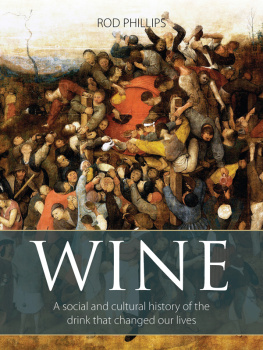

Rod Phillips is a wine writer who lives in Ottawa, Canada. He is professor of history at Carleton University, where he teaches courses on alcohol, food and European history. He has published in wine media such as The World of Fine Wine, Wine Spectator, Vines Magazine and the guildsomm.com website, and he is wine writer for NUVO Magazine. His books on wine include The Wines of Canada (in the Classic Wine Library, 2017), 9000 Years of Wine (2017), French Wine: A History (2016), Alcohol: A History (2014), and A Short History of Wine (2000). His books have been widely translated.

Copyright Roderick Phillips, 2018

The right of Roderick Phillips to be identified as the author of this book has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

First published in 2018 by

Infinite Ideas Limited

www.infideas.com

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of small passages for the purposes of criticism or review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise, except under the terms of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 or under the terms of a licence issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency Ltd, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4LP, UK, without the permission in writing of the publisher. Requests to the publisher should be emailed to the Permissions Department, .

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 9781910902479

Brand and product names are trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners.

All web addresses were checked and correct at time of going to press.

Front cover image showing detail from The Wine of Saint Martins Day by Pieter Bruegel the elder (1568) courtesy of FineArt/Alamy Stock Photo

All text photos and illustrations courtesy of the Wellcome Collection except image on page 68 courtesy Carole Reeves.

Typeset by DigiTrans Media, India

INTRODUCTION

Wine has an extraordinarily complex and rich history that extends across most of the world. It has been made on every continent, except for Antarctica, for hundreds or thousands of years. It sometimes seems, from the perspective of the early twenty-first century, that there is no place on earth that lacks a wine industry. Although there are climatic limits to the locations where sustained and successful viticulture can be practised, entrepreneurs and would-be vignerons seek out small areas with marginally suitable mesoclimates to try their hand at growing grapes and making wine. Moreover, the recent phase of climate change has shifted the boundaries long accepted as suitable for viticulture and has opened up possibilities for growing wine grapes where it used to be not only marginal but impossible. Wine is now made commercially in all states of the United States, except Alaska, and in many parts of northern Europe, including England, Ireland, and Denmark.

Climate might dictate the extent of sustained and successful wine production but the only restraints on sustained and successful wine consumption are those imposed by laws. Civil and religious authorities have historically established regulations for the production, sale, and consumption of wine. Today these limitations range widely in their forms. They include regulating wineries, setting minimum legal drinking ages, licensing bars and restaurants, controlling the hours of wine sales, and restricting the drinking of wine in public. These limitations usually apply to beer and spirits, too, of course. In some places, wine and other alcoholic beverages are not restricted but banned. A dozen Muslim-majority countries, such as Saudi Arabia, Iran, and Kuwait, prohibit the production, sale, and consumption of alcohol entirely. The Constitution of India declares that the State shall endeavour to bring about prohibition of the consumption, except for medicinal purposes, of intoxicating drinks and Prohibition is in force in three states and one territory in that country. These examples represent exceptions to the near-global reach of wine today.

Wine, then, is a nearly ubiquitous beverage, just like beer and distilled spirits and a little less so than water, tea, and coffee, and there are times when their histories intersected. For example, when coffee, tea, and chocolate (consumed initially only as a beverage) were introduced to wine- and beer-drinking Europe, there were debates as to which were more or less healthy or harmful, regardless of whether they contained alcohol or not. Water, the sole universal beverage, was for some centuries regarded as so dangerous in some parts of Europe (and later in North America) that physicians advised against drinking it and recommended rehydrating by drinking wine and beer instead.

But it is arguable that the history of wine is that much more complex because of the cultural, social, and medical values that have historically been attached to it. Stressing the richness of the history of wine is not to diminish the histories of water, tea, and coffee, or of the other alcoholic beverages. Beer, distilled spirits, cider, mead, and fruit wines have fascinating histories, and I have written about them in my general history of alcohol. I am particularly aware of the occasional tensions between beer and wine lovers. Some years ago, when I was writing a weekly wine column for Ottawas main daily newspaper, my editor asked me to write a column on beer for Canada Day, on the ground that beer was Canadas national drink. I complied, but I compared the complexity of beer unfavourably with wine, a move that generated angry letters to the editor from partisans of beer who demanded that I be fired or, at the very least, be prevented from writing about beer ever again. I responded the following week with a mea culpa , explaining that I would not have been so casually dismissive of beer had I known that beer drinkers could read.

To avoid another episode of that sort, I have tried to keep beer out of this account of wine, but it has crept in from time to time, as have distilled spirits and other alcoholic beverages. The reality is that when we discuss behaviour and attitudes as they relate to wine, we often have to bring other alcoholic beverages into the narrative. It would be misleading to pretend that wine was the only drink that had religious associations in many ancient cultures where there were beer gods, too. If wine was often in the past credited with having medicinal properties, so were beer and distilled spirits. And when we look at the ways men and women had different associations with wine, it is frequently their different associations with alcohol more generally that is at issue.

This, then, is a measured history of wine that places wine in various contexts but does not pretend that wine has been the worlds most important and history-changing commodity. There are books that, facetiously or not, place certain foods (such as potatoes) front and centre in the broad sweep of history. This is a problem common to many biographies, especially of minor figures whose importance must be inflated and distorted by their biographers simply to justify their writing about them. The history of wine needs no such manipulation. The subtitle of this book, referring to the way that wine has changed our lives might sound like a world-historical claim, but it recognizes that the readers of this book are more likely to be people engaged with wine to an extent that it has made an impact on their lives.

This has been an interesting book to write in that, unlike most histories, it is organized by theme rather than chronologically. It has made me think about wine differently, starting with the question of which themes were the most important. Some, such as health and religion, were obvious. Others, such as crime and landscape, were less so. It also brought to light the limitations of dealing with wine thematically in that it is impossible to isolate themes from one another. The medicinal properties attributed to wine are not only a matter of health, but stray into food and wine pairing in the chapter called wine and the table, and into ways of describing wine in wine and words. Similarly, the discussions of food cross over to issues of health in wine and wellness and, through the idea of terroir, into wine and landscape. Overall, though, it is a very viable way of looking at the history of wine, and it allows readers to consume the book in discrete pieces more easily than a chronological history does. Here you can start reading any chapter without missing anything.

Next page