Contents

About the Book

Why do we no longer trust experts, facts and statistics?

Why has politics become so fractious and warlike?

What caused the populist political upheavals of recent years?

How can the history of ideas help us understand our present?

In this bold and far-reaching exploration of our new political landscape, William Davies reveals how feelings have come to reshape our world. Drawing deep on history, philosophy, psychology and economics, he shows how some of the fundamental assumptions that defined the modern world have dissolved. With advances in medicine and the spread of digital and military technology, the divisions between mind and body, war and peace are no longer so clear-cut. In the murky new space between mind and body, between war and peace, lie nervous states: with all of us relying increasingly on feeling rather than fact.

In a book of profound insight and astonishing breadth, William Davies reveals the origins of this new political reality. Nervous States is a compelling and essential guide to the turbulent times we are living through.

About the Author

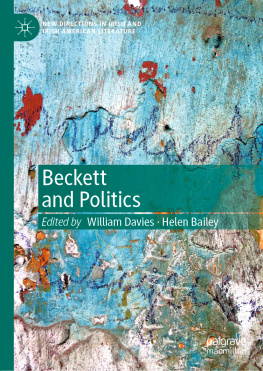

William Davies teaches political economy and sociology at Goldsmiths, University of London. His work explores the history of ideas, especially the history of economics, and how this helps us understand the present. He is the author of The Happiness Industry and The Limits of Neoliberalism, and regularly writes for the Guardian and London Review of Books.

ALSO BY WILLIAM DAVIES

The Limits of Neoliberalism

The Happiness Industry

To Martha

Introduction

On a late Friday afternoon in November 2017, police were called to Londons Oxford Circus for reasons described as terror-related. Oxford Circus Underground station was evacuated, producing a crush of people as they made for the exits. Reports circulated of shots being fired, and images and video appeared online of crowds fleeing the area, with heavily armed police officers heading in the opposite direction. Eyewitnesses described screams and chaos, with people huddling inside shops for safety.

Amidst the panic, it was unclear where exactly the threat was emanating from, or whether there might be a number of attacks going on simultaneously, as had occurred in Paris two years earlier. Armed police stormed Selfridges department store, while shoppers were instructed to evacuate the building. Inside the store at the time was the pop star Olly Murs, who tweeted to his 8 million followers Fuck everyone get out of Selfridge now gun shots!! As shoppers in the store made for the exits, others were rushing in at the same time, producing a stampede.

Smartphones and social media meant that this whole event was recorded, shared and discussed in real time. The police attempted to quell the panic using their own Twitter feed, but this was more than offset by the sense of alarm that was engulfing other observers. Former leader of the far-right English Defence League Tommy Robinson tweeted that this looks like another jihad attack in London. The Daily Mail unearthed an innocent tweet from ten days earlier, which had described a lorry stopped on a pavement in Oxford Street, and inexplicably used this as a basis on which to tweet Gunshots fired as armed police officers surrounded Oxford Circus station after lorry ploughs into pedestrians. The media was not so much reporting facts, as serving to synchronise attention and emotion across a watching public.

Around an hour after the initial evacuation of Oxford Circus, the police put out a statement that to date police have not located any trace of any suspects, evidence of shots fired or casualties. It subsequently emerged that nine people required treatment in hospital for injuries sustained in the panic, but nothing more serious had yet been discovered. A few minutes later, the London Underground authority tweeted that stations had reopened and trains were running normally. Soon after that, the emergency services were formally stood down. There were no guns and no terrorists.

What had caused this event? The police had received numerous calls from members of the public reporting gunshots on the Underground and on street level, and had arrived within six minutes ready to respond. But the only violence that anyone had witnessed with their eyes was a scuffle on an overcrowded rush-hour platform, as two men bumped into each other, and a punch or two was thrown. While it remained unclear what had caused the impression of shots being fired, the scuffle had been enough to lead the surrounding crowd to retreat suddenly in fear, producing a wave of rapid movement that was then amplified as it spread along the busy platform and through the station. Given that there had been two successful terrorist attacks in London earlier in the year and seven others reportedly foiled by the police, it is not hard to understand how panic might have spread in such confined spaces.

Ghost disturbances like this had happened before. New Yorks JFK airport had witnessed a similar occurrence the previous year. On that occasion, stampedes broke out in numerous terminals across the airport, with reports on Twitter of an active shooter on the loose. One explanation was that the crowd had started to knock over the metal poles which organise lines of passengers, and the cumulative sound of these hitting the floor resembled gunfire. A small accident or misunderstanding was rapidly exaggerated, thanks to a combination of paranoid imagination and social media.

Following the Oxford Circus incident, local shopkeepers demanded a Tokyo-style loudspeaker system to be installed in the surrounding streets to allow the police to communicate with entire crowds all at once. The idea gained little traction but did diagnose the problem. Where events are unfolding rapidly and emotions are riding high, there is a sudden absence of any authoritative perspective on reality. In the digital age, that vacuum of hard knowledge becomes rapidly filled by rumours, fantasy and guesswork, some of which is quickly twisted and exaggerated to suit a preferred narrative. Fear of violence can be just as disruptive a force as actual violence, and it can be difficult to quell once it is at large.

In statistical terms, the chance of dying in a terrorist attack or mass shooting in London or New York is extremely small indeed. But this type of cool objective perspective is not available nor particularly useful to the person who is in immediate fear for their life. After a panic has ended, it is up to political authorities, newspaper reporters and experts to try and establish the facts of what has taken place. But nobody would expect people to act in accordance with the facts in the heat of the moment, as a mass of bodies are hurtling and screaming around them. Where rapid response is essential, bodily instinct takes hold.

Events such as these typify something about the times in which we live, when speed of reaction often takes precedence over slower and more cautious assessments. As we become more attuned to real time events and media, we inevitably end up placing more trust in sensation and emotion than in evidence. Knowledge becomes more valued for its speed and impact than for its cold objectivity, and emotive falsehood often travels faster than fact. In situations of physical danger, where time is of the essence, rapid reaction makes sense. But the influence of real time data now extends well beyond matters of security. News, financial markets, friendships and work engage us in a constant flow of information, making it harder to stand back and construct a more reliable portrait of any of them. The threat lurking in this is that otherwise peaceful situations can come to feel dangerous, until eventually they really are.