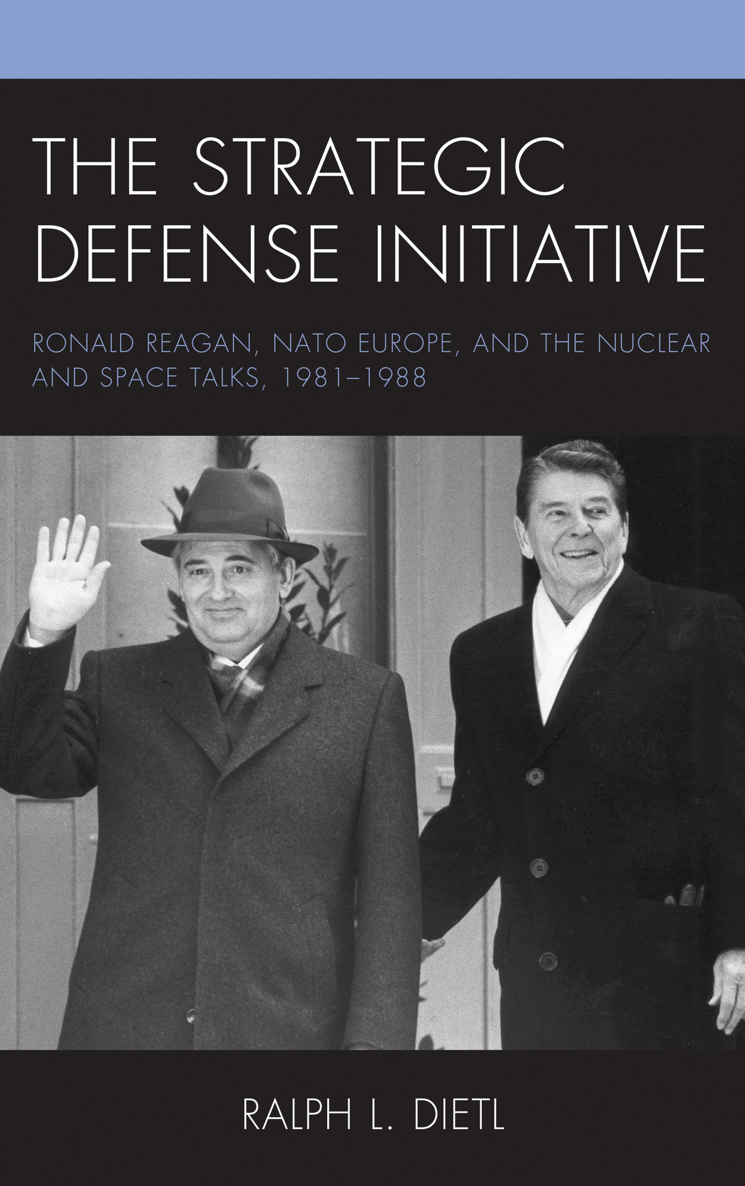

The Strategic Defense Initiative

The Strategic Defense Initiative

Ronald Reagan, NATO Europe, and the Nuclear and Space Talks, 19811988

Ralph L. Dietl

LEXINGTON BOOKS

Lanham Boulder New York London

Published by Lexington Books

An imprint of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706

www.rowman.com

Unit A, Whitacre Mews, 26-34 Stannary Street, London SE11 4AB

Copyright 2018 by The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Available

LCCN 2018949713 | ISBN 9781498565653 (cloth: alk. paper) | ISBN 9781498565660 (electronic)

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

Printed in the United States of America

O God of Love, O King of Peace,

make wars throughout the world to cease.

President Ronald Reagan,

quoting from the hymn by Henry Baker

in his Address to the Nation on Strategic

Arms Reduction and Nuclear Deterrence

The White House, November 22, 1982

Chapter 5

Cold Storage

The Delinking of the Nuclear and Space Talks

The post-Reykjavik blowback had shaken Washington to an extent. The NATO Allies had been shocked by US generosity. The United States had proposed the elimination of all strategic nuclear weapons. The Europeans feared the emergence of a condominium in international relations. The European Allies now focused on the development of SDI as a Western concept to undermine the US negotiation position. NATO Europe backed the US Congress to fund SDI bottom-up approaches that strengthened deterrence. The Europeans pushed early BMD deployments to torpedo superpower cocreation. The Western concept of early SDI deployments conflicted with the US pledge to eliminate ballistic missiles prior to the cocreation of a ballistic missile defense. This procedure was needed to forestall the emergence of first-strike capabilities for a deploying party. The Western European Allies despised the phased Gorbachev Plan. The Europeans fiercely opposed the planned phase II multilateralization of strategic arms control. The NATO responses altered US defense planning. The JCS shied away from a total elimination of nuclear weapons. Americas future security depended on SDI, air-breathing systems, and smart high-tech and stealth technology weaponry. The White House furthermore decided to push (1) early deployments of space-based boost-phase interceptor systems and (2) a sharing concept to preserve the Reagan vision. The latter was endangered by Congressional funding for the Atlanticist bottom-up approach. The Soviet Union was unpleasantly surprised by the repositioning of Washington. Moscow did not trust US motives. The very fact that the United States pushed SDI early boost-phase deployments and simultaneously limited reductions to a central basket of ballistic missiles made the Kremlin fear a high-tech domination scheme. Moscow, however, was aware of the hostile reactions of the European Allies to the Reykjavik bomb. NATO Europe was a stumbling block. A European Reykjavik might be needed to move the Old Continent to accept a beneficial superpower cocreation. The next chapter of this monograph is dealing with the geopolitics of the revolution in military affairs. The US de facto adopted the Gorbachev Plan. SDI was placed in cold storage. SDI R&D continued. The guiding vision of a weaponization of space was preserved. The Soviet Union and the United States agreed to transform defenses and modernize bipolarity. The vision of a collective security system that firmly established mutually assured security guided the superpower planning.

The Washington and Moscow Summits

Superpower dtente had to be preserved. The parties urgently needed to present a breakthrough on the path to global zero to their national constituencies. Lieutenant General Edward Rowny urged the US president to finalize the test case: the INF Treaty and to preplan a post INF nuclear posture. The forthcoming INF agreement had to have a radiating influence, that is, a positive impact on global disarmament. The geopolitical consequences had to be planned prior to the signing of the INF accord. The INF Treaty had the potential to decouple European and US security. The global zero for INF systems was breaking the escalation ladder to strategic exchanges. The option of limited wars emerged yet again on the horizon. The United States had to cater to European theater interests and therefore develop a comprehensive security concept. The Soviet strategy of divide and denuclearize needed attention, too. The Soviet vision of a denuclearized Central Europe between the superpowers was dangerous for Western unity. The idea of a third zerothe elimination of all ballistic, Euro-strategic, and tactical nuclear weaponswas problematic. Battlefield nuclear weapons had originally been introduced to the NATO theater in order to balance the Soviet conventional superiority. NATO had to urgently debate the modernization of SRTNF and the option of a limited-point defense to protect these new assets. The potential of the follow-on system to lance (FOSTL) and the flexible lightweight agile guided experiment (FLAGE) interception system deserved to be studied. European security was to be assured without risking an escalation threat beyond the theater. It had to pursue the Gorbachev Plan pure and simple. SDI was to remain a pure research project for the foreseeable future.

The advice by Rowny and Nixon was right on the mark. The Soviet Union was keen to charge ahead. Gorbachev, however, was shocked by NATO European behavior. Gorbachev was not too inclined to play a European card. The Kremlin preferred to force Europe to fall in line. The Kremlin even questioned the merit of the INF Treaty. The superpowers had to take precautions. Moscow and Washington had to force the European NWS to commit to a reduction of their potentials prior to the bilateral disarmament of INF systems. The Warsaw Pact, Chiefs of Staff Committee Meeting in Moscow of May 1825, 1987, offered the Soviet representative, Marshal Sokolov, an opportunity to alert his colleagues that France and Great Britain [were] not prepared at the present time to partake in the reduction of nuclear weapons. The arms control agenda stalled due to the irresponsible behavior of the European NWS. The deterrent forces of the European NWS altered the bloc balance. The SU cannot agree to a zero solution in Europe, since this would give NATO a unilateral advantage.

The wider INF Treaty settlement made it indispensable for the United States to reevaluate the wider Soviet strategy. The geopolitical core aims of the Kremlin needed scrutiny. The Kremlin first and foremost needed breathing space for the Soviet economic and political reform agenda. Glasnost, perestroika, and arms reductions were pushed by the Kremlin to improve the competitiveness of the Soviet Union. Moscow had three core strategic aims: (1) the enhancement of the Soviet power potential, (2) a revival of the UN system, and (3) the denuclearization of Central Europe. The UN Security Council had to be turned into a real directorate for global affairs. The unified European continent was to serve as a buffer between the superpowers. The existing bloc organizations were earmarked for a modernization and transformation to foster the establishment of a strategic partnership between the blocs.

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.