Fascism and the Right in Europe, 19191945

SEMINAR STUDIES | IN HISTORY |

Fascism and the Right in Europe, 19191945

MARTIN BLINKHORN

First published 2000 by Pearson Education Limited

Published 2013 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New-York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 2000, Taylor & Francis

The right of Martin Blinkhorn to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now lmom or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notices

Knowledge and best practice in this field are constantly changing. As new research and experience broaden our understanding, changes in research methods, professional practices, or medical treatment may become necessaly

Practitioners and researchers must always rely on their own experience and knowledge in evaluating and using any information, methods, compounds, or experiments described herein In using such information or methods they should be mindful of their own safety and the safety of others, including parties for whom they have a professional responsibility

To the fullest extent of the law, neither the Publisher nor the authors, contributors, or editors, assume any liability for any injury and/or damage to persons or property as a matter of products liability, negligence or otherw-ise, or from any use or operation of any methods, products, instructions, or ideas contained in the material herein.

ISBN 13 978-0-582-07021-9 (pbk)

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is

available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

Set by 7 in 10112 Sabon Roman

For Irene

INTRODUCTION TO THE SERIES

Such is the pace of historical enquiry in the modern world that there is an ever-widening gap between the specialist article or monograph, incorporating the results of current research, and general surveys, which inevitably become out of date. Seminar Studies in History is designed to bridge this gap. The series was founded by Patrick Richardson in 1966 and his aim was to cover major themes in British, European and world history. Between 1980 and 1996 Roger Lockyer continued his work, before handing the editorship over to Clive Emsley and Gordon Martel. Clive Emsley is Professor of History at the Open University, while Gordon Martel is Professor of International History at the University of Northern British Columbia, Canada, and Senior Research Fellow at De Montfort University.

All the books are written by experts in their field who are not only familiar with the latest research but have often contributed to it. They are frequently revised, in order to take account of new information and interpretations. They provide a selection of documents to illustrate major themes and provoke discussion, and also a guide to further reading. The aim of Seminar Studies in History is to clarify complex issues without over-simplifying them, and to stimulate readers into deepening their knowledge and understanding of major themes and topics.

NOTE ON REFERENCING SYSTEM

Readers should note that numbers in square brackets [] refer them to the corresponding entry in the Bibliography at the end of the book (specific page numbers are given in italics). A number in square brackets preceded by Doc. [Doc. 5] refers readers to the corresponding item in the Documents section which follows the main text.

AUTHORS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I should like to express my gratitude to the many Lancaster University history students, both undergraduates and postgraduates, whose work over three decades has contributed so much to my understanding of, and views on, the matters discussed in this book; to the staff of the Lancaster University Library for their unfailing helpfulness; and to the Seminar Studies editors and the Longman editorial staff for their care, professionalism and patience.

PUBLISHERS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are indebted to the following for permission to reproduce copyright material: Mary Evans Picture Library for the eight black and white plates.

Map 1 Mussolini looks up to Hitler. The Fhrers visit to the Duce

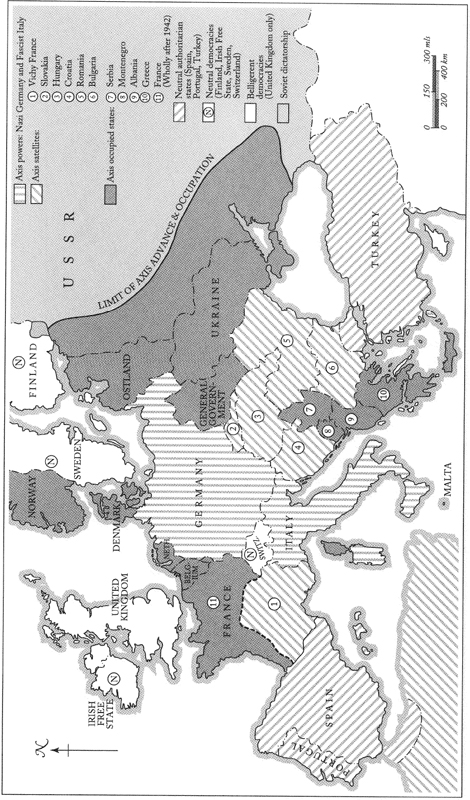

Map 2 Europe, 194142

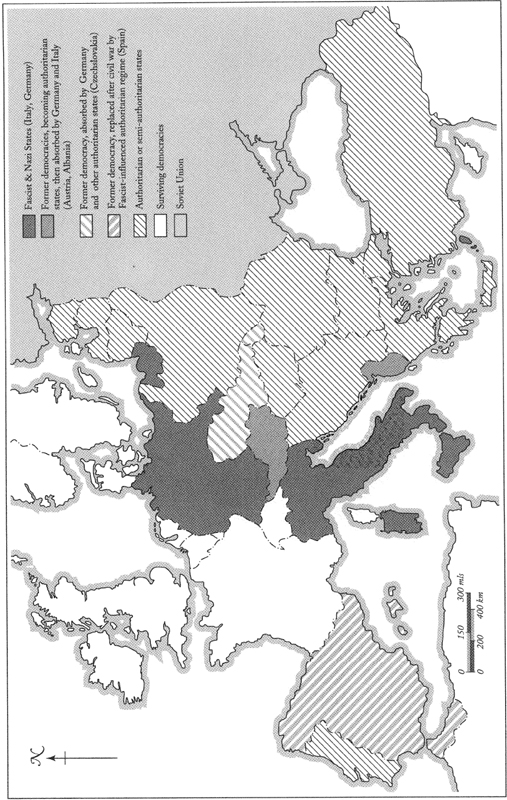

Let us begin by imagining three political maps of Europe. The first bears the caption January 1920, immediately following the promulgation of the Versailles Treaty and some months after the overthrow of short-lived Soviet regimes in Hungary and Bavaria. The second is dated Summer 1939, a few weeks before the outbreak of the Second World War in Europe. The third is labelled Winter 194142, showing the continent at the peak of Nazi Germanys European hegemony. On all three maps, each country is coloured according to its official constitutional status: communist states red, constitutional democracies white, and right-wing dictatorships black. Looking at the first map, we immediately see that west of the red of Soviet Russia, and perhaps with the exception of a decidedly grey Hungary, Europe is completely white. The second map, however, presents a very different picture: the Soviet Union is still of course red, but the white area has retreated to roughly the northwestern quadrant: France, Switzerland, the Benelux countries, the Nordic countries (including Finland and Iceland), Britain and Ireland. The rest of Europe stands out as black. Portugal, Spain, Italy, Germany, Austria, dismembered Czechoslovakia, Poland, the three Baltic states, Hungary, Yugoslavia, Romania, Bulgaria, Albania and Greece are all now subject to one or another form of right-wing authoritarian regime. Moving our gaze finally to the third map, we see that now only Britain, Ireland, Iceland, Sweden, Finland and Switzerland remain as white islands in a vast blackness whose eastern boundaries, furthermore, have been pushed hundreds of miles into the otherwise still stubbornly red Soviet Union.

Clearly, Europe between 1919 and the middle of the Second World War witnessed a broad historical process whereby the liberal democracies of the immediate post-1919 period were challenged, and in many cases overturned, by what for the moment we may loosely call right-wing forces. Moreover, and as the second of our three maps showed us, most of this process occurred before the outbreak of war in 1939, even if German arms then carried it further. In part because the first truly dramatic example of this tendency (though not actually the very first) called itself fascism, and because Fascist Italy then attracted enormous interest and publicity throughout Europe and the wider world, that term came at the time to be loosely applied to many other right-wing movements and regimes, and indeed has sometimes been applied to the whole interwar period: the so-called era of fascism. Contemporary observers of left-wing or liberal persuasion can scarcely be condemned for seeing all or most of the right-wing ideas, movements and regimes of their day, however they might differ in detail, as members of one family; all appeared hostile to representative democracy, free trade unionism, and the essential liberal freedoms of speech, publication, movement and assembly, while under all such fascist regimes, not only were free institutions suppressed but also those who upheld them were liable to be persecuted.