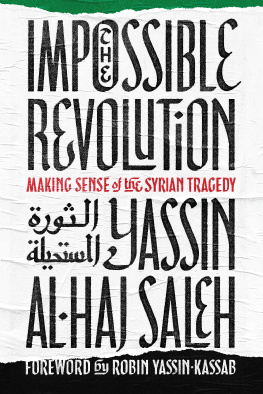

THE

IMPOSSIBLE REVOLUTION

Making Sense of the Syrian Tragedy

Yassin al-Haj Saleh

Foreword by Robin Yassin-Kassab

Haymarket Books

Chicago, Illinois

First published in the United Kingdom in 2017 by

C. Hurst & Co. (Publishers) Ltd., London

Yassin al-Haj Saleh, 2017

Translation Ibtihal Mahmood

All rights reserved.

This edition published in 2017 by

Haymarket Books

P.O. Box 180165

Chicago, IL 60618

773-583-7884

www.haymarketbooks.org

ISBN: 978-1-60846-875-1

Trade distribution:

In the US, Consortium Book Sales and Distribution, www.cbsd.com

In Canada, Publishers Group Canada, www.pgcbooks.ca

In the UK, Turnaround Publisher Services, www.turnaround-uk.com

All other countries, Ingram Publisher Services International,

IPS_Intlsales@ingramcontent.com

This book was published with the generous support of Lannan Foundation and Wallace Action Fund.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data is available.

To Samira, the auspicious symbol of Syria,

And to Syria, the symbol of a progressively Syrianized world.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

For a long time, I resisted the temptation of publishing a book about the Syrian revolution. Writing from within a great upheaval, I was worried about my own naivety. It is possible that I carried the seeds of this apprehension from Hegel, some of whose work I had read during my years in prison. This German philosopher said that we live the present with a naive consciousness. This naivety stands in opposition to absolute knowledge, a Hegelian concept that entered Marxist thought under the rubric of science and scientific socialism. The Syrian revolution released me from such Hegelianisms. For me, naivety has come to mean the shahada (testimony) of a witness, my own shahada about what I was part of, and my sense of things when the seemingly impossible erupted into vivid existence in my country. The impossible was a revolution.

And in the course of six years, that impossible was crushed out of existence. So maybe it is time in this seventh year to tell the story, or to retell it, to try to represent our struggle.

This shahada would have been impossible to put together as a book if it were not for the initiative and the valuable help of Danny Postel and Nader Hashemi from the Center for Middle East Studies at the University of Denver in the US. Without previous personal acquaintance, Danny and Nader introduced me and my work to wider circles of readers when I was still walking my first steps outside Syria in early 2014.

I cannot thank Kelly Grotke and Stephen Hastings King enough. Along with Nader and Danny, they are the embodiment of solidarity and partnership. Even more, humanity. Steve and Kelly helped diligently with this book, as if it were their own. It is.

Everything would have been far more difficult in Turkey if it were not for Senay Ozdens invaluable help in so many ways. Her comments on many points made in this book were always insightful and illuminating.

And of course I bear responsibility for any mistakes in information or analysis. The shahid (the one who gives a shahada ) does not expect any tolerance about this.

Istanbul, February 2017

FOREWORD

Robin Yassin-Kassab

The world is sick and its sickness is aggravating our sicknesses,

both inherited and acquired .

Yassin al-Haj Saleh is a burningly relevant political thinker. Unlike most of his counterparts, he speaks not only from theory but from a lived experience of repression, revolution, counterrevolution, and war. Objective but never neutral, he is engaged and in tune with the rapid shifts and turns of his tormented society, urgently seeking answers to the most wide-ranging and inclusive of questions, and unearthing more, previously un-thought of, questions as he goes.

His context is Syria, where 12 million are homeless, and perhaps half a million dead. Syria which, in the seventh year of the upheaval, has become a truly global issue. The war Assad unleashed to marginalise and destroy a democratic opposition has given rise to a series of increasingly complicated conflicts, often bearing ethnic or sectarian tones. Fanned by overlapping, sometimes competing foreign interventions, these conflicts have infected the region and the world in turn. Regional and international imperialisms are feasting on Syria. Battle lines and forced demographic changes are fueling a hunger to redraw the maps. The spectre of Syrian refugees and/or terrorists, meanwhile, is shaping Americas domestic politics and helping undo the European Union. As hopes for freedom and prosperity are crushed, new strains are injected into old authoritarianisms, and twenty-first century forms of nativism are taking root, west and east.

Yassin speaks from the heart of this turmoil. Yet, you hold in your hand the first book-length English translation of his work.

Its been a long time coming.

They simply do not see us, he laments. If we dont see Syrian revolutionaries, if we dont hear their voices when they talk of their experience, their motivations and hopes, then all we are left with are (inevitably orientalist) assumptions, constraining ideologies, and pre-existent grand narratives. These big stories, or totalising explanations, include a supposedly inevitable and ancient sectarian conflict underpinning events, and a jihadist-secularist binary, as well as the idea, running counter to all evidence, that Syria is a re-run of Iraq, a Western-led regime-change plot. No need to attend to detail, runs the implication, nor to Syrian oppositional voices, for we already know what needs to be known.

Purveyors of such mythsideologues and regime-embedded journalists, experts who dont speak more than a few words of Arabicoften seem to rely on each other to confirm and develop their theories. They brief politicians, they dominate opinion pages, learned journals and TV panels. And, to a large extent, we the public rely on them too. We see through their skewed lens, through a certain mythic framework which covers the Syrian revolution only in the sense of hiding it from view. As a result we are unable either to offer solidarity to this most profound and thoroughgoing of contemporary social upheavals, or to learn any lessons from it.

Yassin al-Haj Saleh was born in 1961 in a village near Raqqa. His concern for social justice arose from his immediate environs: the poor rural hinterland of a troubled post-colonial state.

Karam Nachar, an academic and sometime collaborator of Yassins, illustrates Syrias urban/rural and class divides by comparing the situation of his relatives in bourgeois Aleppo, who attended cinemas back in the 1920s, witha mere 200 kilometres awaythe Raqqa that Yassin grew up in forty years later, where there were still no cinemas, nor even paved roads.

While studying medicine in Aleppo, Yassin joined the Syrian Communist Party (Political Bureau), a group formed in 1972 after the mainstream Communist Party had been co-opted by the Assad regime. The Political Bureau advocated democracy as well as social justice, and agitated against the regimes 1976 intervention in Lebanon on the side of right-wing Falangists.

Yassin was arrested in 1980, and languished as a political prisoner for the next sixteen years. He spent the last year in Tadmor prison, near the ruins of Palmyra. Tadmor is a name, or a crime scene, which resonates terribly in the Syrian imagination. Poet Faraj Bayraqdar, a fellow prisoner, called Tadmor the kingdom of death and madness.

But languish is not quite the word. Despite the torture and unliveable conditions, Yassin read and thought as much as he could, liberating himself from the internal prisons of political and ideological regimentation. With Salvation, Oh Youth: Sixteen Years in Syrian Prisons is his memoir of the period, an addition to Syrias rich prison literature genre (though Yassin, considering all of Assads Syria a prison, preferred to slip the label and categorise the text more generally as a matter of concern).

Next page