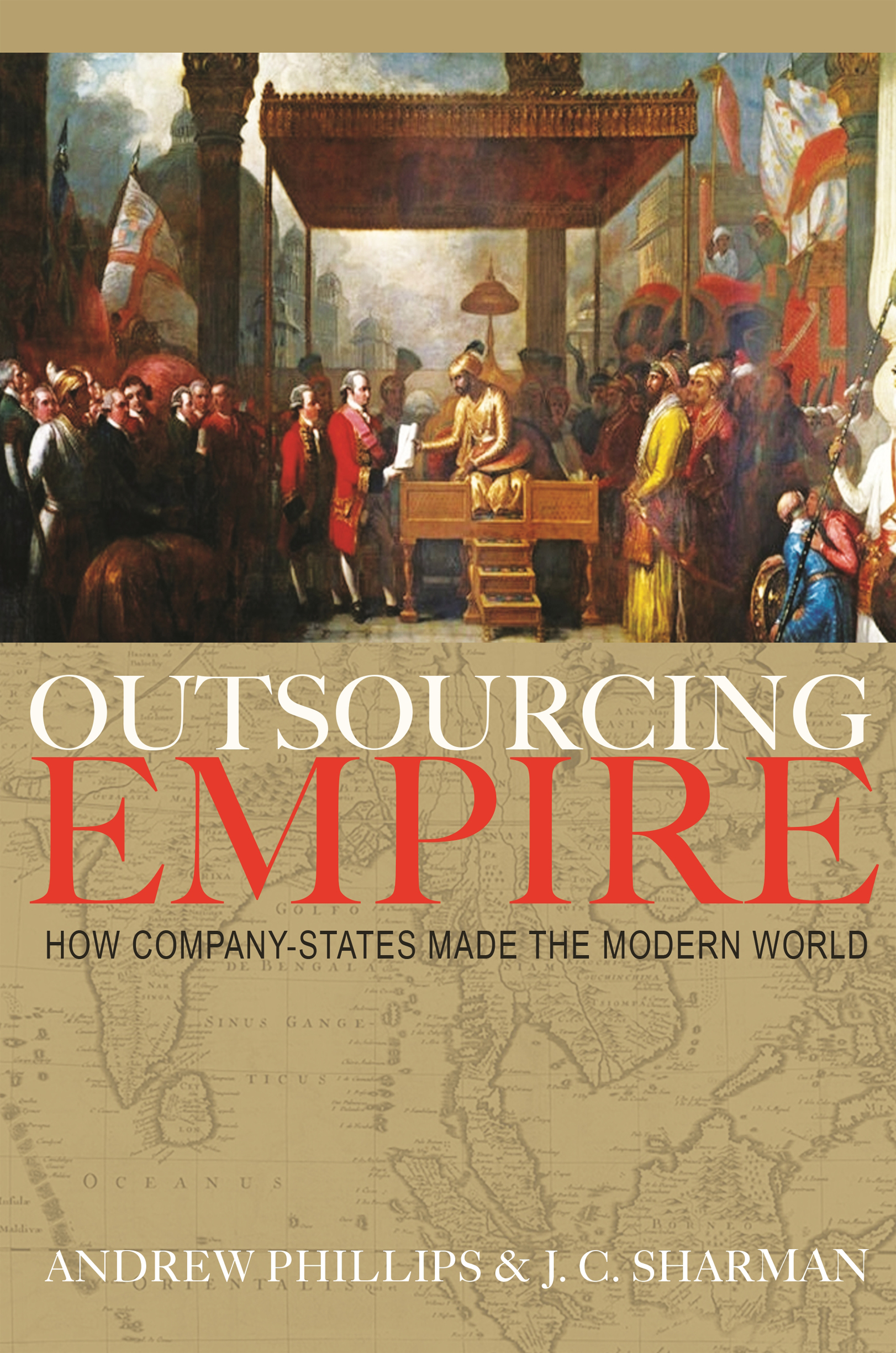

OUTSOURCING EMPIRE

Outsourcing Empire

HOW COMPANY-STATES MADE THE MODERN WORLD

Andrew Phillips and J. C. Sharman

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON AND OXFORD

Copyright 2020 by Andrew Phillips and J. C. Sharman

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to permissions@press.princeton.edu

Published by Princeton University Press

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TR

press.princeton.edu

All Rights Reserved

ISBN 978-0-691-20351-5

ISBN (pbk.) 978-0-691-20619-6

ISBN (e-book) 978-0-691-20620-2

Library of Congress Control Number: 2020934560

Version 1.0

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

Editorial: Sarah Caro, Hannah Paul, and Josh Drake

Production Editorial: Karen Carter

Jacket/Cover Design: Lorraine Doneker

Production: Erin Suydam

Publicity: James Schneider and Kate Farquhar-Thomson

Copyeditor: Erin Hartshorn

Jacket art: Benjamin West, Shah Alam, Mughal Emperor, Conveying the Grant of the Diwani to Lord Clive, 1774 British Library

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

WE BEGAN THIS BOOK while visiting the Centre for International Studies at the London School of Economics in the autumn of 2015, a visit made possible by Kirsten Ainley and George Lawson, who went well above and beyond both in their hospitality and their intellectual engagement with the project, at that time and since. Sharman also thanks Jeff Chwieroth for helping to make the visit possible. Our first public presentation of the project in the same year was at the School of Oriental and African Studies, generously hosted by Meera Sabaratnam.

Sharman is very grateful for feedback and support from colleagues at Griffith University during his time there until the end of 2016, especially from Ian Hall and Pat Weller. From 2017 the blend of International Relations and history expertise in Cambridge has made the Department of Politics and International Studies the perfect environment for thinking about and working on this project. In particular, Mette Eilstrup-Sangiovanni, Brendan Simms, and Ed Cavanagh provided very helpful corrections and pointers. More broadly, fellow Brisbane-to-Cambridge transplant Maja Spanu has been tireless in building a community of like-minded scholars in historical International Relations, a community that has had an important influence in shaping this book, and here particular thanks also to Ayse Zarakol and Duncan Bell. The Lauterpacht Centre for International Law also hosted a very positive session on the draft argument, thanks here to Sharmans Kings College colleagues Megan Donaldson and Surabhi Ranganathan.

Later in the project Sharman was invited to the present the argument at the Minnesota International Relations Colloquium, and thanks to Nisha Fazal, Pedro Accorsi Amaral, Nicauris Heredia Rosario, and Carly Potz-Nielsen for both their hospitality and comments on the project.

Over the years Hendrik Spruyt and Jesse Dillon Savage have been very discerning sounding-boards for many of the ideas that have gone into the book. Jon Pevehouse was kind enough to give us a good deal of considered feedback on a shorter version of our argument.

Phillips thanks his colleagues at the School of Political Science and International Studies at the University of Queensland for their insightful and constructive critical feedback over several years as the books argument evolved through successive iterations. Special thanks are due to the participants of the St. Lucys History and Theory reading group and to Chris Reus-Smit especially for his continued mentorship and championing of International Relations scholarship working at the nexus of theory and history.

Scholarship depends on the selflessness of peer reviewers, and we were very fortunate to have two anonymous reviewers who spent a lot of time and effort in thoughtfully reading and responding to the draft manuscript in full. Thanks also to our incredibly professional indexer Dave Prout.

Kye Allen provided fantastic research assistance in sharpening the text and the bibliography; we could not have asked for more here.

We also acknowledge the Australian Research Council for crucial financial support through Discovery Project grant DP170101395.

At Princeton University Press thanks are due to Sarah Caro and Hannah Paul. We would also like to thank our agent James Pullen for his crucial support and advocacy.

Finally, Sharman thanks Bilyana for her steadfast support and general calming effect, all the more appreciated during and in the wake of the big move. Phillips thanks his mother and father for their love and support, as well as his surrogate Brisbane familyDaniel Celm and Sophie Devitt, and Joseph and Juliet Celm.

OUTSOURCING EMPIRE

Introducing the Company-State

SOME OF THE most important actors in the crucial formative stages of the modern international system were neither states nor merchant companies, but hybrid entities representing a combination of both. For almost two centuries, company-states like the English and Dutch East India Companies and the Hudsons Bay Company combined spectacular success in amassing power and profit in driving the first wave of globalization. They were the forerunners of the modern day multinational corporation, but were at the same time endowed with extensive sovereign powers, formidable armies and navies, and practical independence. In some cases, company-states came to wield more military and political power than many monarchs of the day, as they exercised corporate sovereignty over vast territories and millions of subjects. The company-states were thus both engines of imperialism and engines of capitalism. Here we seek to explain the rise, fall, and significance of these hugely important yet often neglected actors in creating the first truly global international system.

To understand the creation of the modern international system we need a comparative study of the company-states. Yet such a study has been missing. Today we see rule, governing, and war as synonymous with states. But European states largely stood aloof from the initial wave of Western expansion that first made it possible to think of politics, economics, and many other forms of interaction as occurring on a global scale. As agents of exchange, company-states transformed the world through the inter-continental arbitrage of commodities, people, and ideas. A key theme of this book is that these actors were the primary mediators linking Europe with the rest of the world. Similarly, many European states were surprisingly reticent during the new imperialism of the late nineteenth century to directly assume the responsibilities of overseas expansion. Instead, of all the strategies and institutional expedients Europeans used to bring the rest of world under their sway from the seventeenth to the twentieth centuries, none was more common and consequential than that of the company-state. After initial spectacular successes, this form quickly became generic, being widely copied among diverse European states, from Scotland to Russia. Company-states dominated vast swathes of Asia and North America for more than a century, while also acting as the vanguard of European imperialism in Africa, much of the rest of the Americas, and in the South Pacific. While some company-states went on to great fame and fortune, many others were ignominious failures. Even now that company-states have gone, their legacies live on from Alaska to Zimbabwe.