Contents

Guide

Pages

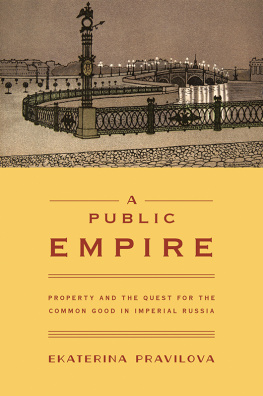

New Russian Thought

The publication of this series was made possible with the support of the Zimin Foundation.

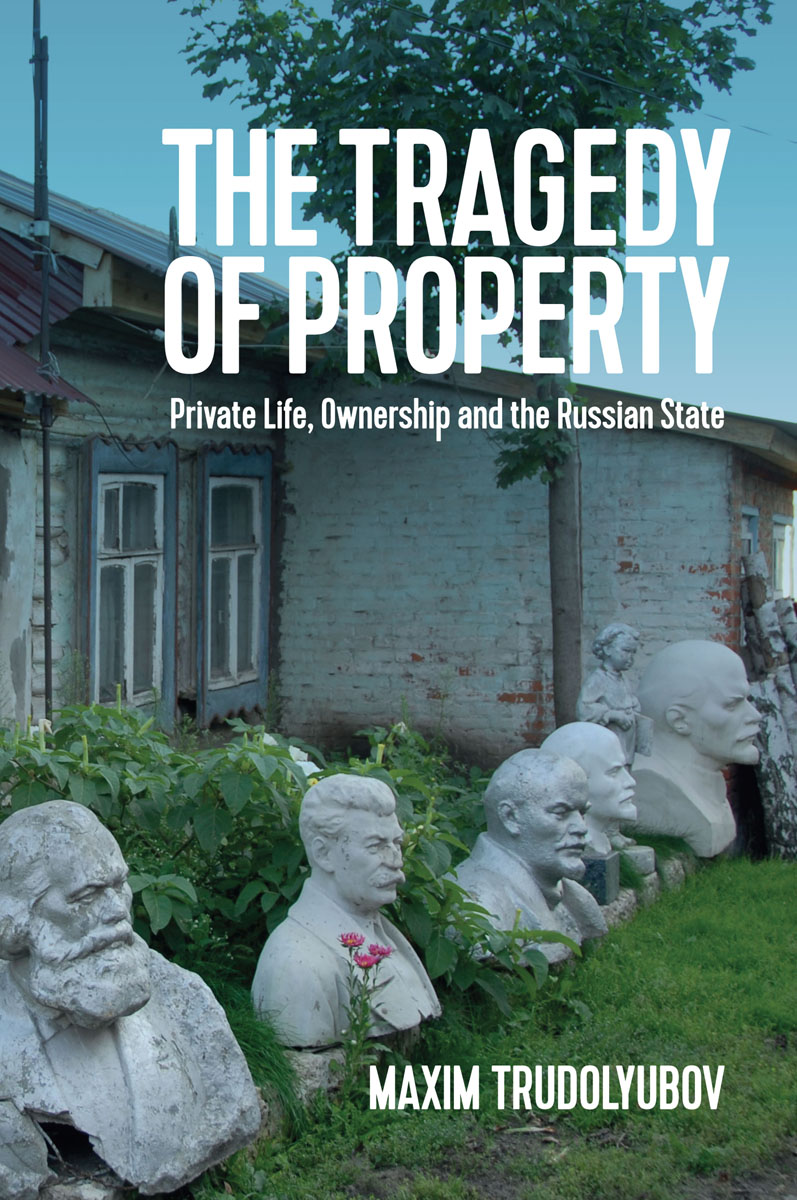

Maxim Trudolyubov, The Tragedy of Property

The Tragedy of Property

Private Life, Ownership and the Russian State

Maxim Trudolyubov

Translated by Arch Tait

polity

First published in Russian as : , [People Behind the Fence: Private Space, Power and Property in Russia]. Copyright 2015 by Novoye Izdatelstvo. This edition is a translation authorized by the original publisher.

This English edition Polity Press, 2018

This book was published with the support of the Zimin Foundation.

Polity Press

65 Bridge Street

Cambridge CB2 1UR, UK

Polity Press

101 Station Landing

Suite 300

Medford, MA 02155, USA

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN-13: 978-1-5095-2704-5

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Trudolyubov, Maxim, author.

Title: The tragedy of property : private life, ownership and the Russian state / Maxim Trudolyubov.

Description: Cambridge, UK ; Medford, MA : Polity Press, [2018] | Series: New Russian thought | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017059735 (print) | LCCN 2018006032 (ebook) | ISBN 9781509527045 (Epub) | ISBN 9781509527007 (hardback) | ISBN 9781509527014 (pbk.)

Subjects: LCSH: Property and socialism--History. | Property--Russia (Federation)--History. | Property--Soviet Union--History. | Russia (Federation)--Politics and government. | Soviet Union--Politics and government.

Classification: LCC HX550.P7 (ebook) | LCC HX550.P7 .T78 2018 (print) | DDC 306.3/20947--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017059735

The publisher has used its best endeavours to ensure that the URLs for external websites referred to in this book are correct and active at the time of going to press. However, the publisher has no responsibility for the websites and can make no guarantee that a site will remain live or that the content is or will remain appropriate.

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition.

For further information on Polity, visit our website: politybooks.com

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

My wife, Inna Beryozkina, has provided invaluable assistance during the writing of this book, as have Matvey Trudolyubov, who grew up along with it, and Maria and Pyotr Trudolyubov.

The book, and not only the book, has benefited immensely from my good fortune in knowing and conversing with: the philosophers and founders of the Moscow School of Civic Education, Yelena Nemirovskaya and Yury Senokosov; historian Vasiliy Rudich; economists Sergey Guriev, James Robinson, Konstantin Sonin, Oleg Tsyvinsky, Kirill Yankov and Vladimir Yuzhako; political scientist Ivan Krastev; political analyst Ellen Mickiewicz; Russian language and literature specialist Mikhail Gronas; architect Nikita Tokarev; businessmen Alexey Klimashin, Sergey Petrov and Bulat Stolyarov; Matthew Rojansky, director, and William E. Pomeranz, deputy director, of the Kennan Institute at the Woodrow Wilson Center, Washington, DC; and my colleagues at Vedomosti Pavel Aptekar, Boris Grozovsky, Andrey Sinitsyn, Nikolai Epple and Nikolai Kononov. The book would never have seen the light of day without the active participation of editor Andrey Kurilkin, who agreed to read the manuscript in the first place, accepted it and helped to improve it.

The high professionalism and intellectual distinction of my associates cannot guarantee a finished product of equally high quality, and culpability for shortcomings and errors lies squarely with me.

FOREWORD

In 2014, the revolution in Ukraine forced President Viktor Yanukovych to flee to Russia. The rebels entered his private, well-fenced residence near Kiev, which previously had been secured by dozens of heavily armed guards. In post-Soviet history, it was probably the first but surely not the last break-through into the intimate life of power. What the public mostly students and impoverished intellectuals saw in the residence was ridiculous rather than sublime. Palladian columns, gilded walls and pseudo-rococo furniture produced a strange feeling of bad taste with historical resonances: here the reminiscences of Austro-Hungarian glory, there the replicas of socialist realism, plus some imitations of the slave-holding American South to boot. Well connected and even better protected, Mr Yanukovych now lives in a smaller mansion near Moscow, where his neighbours cannot help but think about his fate.

In this book, Maxim Trudolyubov depicts contemporary Russia from an unusual but uniquely relevant perspective the history of space. This perspective is relevant because in many ways Russia is equal to its space, and contemporary Russia particularly so. It is the integrity of space that has been the highest political value for Russian rulers, and the disintegration of the Soviet Union added fresh and traumatic undertones to this age-old sentiment. Even the ruling party calls itself United Russia rather than, say, Happy Russia. The largest country in the world by landmass, Russia has developed its historical particularities in the millennial effort to capture, protect and cultivate the enormous territory of northern Eurasia. Sustaining life in this space has, historically, not been a trivial issue, and unusual instruments of indirect, communal organization were developed for the purpose. In the massive literature on Russian history, Trudolyubovs book is unique in presenting the long and tortured story of Russian property arrangements in one coherent narrative. From land communes to communal apartments to late Soviet condominiums to the exorbitant inequality that is characteristic of contemporary Russia, we feel a bizarre, contingent logic to these twisted and often inverse developments. Introduced by the state, property regulations partially resolved and partially exacerbated the enormous difficulties and complexities of space and property in Russia.

Our neoliberal age has translated the problems of Russian space into legal regulations of private property on land, housing, apartments and, inevitably, fences. Trudolyubov demonstrates the ambivalent and tortured, even tragic, nature of the process. Russian history is a history of self-colonization, and Trudolyubov elaborates on this dictum. From the patriarch of Russian historiography, Vasiliy Kliuchevsky, to my recent Internal Colonization (2011), this story of Russias external and internal colonization has been told mostly from the perspectives of political, cultural and economic history. Independently of its declared purposes, colonization leads to tragic results. This book demonstrates that there is no better perspective on the unique character of Russian history than its space management, property regulations, privatization campaigns, enclosures and fences. This book is also about the tragedy of post-socialist capitalism, a massive but peculiar version of political and cultural economy that is still waiting for its Adam Smith.