Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

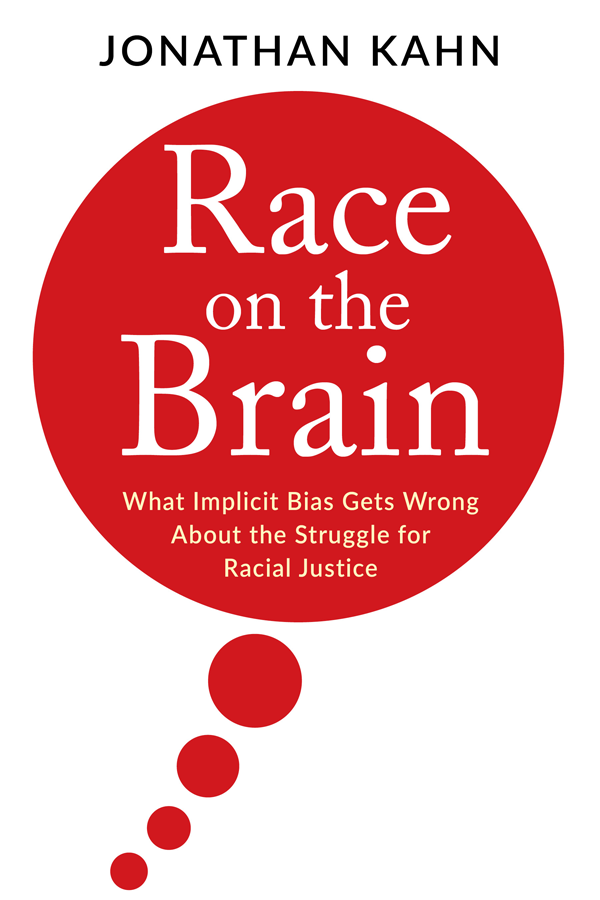

RACE ON THE BRAIN

JONATHAN KAHN

RACE ON THE BRAIN

What Implicit Bias Gets Wrong About the Struggle for Racial Justice

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS

NEW YORK

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New YorkChichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2018 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-54538-9

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Kahn, Jonathan, 1958 author.

Title: Race on the brain : what implicit bias gets wrong about the struggle for racial justice / Jonathan Kahn.

Description: New York : Columbia University Press, [2017] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017010254 | ISBN 9780231184243 (cloth : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Discrimination in criminal justice administrationUnited States. | Discrimination in justice administrationUnited States. | RacismPsychological aspects. | RacismUnited States. | DiscriminationLaw and legislationUnited States.

Classification: LCC HV9950 .K34 2017 | DDC 364.3/400973dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017010254

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

Cover design: Noah Arlow

CONTENTS

I n 2012, I came across a study out of Oxford University purporting to show that taking a particular drug (the beta blocker propranolol) could eliminate implicit bias. Where BiDil involved the problematic implications of developing a drug to treat a race, the Oxford study raised the no less troubling issue of developing a drug to treat racism. Where the former raised the specter of biologizing race, the latter biologized racism. As I began to explore the background to the Oxford study, I found it grounded in two decades of psychological and neuroscientific research on the cognitive basis of implicit biasa field of science known as implicit social cognition. This research, in turn, led me to the field of behavioral realism, where a distinct set of legal scholars and policy makers had taken up the findings of implicit social cognition to make arguments about the nature of racial bias in contemporary American society and the best ways to address it. While I was tracing the path back from pills for racism to the beginnings of behavioral realism and then forward again to the present, Ferguson erupted, the Black Lives Matter movement emerged, and the language of implicit bias suffused media discussions of policing practices in America. But the more I learned about the foundations of implicit bias and the ways it was being deployed in legal and policy contexts, the more concerned I became about how it was being used as a primary lens through which to view issues of racial justice. The idea of a pill for racism, it turned out, was merely an extreme form of what was already logically present in the racial frame created by behavioral realismthe ideal of a neat, technical fix for racism. And so what began as an article on pills for racism grew into a much larger project on constructing and contesting the common sense of racism in law, science, and society.

In order to identify and address persistent racial inequality and injustice, we must first consider how we understand the basic nature of the problem. In their pathbreaking book Racial Formation in the United States , Michael Omi and Howard Winant examine how race becomes common sensea way of comprehending, explaining or acting in the world. My book instead examines how a distinctive conception of racism has become common sense in contemporary American society. It focuses in particular on how law and science can come together to shape and inform this common sense of racism and provides an extended critique of how the idea of implicit bias is being used to understand and address issues of racial justice in contemporary American law and society. At the outset, I want to be clear that I do not deny the significance of implicit bias or the potential utility of bringing it to light. I consider many of the people engaged in exploring and promoting implicit bias research and interventions to be allies in the fight for racial justice. Nonetheless, I am deeply concerned that in many quarters implicit bias has morphed from a useful psychological theory of cognitive function into a master narrative framing legal and policy responses to race and racism in America today. As this one particular tool for understanding certain aspects of racial dynamics has grown into a dominant story of contemporary race relations, I believe it is having certain profound and problematic unintended impacts on the underlying assumptions that shape the law and policy of racial justice in America.

Foremost among these impacts are (1) the reinforcement of the logic of conservative equal-protection jurisprudence that embraces a color-blind ideal, denies the importance of history, and holds up diversity as the sole rationale for affirmative action; (2) the reduction of racism to merely another form of bias in a manner that erases the distinctive legacy and meaning of racism in the United States; (3) the obscuring of the relations of power that undergird contemporary race relations; (4) the promotion of a mirage of easy, pain-free ways to fight racism; (5) an overenthusiastic and uncritical embrace of the idea of a technological fix for what is fundamentally a complex social, political, and historical problem; and (6) an open door to the biologization of racism, which casts it as a neurological or biochemical phenomenon susceptible to biochemical interventionsthe ultimate technical fix.

My aims here, therefore, are to uncover how the discourses and technologies (both legal and scientific) of implicit bias are being deployed in ways that threaten to undermine broader progress on racial justice and to propose alternative approaches that bring implicit bias back into balance with other understandings of and approaches to racial justice.

Early on in my work on this book, I had occasion to discuss it over lunch with Troy Duster. I expressed some concern that it might seriously ruffle some feathers among my colleagues who worked on implicit bias and asked Troy if he had any advice. He simply said, Thats right. There are likely going to be some people who are unhappy with this book. At first, I thought (uncharitably) something to the effect of Thanksthat and a buck will get me a cup of coffee. Of course, as I progressed with the project, I came to realize that Troys statement, although simple, was acutely apt. As I developed my analysis of the making and unmaking of the common sense of racism in American society, I realized that one of my greatest concerns with work on implicit bias is its insistence on not ruffling feathers not making people uncomfortable with the persistence of racial injustice and racism in this country. If I do not ruffle any feathers with this book, then perhaps it is not the book it should be. Thus, Troys generous spirit and intellectual acuity have continued to inform my work throughout this project.

Along the way, many other scholars have offered critical insight and support. Foremost among them have been Osagie Obasogie and Lundy Braun, who have enthusiastically urged me to get the book out and generously offered thoughtful comments and close readings along the way. I was privileged to present an early version of the first two chapters at the workshop Race and Empirical Legal Studies at the University of Wisconsin School of Law, where I was fortunate to have Joan Fujimura offer extensive and helpful comments as a primary reader of the paper. I also presented aspects of the project at the annual meeting of the Science and Democracy Network and Duke Universitys Conference on the Present and Future of Civil Rights Movements: Race and Reform in 21st Century America; the annual meetings of the Association of Law, Medicine, and Ethics and the American Anthropological Association; and the University of California at Irvine conference Race, Biological Causation, and Science Communication. I am also grateful to Dayna Matthew for our spirited and enlightening conversations during several shared conference panels over the past few years. As in all my work on race and science over the past decade, the RaceGen listserve has provided me with a vital and supportive virtual intellectual community. As ever, Jay Kaufman and Jon Marks have been especially helpful (and diverting) colleagues within this online village. Among the many others to whom I am indebted for continuing conversation and support are Ruha Benjamin, Rina Bliss, Deborah Bolnick, Simon Cole, Martha Crossley, Duana Fullwiley, Evelynn Hammonds, Terrence Keel, Alondra Nelson, Aaron Panofsky, Kimani Paul-Emile, Dorothy Roberts, Carolyn Rouse, and Patricia Williams. As with my previous book, Patrick Fitzgerald and the staff at Columbia University Press have been wonderful to work with. Supportive and responsive, they have been exemplary partners in these endeavors. This book is for Emma, who has grown into a remarkable young woman, and for Karen-Sue, who with loving grace and equanimity shares our newly empty nest with me.