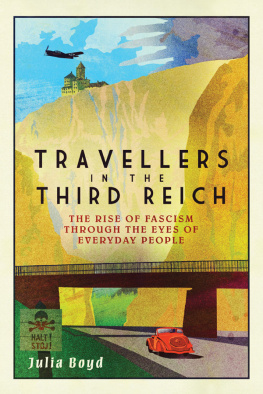

A s this long list of acknowledgements makes clear, Travellers in the Third Reich has been a collaborative effort. A book that is so dependent on fresh material relies heavily on the goodwill of a great many people. It is thanks to all those who allowed me access to private papers, and to the librarians and archivists around the world who sent me scans of documents, that this book exists.

Without Dr Piers Brendons readiness to share with me his profound knowledge of the period, the book would be very much the poorer. I owe him a great debt. Hugh Geddes not only introduced me to the letters of his aunt HRH Princess Margaret of Hesse and the Rhine, but also pointed me in many other fruitful directions. I thank him for his time, enthusiasm and especially for the friendship that resulted from our joint explorations. My dear friend Angelica Patel, who has herself written about the Nazi period, contributed an essential German perspective to the project and suggested many improvements. Dr Frances Wood not only located obscure Chinese sources but also translated them. In a wider sense she has over many years given me consistent encouragement and much wise advice. Not all academics are as generous with their time and information as Dr Bradley Hart, who was also kind enough to let me read his book George Pitt-Rivers and the Nazis before publication. Sir Brian Crowe shared with me his extensive knowledge of Germany and its history. He generously read the book in manuscript and made countless helpful suggestions. At an early stage, Dr Barbara Goward and Camilla Whitworth-Jones gave me much-needed encouragement, raising many useful points. For years Phoebe Bentinck has been a long-suffering supporter of my writing efforts. In this instance, I thank her especially for leading me to a number of important sources.

The following individuals showed great trust in allowing me to study and quote from family papers. I am deeply grateful to them all:

Viscount Astor, Brigid Battiscombe, Jonathan Benthall, Dominic Graf Bernstorff, Mary Boxall, The Hon. Lady Brooksbank, Sir Andrew Cahn, Sir Edward Cazalet, Randolph Churchill, Sebastian Clark, Miranda Corben, Sir Brian Crowe, April Crowther, Gloria Elston, Dr Richard Duncan-Jones, Francis Farmar, the late Sir Nicholas Fenn, Clare Ferguson, Diana Fortescue, Rosamond Gallant, George Gordon-Lennox, Dr Joanna Hawthorne Amick, Francis Hazeel, Rainer Christoph Friedrich Prinz von Hessen, Rachel Johnson, Jackie and Mick Laurie, Lady Rose Lauritzen, Dr Clara Lowy, Judy Kiss, Colin Mackay, Richard Matthews, Joanna Meredith-Hardy, Keith Ovenden, Jill Pellew, Charles Pemberton, Lord Ramsbotham, David Tonge, Celia Toynbee, Evelyn Westwood, Camilla Whitworth-Jones, Anne Williamson and Patricia Wilson.

I was lucky enough to meet these women, all of whom despite their advanced years retained crystal clear memories of their time in Germany during the 1930s. The late Mary Burns, Alice Frank Stock, Marjorie Lewis, Sylvia Morris, the late Hilda Padel, the late Dr Jill Poulton and The Hon. Mrs Joan Raynsford. Alice Fleet told me the remarkable story of how her parents rescued a Jewish girl, and Annette Bradshaw that of her mothers Kristallnacht experience. I thank them both for letting me use these very personal accounts.

I am fortunate to have friends like Dr Nancy Sahli and Ken Quay, who undertook extensive research for me in America. Their efforts on my behalf cost them much time and effort I am deeply grateful.

The following individuals have helped me in many and various ways. I offer heartfelt thanks to each and every one of them:

Bruce Arnold, Nicholas Barker, Professor Gordon Barrass, Ian Baxter, Lady Beecham, Professor Nigel Biggar, Embla Bjoernerem, Tony Blishen, The Hon. Lady Bonsor, Catherine Boylan, Alison Burns, Lady Burns, Sir Rodric Braithwaite, Georgina Brewis, Edmund and Joanna Capon, Joneen Casey, Professor C. C. Chan, Dr Peter Clarke, Harriet Crawley, Ronia Crisp, Lavinia Davies, Thomas Day, Professor Nicholas Deakin, Guy de Jonquires, Harriet Devlin, David Douglas, Lady Fergusson, Martin Fetherston-Godley, Dr Lucy Gaster, Sally Godley Maynard, Lord Gowrie, the late Graham Greene, Barbara Greenland, Jon Halliday, Sir Richard Heygate Bt, The Lady Holderness, Fiona Hooper, The Lady Howell, Elizabeth James, Professor James Knowlson, Beatrice Larsen, Barbara Lewington, Jeremy Lewis, Nigel Linsan Colley, Margaret Mair, Dr Philip Mansel, Jane Martineau, Christopher Masson, Charlotte Moser, Konrad Muschg, Dr Mark Nixon, Sir David Norgrove, The Dowager Marchioness of Normanby, James Peill, Matt Pilling, Dr Zoe Playdon, Catherine Porteous, David Pryce-Jones, Ambassador Kishan Rana, John Ranelagh, Clare Roskill, Nicholas Roskill, Daniel Rothschild, Lord and Lady Ryder, Professor Jane E. Schultz, Dr David Scrase, Kamalesh Sharma, William Shawcross, Michael Smyth, Dr Julia Stapleton, Dr Zara Steiner, Rupert Graf Strachwitz, Jean-Christophe Thalabard, Michael Thomas QC, Sir John and Lady (Ann) Tusa, Professor Dirk Voss, Sir David Warren, Brendan Wehrung, Patricia Wilson, Joan Winterkorn, Dalena Wright, the late Melissa Wyndham, The Lady Young and Louisa Young.

I want to thank the following archivists and librarians who went well beyond the call of duty to provide copies of documents or to help me in numerous other ways:

Carlos D. Acosta-Ponce, Elaine Ardia, Julia Aries, Pamela Bliss, Bodil Borset, Lorraine Bourke, Jacqueline Brown, Christine Colburn, Mary Craudereuff, Kelly Cummins, Jayne Dunlop, Deborah Dunn, Angie Edwards, Jenny Fichmann, Susanna Fout, Neil French, Maggie Grossman, Alison Haas, Amy Hague, Ellie Jones, Christopher Kilbracken, Dr Martin Krger, Brett Langston, Aaron Lisec, Dr Rainer Maas, Evan McGonagill, Duncan McLaren, Diana McRae, A. Meredith, Michael Meredith, Dr A. Munton, Patricia C. ODonnell, Janet Olsen, Robert Preece, Carrie Reed, Susan Riggs, Andrew Riley, Steve Robinson, Emily Roehl, Dr Ingo Runde, Sabin Schafferdt, Florian Schreiber, Helge W. Schwarz, Wilfried Schwarz, Dr Joshua Seufert, Adrienne Sharpe, Paul Smith, Angela Stanford, Sandra Stelts, James Stimpert, Rachel Swanston, Susan Thomas, Kristina Unger, Debbie Usher, Anna van Raaphorst, Nathan Waddell, Katharina Waldhauser, Melinda Wallington, Jessica West, Madison White and Jocelyn Wilk.

I owe special thanks to Allen Packwood, director of the Churchill Archives Centre at Churchill College, Cambridge, and his exceptional team; to Spencer Howard of the Herbert Hoover Presidential Library; and to Andrew Lownie, my agent, who suggested the subject in the first place. Working with Jennie Condell and her team at Elliott & Thompson has been pure pleasure.

I am also deeply grateful to Zita Freitas, who has kept our household running for thirty years. Without her support I would be lost.

Lastly, I want to thank my very own live-in editor, translator, adviser, travelling companion and patient listener my husband, John.

over the Treaty of Versailles or simply the memory of a good German holiday Many foreign visitors felt that it was not their business to comment on Germanys internal affairs, while many more were simply not interested.

But as the years passed, it became increasingly difficult for foreigners to remain agnostic. In the face of such events as the 1935 Nuremberg Laws (which deprived Jews of their citizenship), earlier assurances from moderate Germans that the Nazis would in time settle down and become civilised began to look utterly implausible. Foreigners were now either horrified by the ever-expanding catalogue of Nazi atrocities or impressed by the equally long list of so-called achievements. By the mid-1930s most visitors, even before they arrived, had made up their minds as to which camp they belonged. It is easy enough to see why those on the far right were drawn to Nazi Germany and why those on the left stayed away. Of more interest are the visitors who despised the Nazis but continued to love and admire Germany. Many in this category had travelled or studied in the country before the First World War and had found the experience transformative. It is not difficult to understand why. Even more enticing than Germanys physical beauty was its extraordinarily rich cultural and academic tradition one that despite the First World War continued to play a key role in British and American intellectual life. The war had created despair among Germanophiles not only because of the human tragedy but because it had cut them off from such a significant part of their own lives. It was not that they were insensitive to Nazi horrors but they clung to the hope that Hitler would quickly fade and their Germany the real Germany would re-emerge in all its cultural glory. Others, who like Sir Thomas Beecham were in a position to make a public protest, ducked the opportunity because the professional rewards offered by Nazi Germany were in the end too tempting. In this respect, the American writer Thomas Wolfe emerges as a true hero.

Next page