we did. Fourteen youths, between the ages of fifteen and twenty, were booked at the Flushing Precinct on charges of disorderly conduct, arraigned in Night Court before Magistrate Edward Chapman, and paroled to their parents custodyexcept Campanella.

The police escorted Campanella to the Bronx Youth House but did not release him to the custody of his mother, Ruthe, when she arrived to pick him up. Mrs. Campanella refused to talk to reporters, and the authorities at the Youth House did not immediately disclose why young Campanella was not discharged. Later it was learned that after David was detained for his role in the skirmish, he made damaging admissions concerning a burglary of a drugstore one week prior. Domestic Relations Judge Wilfred A. Waltemade explained to David, You must understand you have been found a juvenile delinquent and if you get in further trouble and are returned to childrens court, you have my word, boy, you will be dealt with very severely. Following a two-and-a-half-hour hearing, David was let go with a warning. His mother told reporters, This is going to break his fathers heart.

Roy Campanella, one of the first black, modern-era major-league baseball players, worked for many years with youngsters, mostly in New York City, to curb juvenile delinquency. In an article published by Jet magazine, an African American weekly founded in 1951, Roy Campanella revealed why it was important for him to work with kids around the country when he traveled with the Dodgers. For years Ive been lecturing in YMCAs, boys clubs and to kid groups about walking the straight and narrow, Campanella explained. Too, I felt I was making a contribution towards solving a really serious problem in American life. But like any father, Roy was forced to reexamine the whole picture of juvenile delinquency when he faced the problem firsthand. After his son, David, was released, Roy told New York Times reporters dejectedly, Everything else compared to this is nothing.

David Campanella, son of the Brooklyn Dodgers Roy, 1959. (Courtesy of Queens Borough Public Library, Archives, New York Herald-Tribune Photograph Morgue Collection)

The Campanellas scolded their son for his misbehaviors but at the same time understood the role that his reputable status played in the situation. As Mrs. Campanella defended her son in court, she affirmed that the charges were blown up all out of proportion because of his name. The familys attorney, William OHara, agreed. Objecting to the high bail the Campanellas were forced to pay, the lawyer told reporters that he wondered what would have happened to this boy if his name were Johnny Jones. Though it is difficult to know for certain to what extant Davids family name affected the courts response to his wrongdoings, the press openly admitted that its coverage of the Campanella case was indeed influenced by his last name. Objecting to the tacit rule not to publish the names of juvenile offenders, the managing editor of the New York Times , Turner Catledge, disclosed, It is not the purpose of newspapers to prevent crime or to sell any philosophy to the public. Unrelenting in his sentiment that the press was obligated to give the public facts, in reference to the Campanella case, Catledge stated, We in New York have much less to apologize for than if we had not printed the name. Names do make news.