SEAPOWER STATES

Copyright 2018 Andrew Lambert

All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press) without written permission from the publishers.

For information about this and other Yale University Press publications, please contact:

U.S. Office:

Europe Office:

Set in Minion Pro by IDSUK (DataConnection) Ltd

Printed in Great Britain by Gomer Press Ltd, Llandysul, Ceredigion, Wales

Library of Congress Control Number: 2018953243

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The State is a work of Art.

Jakob Burckhardt

For my Mother

CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS AND MAPS

Plates

Pictures in the text

Maps

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

As any manuscript heads for publication authors return to the beginning, to reflect on the debt they owe to others, fellow scholars, students, family and friends, delightfully loose categories reflecting the reality that the first and last are often one and the same. Furthermore, as a historian I am acutely conscious of my debt to those who have gone before, a debt we honour by reflecting on works written long go, for very different audiences. The ideas and arguments of these authors run through this book, they are the building blocks for what follows. I cannot thank them in person, and only hope they would not be too offended by what I have made of their work.

Many friends and colleagues in the academic world have shared in the debate, offered fresh material and sage advice. I cannot thank them enough, and any attempt to be comprehensive would be foolhardy. First on the list is my old friend John Ferris, who has entertained more iterations of this thesis than anyone else. He provided sound advice, clear judgement and honest criticism, as did Beatrice Heuser, another friend of many years, and Richard Harding; all three have shared their expertise in fields that range far wider than the historical, and recognised the rhyme in the text. My colleague Alan James, with whom it has been a pleasure to share the naval history curriculum at Kings College London, read the manuscript and discussed the many things that separate France and England with his delightfully wry detachment. His support, and that of the War Studies Department, is greatly appreciated. Maria Fusaro, Larrie Ferreiro and Gijs Rommelse read draft chapters that crashed into their fields of expertise, corrected my errors and provided excellent advice. Michael Tapper and Catherine Scheybeler read the whole thing, and despite instructions to the contrary Catherine proofread the penultimate draft, picking up more keying infelicities and errors than even the author had expected. Many more friends and colleagues have helped turn the initial premise into a coherent argument, directly or otherwise, and I can only hope they will not be too disappointed by the result.

Thanks are also due to Paul Kennedy, who encouraged me to pursue my interests forty years ago, the late Bryan Ranft, who taught me far more than I realised at the time, Sir Lawrence Freedman, for allowing me to work in the best department in which to write such a book, and his successors who have retained the unique multidisciplinary ethos. Many of my colleagues in War Studies have supported the project, with words, ideas, time and the unique camaraderie of the place, none more so than Alessio Patalano, a student of seapower identity in East Asia and elsewhere, and Marcus Faulkner and Carlos Alfaro Zaforteza, who spoke up for alternative continental models of naval power.

This book is built on the scholarship of others, books, articles and other outputs: the one quotation from an archival source was borrowed from another project, because it expressed the argument so perfectly. Today such research is greatly aided by access to online resources, books, journals and data that still seem magical to someone who began work in the era of the card index, pencil and typewriter. Modern scholarship has fewer barriers, but this cornucopia challenges us in different ways. Setting boundaries has become the big issue, and in a book that is intended to generate debate I chose brevity and concision. I am only too well aware of the obvious limitations imposed by that choice, but without it the project would have outlasted the author, the timelines of the REF (Research Excellence Framework, next due in 2021), and the patience of readers.

Once again Julian Loose has overseen the process of the book, from commissioning to completion, with the able assistance of the team at Yales London office, and Richard Mason, who has removed the inevitable authorial obscurities with great skill. Despite the best efforts of friends and colleagues imperfections will remain, and for those I alone am responsible.

My family has been with me throughout the project. Their support has been unwavering, and essential. Words cannot express how much that means, and why it mattered so much.

Andrew Lambert

Kew, 5 April 2018

PREFACE

HMS Hood, the 191941 iconic vessel of the last seapower

In 1851 an English intellectual grappled with the great question that has preoccupied mankind since the dawn of civilisation, the future of the political unit in which they live:

Since first the dominion of men was asserted over the ocean, three thrones, of mark beyond all others, have been set upon its sands: the thrones of Tyre, Venice, and England. Of the First of these great powers only the memory remains; of the Second the ruin; the Third which inherits their greatness, if it forget their example, may be led through prouder eminence to less pitied destruction.

John Ruskin understood that Britain was unusual, a great sea empire, not a continental power, and that it was also the only such state in the contemporary world. As the self-appointed champion of J. M. W. Turner, the artist who elevated the imagery of the sea from the prosaic to the sublime in his pursuit of a British seapower identity, Ruskin had followed his hero to Venice. There, beside the Grand Canal, he discovered the tools he needed to The tragic beauty of the image, the elegance of Ruskins phrasing and the deceptive simplicity of the message confronted a nation, glorying in the year of the Great Exhibition, with the reality of decline.

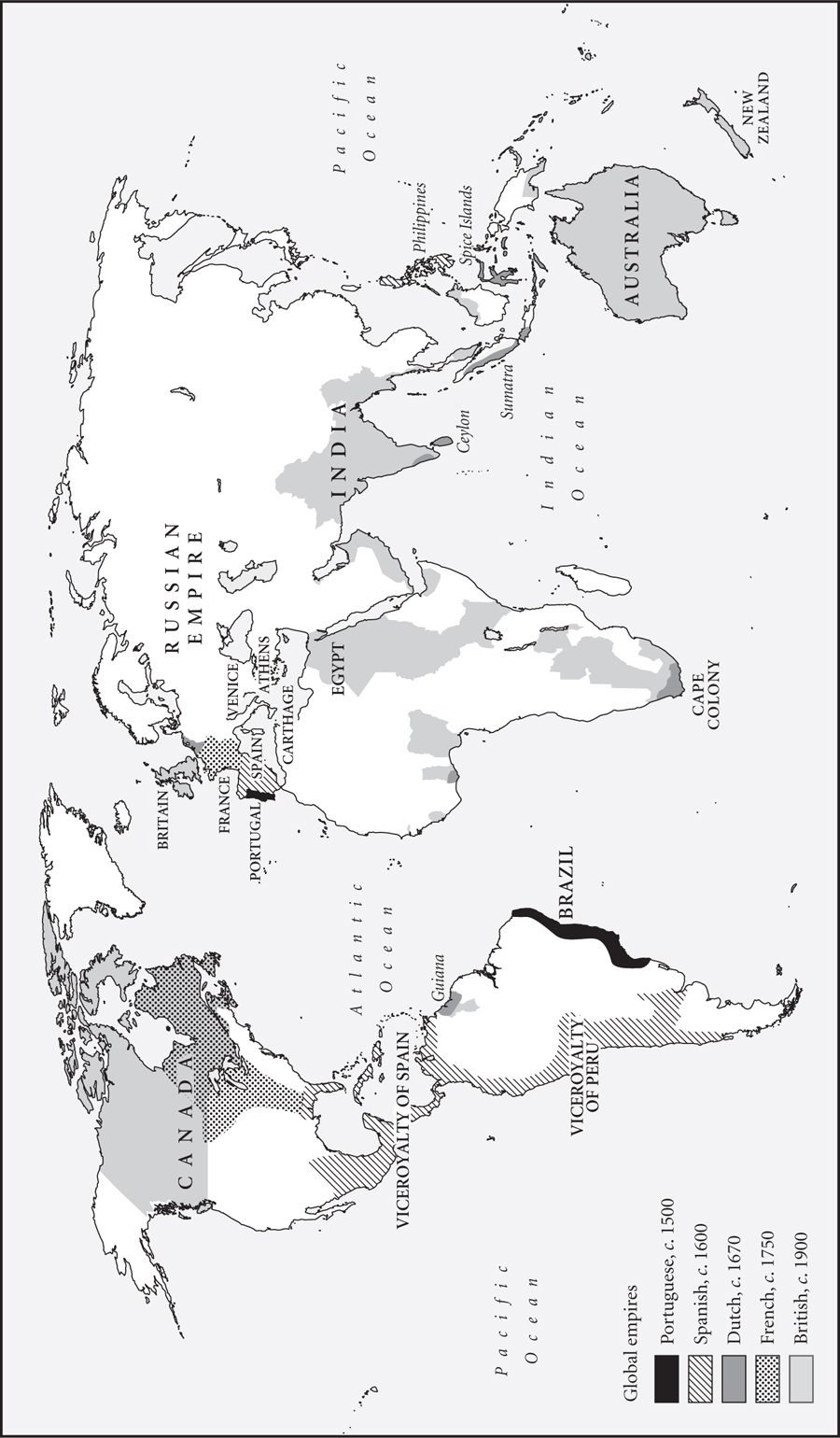

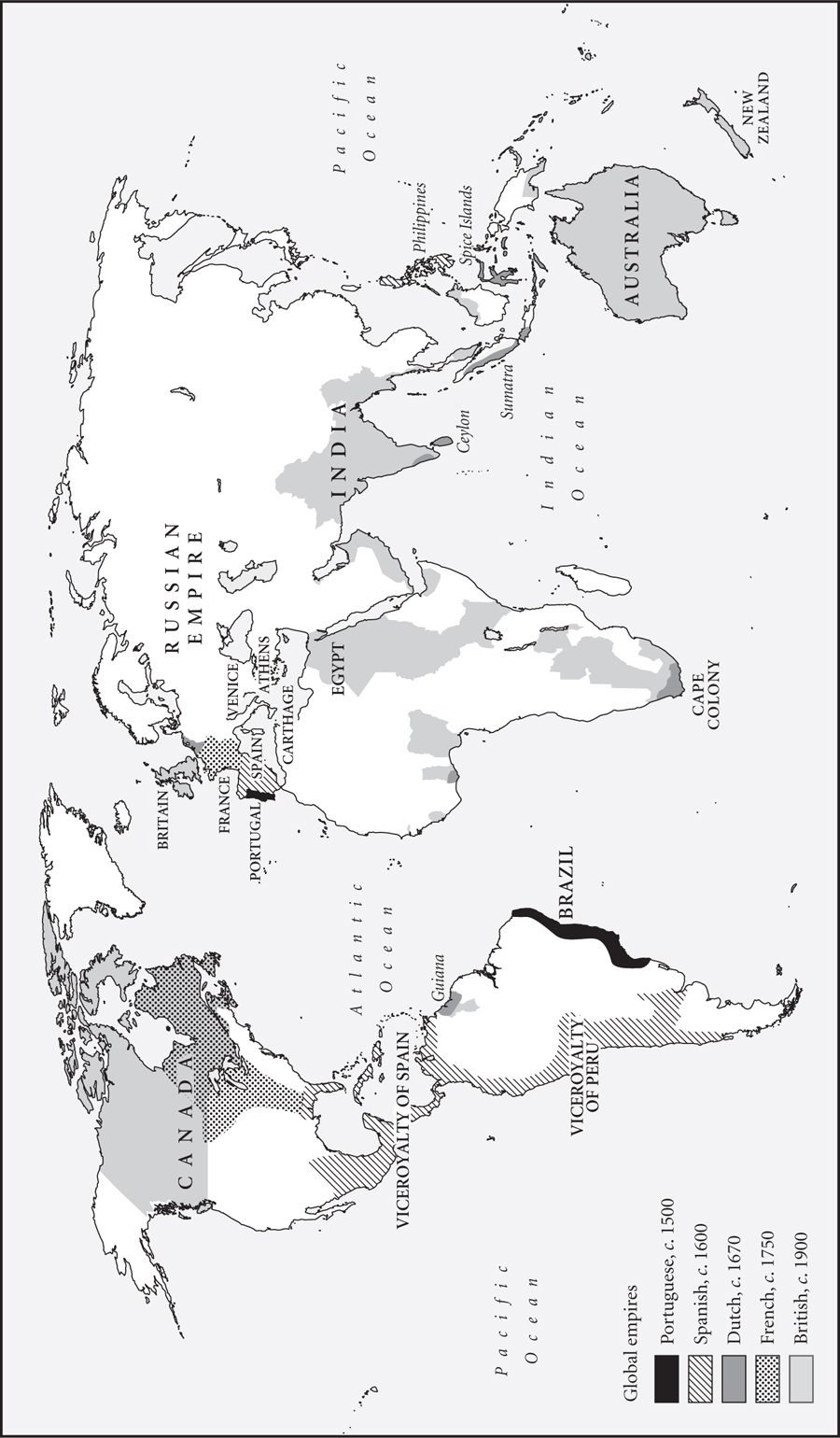

The World in the Age of Empire

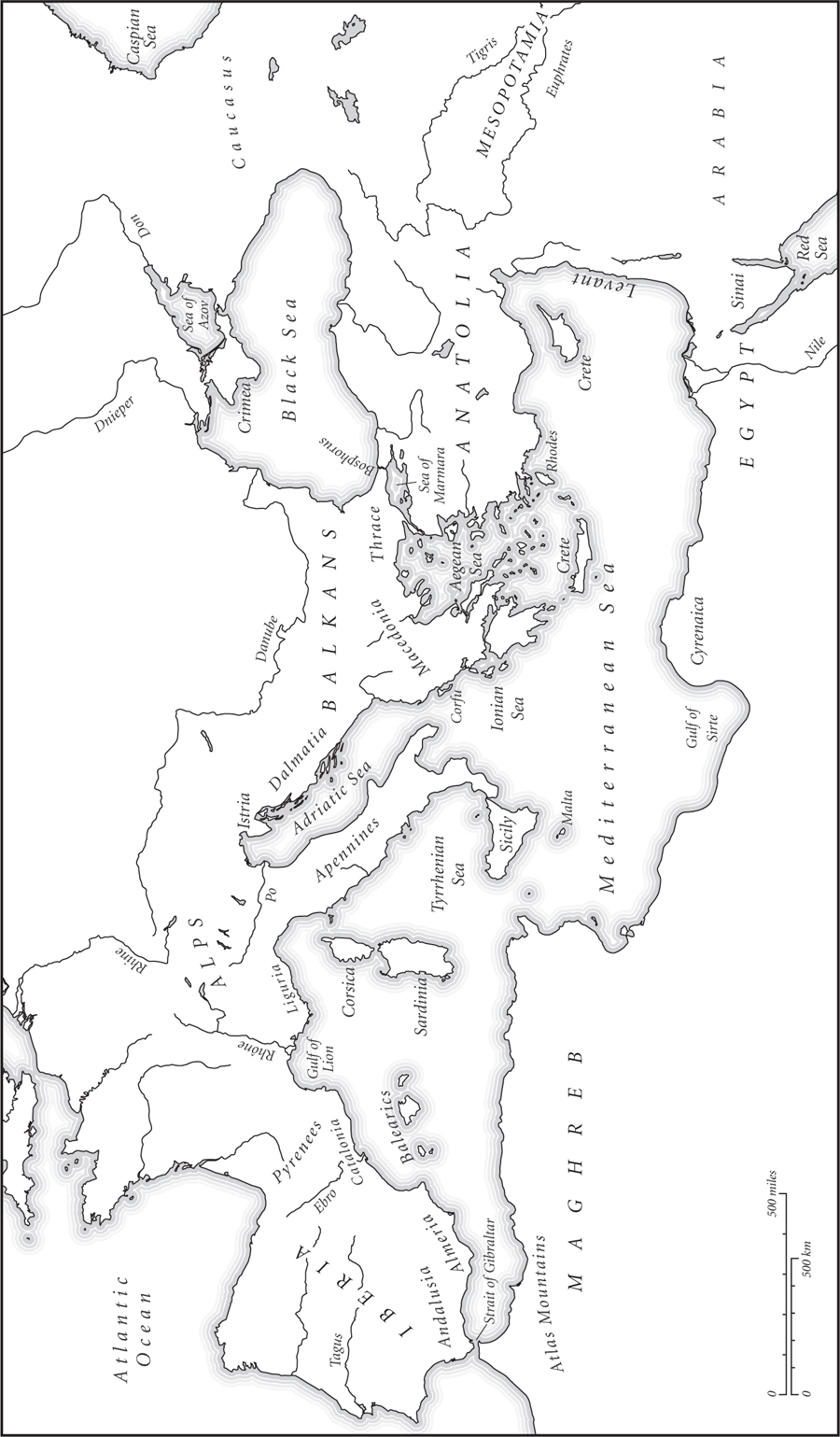

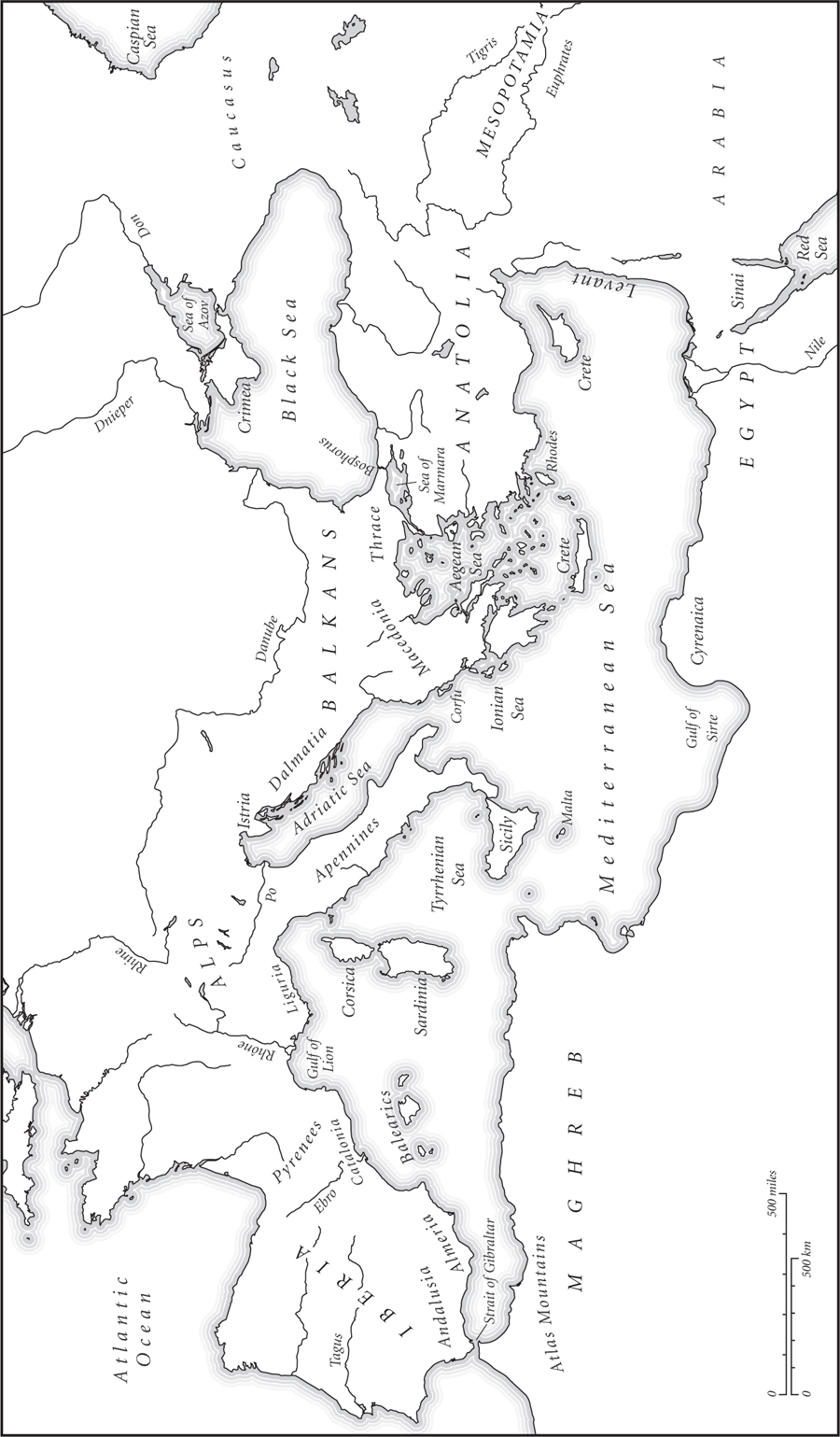

The Mediterranean

1 Celebrating the dawn of seapower: Minoan imagery like this fresco from Santorini emphasised the ships, ports and fishing that shaped the first thalassocracy.

2 Pericles, leader and theorist of the Athenian seapower state in the early years of the Peloponnesian War. His fame was cemented by Thucydides immortal history, a work that stressed the totality of such an identity, and the political problems that flowed from democracy.

Next page