The views and opinions expressed in this book are solely those of the author and do not reflect the views or opinions of Gatekeeper Press. Gatekeeper Press is not to be held responsible for and expressly disclaims responsibility of the content herein.

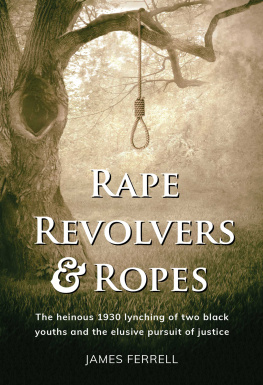

Rape Revolvers & Ropes: The heinous 1930 lynching of two black youths and the elusive pursuit of justice

Published by Gatekeeper Press

2167 Stringtown Rd, Suite 109

Columbus, OH 43123-2989

www.GatekeeperPress.com

Copyright 2020 by James Ferrell

All rights reserved. Neither this book, nor any parts within it may be sold or reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems without permission in writing from the author. The only exception is by a reviewer, who may quote short excerpts in a review.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2020939460

ISBN (paperback): 9781662901539

eISBN: 9781662901522

T ABLE OF C ONTENTS

T HIS BOOK IS a historical account of an incredibly dark era in America. It provides gruesome details about the lynchings of two African-American teenagers in 1930. This book also chronicles the blatant racism that was a part of everyday life in this small midwestern town. Symbols of racism jump out at you throughout this document.

The language will elicit a visceral reaction in most. In 1930, many whites used the most derogatory term available to name blacks. No one in their right mind would use that word today. Yet, this text does. Direct quotes from this era give you, the reader, insight into white attitudes about and treatment of minorities. Some of the opinions expressed by police, reporters, and newspaper editors may shock you.

Others may experience emotional responses when reading newspaper ads that use black-face characters or caricatures of African Americans. The examples in this book are typical of that time in history. Also, there is one photograph of the two youths hanging from a tree that may particularly outrage you. The atrocity captured by this photo is gut-wrenching, yet, it too is part of our past.

The author has chosen not to sanitize the language, images, and photographs of 1930. He believes that it is important for the past to be seen as it was. Any effort to rewrite the human experience is a disservice to society. We will never know where we are going unless we accept accurate historical accounts of where we have been.

(The Latin term [sic] (thus was it written) notes that any potentially offensive language in this text is a direct quotation, all of which are properly referenced.)

W HEN I WAS around fourteen, my grandfather told me about his life as a young man in Marion, Indiana when he added, They hung two niggers (sic) down on the courthouse square. He explained that two young Negros killed a white boy and raped his girlfriend. My grandmother, who stood no more than four foot seven, gave him the sternest look that I had ever seen. She raised her voice and said, RUSSELL! After her outburst, I could never get him to talk about the lynchings again. Neither of my parents grew up in Marion, so when I asked them, they both said that they did not know anything about it. You will find that not knowing anything is a thread that runs throughout this historical account.

Many years later, curiosity got the best of me and I began investigating what really happened. Since I didnt know anything about conducting historical research or writing historical details, I enrolled at California State University in Fullerton, California to pursue a Masters of Arts Degree in History. What I learned in that program gave me the information and confidence I needed to begin researching these events. Unfortunately, at that time I was living in Southern California and Marion, Indiana was about 2,000 miles away. As a result, I made annual trips back to Marion to hunt for the truth.

As I began my search, I found that the Marion Public Library contained a treasure trove of information. In 1930, when the lynchings occurred, Marion had two daily newspapers: The Marion Leader-Tribune and The Marion Chronicle . The Library has retained microfilm copies of every issue of both papers from the mid-1800s to the present. The microfilm spools and readers provided me the details of these events. The Librarys archives also contained copies of other newspaper articles about the lynchings; most of the daily newspapers in towns close to Marion reported on these events as well. This history references all of these papers in the ensuing story. In addition, papers as far away as Chicago and New York also published articles about these incidents.

Since murders lead to indictments and indictments initiate trials, it only seemed logical that the Grant County Court House, located in the center of Marion, contained an extensive array of information related to these legal events. On my first visit to the County Records Office in the Court House, I made the mistake of asking for any records they had that related to the 1930s lynchings. As soon as the word lynchings left my mouth, the clerk and her assistants looked at me as if I had just blasphemed. They curtly explained that they did not know anything about any records concerning lynchings. They promptly dismissed me from their office.

The next time I visited Marion, my high school and college friend Randy Johnson, a Grant County judge, intervened on my behalf. He called the County Clerk and told her that I needed access to the 1930s records. The Clerk grudgingly led me up a set of rickety stairs to the attic of the Court House. What I found could have been a scene from a horror movie. Cobwebs, bird droppings, and a thick layer of dust covered hundreds of aging and hand-written books of court records that were strewn all over the floor and bookshelves. If I had had weeks rather than hours to scour this room, I might have found what I was looking for. Unfortunately, after searching briefly, I gave up and moved on to my next potential source of information.

My investigation revealed that the court system had moved Camerons trial from Grant County to Hamilton County. Hamiltons courthouse is in Anderson, Indiana. On another trip to Marion, I made the thirty-mile drive to Anderson and entered the County Records Office. Learning my lesson from Marion, I asked if they had any trial records and/or trial transcripts from 1931. Initially, I did not say the word lynching. In our discussion, I finally disclosed that I was searching for information about the hangings. Although extremely friendly, their Records Office had no information for me. The clerks and supervisor offered that they did not know anything about a trial related to a lynching. I knew that I needed to look elsewhere on my next visit to Indiana.

Back home in California, I reviewed all of the information I had collected and discovered that there was an Indiana Historical Archive located in Indianapolis. A year later, on my next trip to Indiana, I visited the Archive. Although this facility did not house any relevant court transcripts, it did have over three hundred pages of depositions that were collected and transcribed shortly after the Marion lynchings occurred. Because these historical records are too long to use verbatim in this book, I quote from some of them to clarify the reports in the newspaper articles. They also provided a look behind the headlines as these individuals gave their affidavits in secret. The authorities did not release these statements to the public until many years after the courts conducted the trials.