Copyright 2019 by Mary L. Gray and Siddharth Suri

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to or to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 3 Park Avenue, 19th Floor, New York, New York 10016.

Maps Gregory T. Minton. Used with permission. All rights reserved.

Ming Yin, Mary L. Gray, Siddharth Suri, and Jennifer Wortman Vaughan. The Communication Network Within the Crowd. In Proceedings of the 25th International Conference on World Wide Web, WWW 16, pages 12931303, Republic and Canton of Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. International World Wide Web Conference Committee. Used with permission. All rights reserved.

Sara Constance Kingsley, Mary L. Gray, and Siddharth Suri. Accounting for Market Frictions and Power Asymmetries in Online Labor Markets. Policy & Internet, 7(4):383400, 2015. 2015 Policy Studies Organization. Used with permission by Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

All rights reserved.

hmhbooks.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Gray, Mary L., author. | Suri, Siddharth, author.

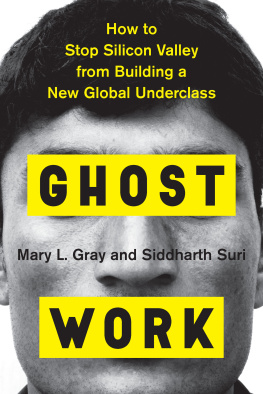

Title: Ghost work : how to stop Silicon Valley from building a new global underclass / Mary L. Gray and Siddharth Suri.

Description: Boston : Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2019. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018042557 (print) | LCCN 2018044155 (ebook) | ISBN 9781328566287 (ebook) | ISBN 9781328566249 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780358120575 (int. ed.)

Subjects: LCSH: Labor supplyEffect of automation on. | AutomationEconomic aspects. | Artificial intelligenceEconomic aspects. | Technological unemployment.

Classification: LCC HD6331 (ebook) | LCC HD6331 .G826 2019 (print) | DDC 331.1dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018042557

Cover design by Mark R. Robinson

Cover image WIN-Initiative / Getty Images

Gray photograph Adrianne Mathiowetz Photography

Suri photograph Peter Hurley

v1.0419

For Ila and George

M.L.G.

To my family and in loving memory of my dad

S.S.

Introduction

Ghosts in the Machine

The human labor powering many mobile phone apps, websites, and artificial intelligence systems can be hard to seein fact, its often intentionally hidden. We call this opaque world of employment ghost work. Think about the last time you searched for something on the web. Maybe you were looking for a trending news topic, an update on your favorite team, or fresh celebrity gossip. Ever wonder why the images and links that the search engine returned didnt contain adult content or completely random results? After all, every business, illicit or legitimate, advertising online would love to have its site ranked higher in your web search. Or think about the last time you scrolled through your Facebook, Instagram, or Twitter feed. How do those sites enforce their no-graphic-violence and no-hate-speech policies? On the internet, anyone can say anything, and, given the chance, people certainly will. So how do we get such a sanitized view? The answer is people and software working together to deliver seemingly automated services to customers like you and me.

Beyond some basic decisions, todays artificial intelligence cant function without humans in the loop. Whether its delivering a relevant newsfeed or carrying out a complicated texted-in pizza order, when the artificial intelligence (AI) trips up or cant finish the job, thousands of businesses call on people to quietly complete the project. This new digital assembly line aggregates the collective input of distributed workers, ships pieces of projects rather than products, and operates across a host of economic sectors at all times of the day and night. In fact, the rise of this shadow workforce is part of a larger, more profound reorganization of employment itself. This yet-to-be-classified form of employment done on demand is neither inherently good nor bad. But left without definition and veiled from consumers who benefit from it, these jobs can easily slip into ghost work.

Businesses can collect projects from thousands of workers, paid by the task. Now they can depend on internet access, cloud computing, sophisticated databases, and the engineering technique of human computationpeople working in concert with AIsto loop humans into completing projects that are otherwise beyond the ability of software alone. This fusion of code and human smarts is growing fast. According to the Pew Research Centers 2016 report Gig Work, Online Selling and Home Sharing, roughly 20 million U.S. adults earned money completing tasks distributed on demand the previous year. Left unchecked, the combination of ghost works opaque employment practices and the shibboleth of an all-powerful artificial intelligence could render the labor of hundreds of millions of people invisible.

Who does this kind of work? People like Joan and Kala.

Joan works from the Houston home she shares with her 81-year-old mother. In 2012, Joan moved in to care for her mother after a knee surgery left her mom too frail to live on her own. A year later, Joan started picking up work online through MTurkshort for Amazon Mechanical Turk, a sprawling marketplace owned and operated by tech giant Amazon.com. Joan makes some of her best money doing dollars for dick pics. Thats how she describes labeling pictures flagged as offensive by social media users on platforms like Twitter and Match.com.

Companies cant automatically process every piece of content users worth of such tasks.

Thousands of miles away in Bangalore, India, Kala works from her makeshift home office, tucked away in the corner of her bedroom. Joan and Kala do similar tasks, sorting and tagging words and images for internet companies, but Kala picks up work from an outsourcing company that supplies staff to the Universal Human Relevance System (UHRS), an MTurk-like platform used internally by its builder, Microsoft. Kala, a 43-year-old housewife and mother of two with a bachelors degree in electrical engineering, calls her two teenage sons into the room, points to a word displayed inside a large text box on her LED monitor, and asks them, Do you know what this word means? Is it something you shouldnt say? They giggle as she reads the text out loud to them. They make fun of her pronunciation of chick flick. Together they decide that, no, this sentence does not contain adult content. Kala clicks no on the screen, and the window refreshes with a new text phrase to read to her sons. They are more qualified to recognize these words than me, she says, laughing. They help me keep the internet clean and safe for other families. Though shes typically unable to find enough tasks to fill more than 15 hours of work in a given week, Kala returns to UHRS almost every day to see if there are any new tasks that she feels qualified to do. Kalas doggedness and luck in the past have paid off. Now that shes learned how to browse and claim tasks quickly, Kala can make the time she has between making meals and checking her childrens homework feel, as she puts it, fruitful as she does web research for what she considers extra income.

Content moderationfrom sifting through newsfeeds and search results to adjudicating disputes over appropriate content to help technology and media companies figure out what to leave up or take downis just one example of a new type of work that depends on people like Joan and Kala. Reviewing content is a common, often time-sensitive task generated in the wake of social media companies attempts to identify family-friendly materials for the billions of people who use their sites every day. There are way too many webpages, photos, and tweets in every imaginable language for people like Joan and Kala to assess them all.