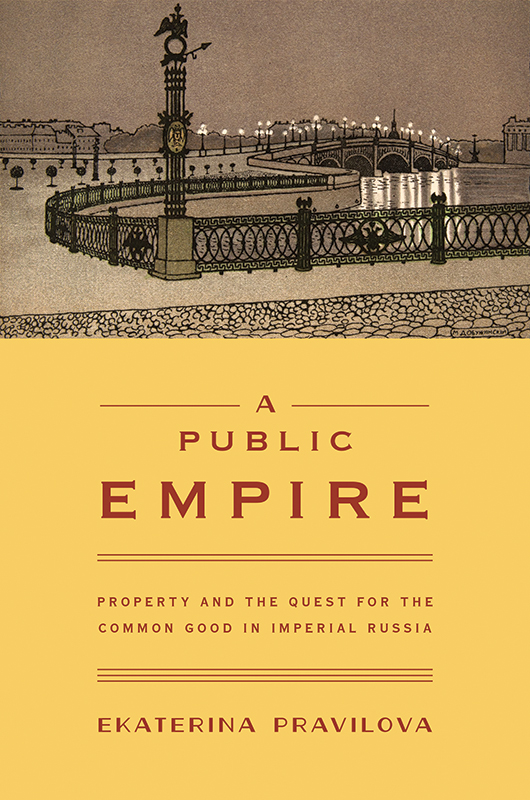

A Public Empire

A Public Empire

PROPERTY AND THE QUEST FOR THE COMMON

GOOD IN IMPERIAL RUSSIA

Ekaterina Pravilova

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS R PRINCETON AND OXFORD

Copyright 2014 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

press.princeton.edu

Jacket illustration: Mstislav Dobuzhinskii, Troitskii most, 1903, postcard. 2014 The State Russian Museum.

All Rights Reserved

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Pravilova, E. A. (Ekaterina Anatolevna), author.

A public empire : property and the quest for the common good in imperial Russia / Ekaterina Pravilova.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-691-15905-8 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Public domainRussiaHistory. 2. Right of propertyRussiaHistory. 3. Government ownershipRussiaHistory. 4. RussiaHistory16131917. I. Title.

KLA3040.P73 2014

333.1094709034dc23 2013028580

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Minion Pro

Printed on acid-free paper

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

CONTENTS

PART I

Whose Nature? Environmentalism, Industrialization, and the Politics of Property |

PART II

The Treasures of the Fatherland |

PART III

Estates on Parnassus: Literary Property and Cultural Reform |

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

One cant undo a knot with one hand, says an old Russian proverb attesting to the vanity of solitary work, and this is certainly true about my work on this book. Many hands (and minds) have joined together to help me untangle the knot and sort out the complexities of Russian thinking about property, and I am deeply indebted to everyone who has assisted me with their encouragement, assistance, and friendly critique.

The idea for this book originated with a paper that I delivered at a workshop on the Materiality of Res Publica hosted by the European University in St. Petersburg in 2007. I am grateful to all the workshop participants and especially to Professors Oleg Kharkhordin and Quentin Skinner for the initial inspiration to explore the world of public things in the Russian context. In addition to this, I presented earlier versions of what have now become a number of the books chapters at a variety of academic venues and in each case greatly benefited from the advice of numerous colleaguesin particular, the organizers of and participants in the Russian kruzhok at Princeton University; the Russian history workshop at Columbia University; the workshops on Russian and Soviet History and Culture and Economic History at the University of Pennsylvania; the Russian History Workshop at the Center of Russian, East European, and Eurasian Studies at the University of Michigan; and the Russian workshop at Georgetown University. Numerous friends and colleagues then helped me once I began work on the manuscript: Zhanna Kormina helped me untangle the particulars of Orthodox ritual; Edyta Bojanowska, Caryl Emerson, Serguei Oushakine, William Mills Todd III, and Michael Wachtel opened my eyes to the politics of literary property in the imperial era; and Tatiana Borisova, Yanni Kotsonis, Alberto Masoero, and Paul Werth each read individual chapters in a number of different incarnations, offering me suggestions that helped me to greatly improve my argument. I also shamelessly abused the generosity of Peter Holquist, who introduced me to numerous references and research materials, commented on multiple papers and articles, and kindly read the manuscript both as a whole as well as piece by piece. Last, I am endlessly grateful to Jane Burbank, Michael Gordin, Stephen Kotkin, Philip Nord, and Willard Sunderland, who generously took on reading the entire manuscript and shared comments and criticisms that always pushed me to write the best book I could. Any of the shortcomings that remain are all my own.

The Department of History at Princeton has been my intellectual home since I began work on this project. Conversations over the years with Jeremy Adelman, Molly Greene, Hendrik Hartog, Yair Mintzker, Rebecca Rix, and Martha Sandweiss have helped me to look at the issues of property in a broader context. I am also deeply indebted to my teacher and academic advisor Boris Vasilievich Ananich for everything to date that I have been able to produce as a historian. Boris Vasilievich has taught me the subtleties of the historians craft and has constantly supported me in all my academic endeavors.

A number of institutions provided the critical financial and logistical support that I needed to complete my project. A Charles A. Ryskamp Research Fellowship from the American Council of Learned Societies gave me much needed support for research and writing, while Princeton Universitys Committee on Research in the Humanities and Social Sciences generously sponsored several years of research trips to Russia, Georgia, and Ukraine. In 20102011, I had the good fortune to spend a year working on my manuscript at the New Economic School (NES) in Moscow. One cannot imagine a better place than the NES to write a book, and I am endlessly grateful to Sergei Guriev, Igor Fedyukin, and Konstantin Sonin for inviting me to the school and to all my colleagues there for their enduring friendship and support.

Anne ODonnell has edited numerous versions of this text: I am deeply grateful to her for her efforts to add smoothness and elegance to my nonnative English. Margarita Emelina and Tatiana Voronina have been wonderful research assistants: their work made a huge difference for my work in Russian libraries and archives. I have also benefited from the kind assistance of numerous Russian academic institutions and repositories, though I owe special thanks to Irina Zolotinkina and Vera Kessenich of the Russian Museum, Natalya Andreevna Belova of the Institute of the History of Material Culture, and Anna Gorskaia of the Museum of Art and History in Murom.

I am grateful to the editors of Kritika: Exploration in Russian and Eurasian History and Annales. Histoire, Sciences Sociales for allowing me to use the portions of articles that have appeared in these editions as The Property of Empire: Islamic Law and Russian Agrarian Policy in Transcaucasia and Turkestan, Kritika: Explorations in Russian and Eurasian History, vol. 12, no. 2 (Spring 2011), pp. 353386, and Les res publicae russes: Discours sur la proprit publique la fin de lEmpire, Annales HSS, vol. 64, no. 3 (2009), pp. 579609, Ehess, Paris. Chapters incorporate these materials in revised form.

By now, my husband, Igor, knows by heart all my stories about forests and icons; over the years, he has been both my most engaged critic and my foremost fan. I am deeply grateful for all he has done to help me. My father, Anatolii Mikhailovich, a scientist and himself an author, knows all too well the joys and hardships of academic writing; his relentless nagging to make sure I met my deadlines gave me the motivation to keep moving forward. My mother, Natalya Vasilievna, took care of my children during several archival trips and traveled across the Atlantic to babysit while I was struggling to finish the last chapters. Zhenia and Liza do not know much yet about the intricacies of propertyexcept perhaps for their claims to toys and computer games. However, they will be glad to know that this particular property book is over.

Next page