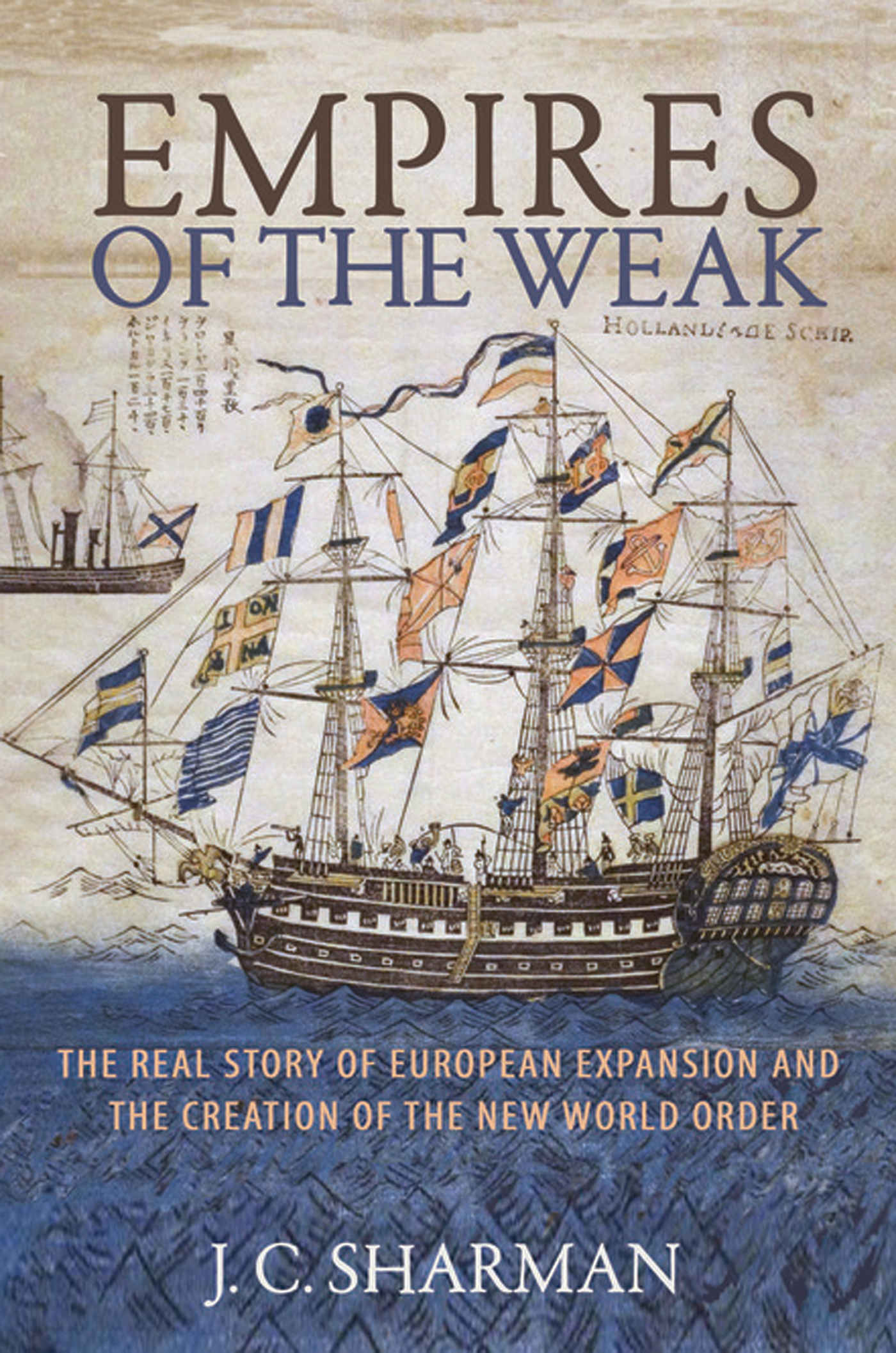

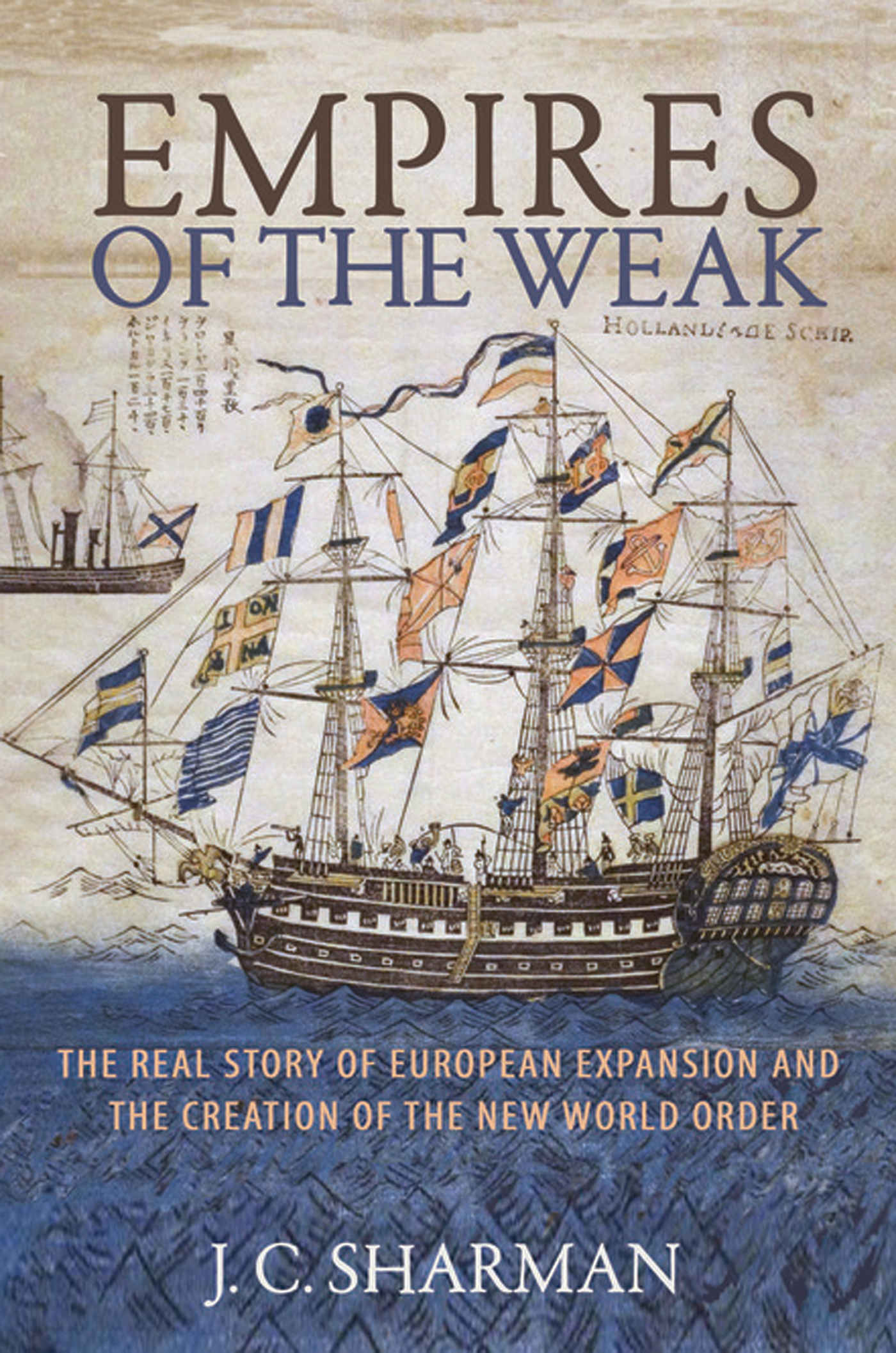

EMPIRES OF THE WEAK

Empires of the Weak

THE REAL STORY OF EUROPEAN EXPANSION AND THE CREATION OF THE NEW WORLD ORDER

J. C. Sharman

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON & OXFORD

Copyright 2019 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TR

press.princeton.edu

All Rights Reserved

LCCN 2018940067

ISBN 978-0-691-18279-7

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

Editorial: Sarah Caro and Hannah Paul

Production Editorial: Debbie Tegarden

Jacket Design: Lorraine Betz Doneker

Jacket credit: Color woodblock depicting a Dutch ship of the Dutch East India Company, c. 1860. World History Archive / Alamy Stock Photo

Production: Jacquie Poirier

Publicity: Tayler Lord

Copyeditor: Jay Boggis

This book has been composed in Miller

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Dedicated to my family and Bilyana

CONTENTS

PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

ONE OF THE GREAT pleasures of writing this book has been the opportunity to roam around considering historical questions that are fundamental to how we think about politics past, present, and future. The really big changes in international politics have little to do with the European major coalition wars that are often the staple of International Relations textbooks and scholarship. These wars have basically upheld the status quo of a fragmented Europe with a slowly changing cast of great powers (great by parochial European standards, if not always by more cosmopolitan global ones). So when it comes to transformations of international politics, perhaps it would be true to say that nothing interesting has happened in Europe for at least the last 500 years, perhaps even since the fall of the Roman Empire.

For the shifts that have fundamentally altered international politics we have to look elsewhere. Prominent amongst these transformations is first the creation of a global international system and the accompanying multi-civilizational order, second the briefer but vitally important period of European imperial world dominance for around a hundred years or so, and finally the even shorter span that saw decolonization and the return of Asian great powers. I am mainly concerned with the first of these topics, the creation of the first global international system. Dating roughly from the end of the fifteenth century to the end of the eighteenth century, this centers on a process of European expansion that helped to knit together previously separate regional systems.

Its important not to read European expansion as synonymous with European conquest or empire. Instead, in Africa and Asia, the process of expansion owed much more to European submission than dominance. Particularly when they encountered Eastern empires far mightier than any European great power of the day, Europeans had little choice but to pay deference. Though they were quick to use violence whenever they thought they could get away with it, more important than military prowess in explaining expansion was the coincidence whereby Europeans goals were largely maritimetrade routes and port outpostswhereas local great powers were concerned with controlling land and territory, but largely indifferent to the seas. These complementary preferences allowed for a rough- and-ready coexistence. In addition, European ventures in the East and the Atlantic world were crucially reliant on the cultivation of local allies, patrons, and vassals. Finally, in the Americas, various pandemics allowed European adventurers to destroy local empires, though these well-known triumphs were balanced by lesser-known defeats. In the early modern period right through to the present, changes in military and political institutions across civilizations proceeded according to cultural prompts, largely independent of functional concerns about effectiveness and efficiency.

In making and backing these claims, relating to a huge range of times and places, this book either had to be very long or quite short. The reason for writing a short book is the hope of appealing to a somewhat wider audience inside and outside of academia that might not usually be much interested in history, and perhaps a few people who might not ordinarily read social science. But if there are benefits to a short book for both the author and the readers, its only fair to acknowledge that there are serious costs as well.

The main penalty is the lack of room to really dig into and discuss all the brilliant work relevant to the topic that has informed my thinking. In getting feedback from various generous colleagues and three anonymous reviewers (of whom more below), a recurrent theme was that there are so many other authors, theories, and debates that could and should receive more attention in the text. These commentators are right: there are many authors, theories, and debates that could and should have received more attention (or even a mention). But by and large they havent. Its very important to stress that this is not a sign of disrespect or disagreement with either the original authors, or those providing comments. Nor is it an effort to overstate the originality of this book by slighting the work I build on. Instead, it reflects a calculation that research, writing, and many other things are based on trade-offs, and that the cost of neglecting vast reams of earlier scholarship is nevertheless justified in having a shorter and more accessible book.

Although this book is less concerned with immersing the reader in existing scholarship, it is in part an attempt to gently nudge (rather than hector) us to think a bit harder about how Eurocentric we still are, and what this costs us. No doubt all right-minded, good-thinking people already agree that Eurocentrism in the abstract is a bad thing. But to see how much the problem is still with us one only has to look at the table of contents or indexes of most books on international politics and history to see the extraordinary predominance of European places, actors, and events, relative to the rest of the world. This book has some of the same bias, but I hope to a lesser degree.

If I have flagrantly disregarded much of the wise advice I received about including a more detailed literature review, it remains true that many of the key elements of my argument here I owe to those who were kind enough to comment on draft text or oral presentations. I was particularly lucky to begin the project at one very stimulating and supportive academic environment, Griffith University, and finish it at a very similar institution, Cambridge University. I thus had two sets of colleagues to exploit.

At the early stages in Brisbane, Sarah Percy and especially Ian Hall gave me crucial steers on what was wrong with my first cut at the project and, even better, how I might go about fixing it. I presented initial versions at Griffith, the Australian National University, and a little later at my current departmental home, Politics and International Studies in Cambridge, and the European International Studies Association. Some of these meetings have featured formal discussants who went well above and beyond their rather thankless mandate in working hard to understand and improve my rough drafts, and so thanks in particular to Daniel Nexon, Sean Fleming, and Alex Wiesinger. Similarly selfless was the commitment of the three anonymous reviewers of the draft manuscript; it was a privilege to have my ideas receive such careful and constructive treatment. Andrew Phillips taught me a lot about how to do this kind of research in various discussions over the years, some directly related to this book, others only tangentially. At Cambridge the Department and the History & International Relations group, organized by Maja Spanu and Or Rosenboim, has provided the perfect setting for bringing this research to completion. In Cambridge and in London, Aye Zarakol, Duncan Bell, and George Lawson further helped me think through some big historical International Relations questions. I am also very grateful to David Runciman for providing the first link with Princeton University Press. At the Press, Sarah Caro performed an invaluable role in shepherding the manuscript through to acceptance and completion.

Next page