chapter one

From Dusk to Dawn

Origins and Effects of the Reagan Revolution

In the very late twentieth century, capitalism seemed triumphant throughout the worldthat is why everyone was debating the meaning of globalization (on which see chapter 6 below). But in the 1970s, capitalism did not look like the wave of the future. Then, as now, it seemed to be on its last legs. Remember, the Soviet Unionthe evil empire, as Ronald Reagan would call itwas still intact and was about to invade its neighbor Afghanistan (yes, the very same Afghanistan the United States invaded in 2001). Communist Chinas drive to industrialize was in full stride. And socialist movements in Latin America were flourishing; the Nicaraguan Sandinistas, who came to power in 1979, were merely the most visible and effective of these movements.

At the cutting edge of capitalism, however, back in the United States, the economy was a mess and the future of private enterprise was in doubt. The oil shock of 1973 to 1975, which tripled the price of imported crude oiland thus the price of gasolinestill crippled automobile manufacturing, the signature American industry; indeed, the Chrysler Corporation had filed for bankruptcy and begged the U.S. Congress to come to its rescue with outright grants and guaranteed loans. The housing market and consumer spending were severely cramped by double-digit interest rates and unprecedented inflation (to the tune of 20 percent per year). Moreover, occupational safety and environmental protection, the new watchwords of government regulation and public opinion, had apparently trumped the requirements of

economic growth. Back then even the Federal Reserve was clueless. And everybody knew it.

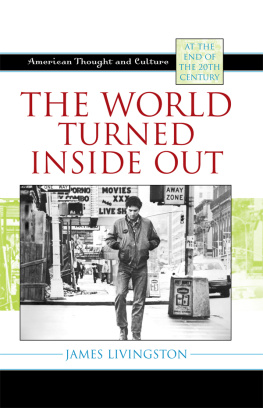

Meanwhile, New York City, the financial headquarters of the capitalist world (then still known in Cold War parlance as the free world) was close to bankruptcy. Huge swaths of Brooklyn and the South Bronx were smoldering ruins. Garbage rotted in the streets of Manhattan. The subways were visibly decaying, most dangerously after darknot because graffiti artists were sculpting a new underground alphabet, but because the physical plant was expiring and the middle-class commuters were fleeing. And the intersection of Broadway and Forty-second StreetTimes Square, where the ball drops on New Years Evewas not a tourist destination unless your purpose in coming was pornographic. It was a sexual bazaar, an open-air brothel even in winter, where hustlers, performers, and pimps often outnumbered pedestrians.

Many interested observersfrom filmmakers like Martin Scorsese to social scientists like James Q. Wilsonsaw these mean streets as thoroughfares to the future of the nation; for they seemed to have channeled the social, political, and cultural extremes inherited from the 1960s and then closed the off-ramps. The plight of New York City was, in this sense, a symptom of systemic failure, of disease in the larger body politic. It was a miniature version of a general crisis in capitalism. And everybody said it.

At any rate the cultural and intellectual history of the late twentieth century was framed by the perception of this bifocal crisis. For example, the ambivalent yet rigorous defense of capitalism which goes by the name of neoconservatism was a direct result of both the general crisis in capitalism and the specific spectacle of New York City. So too was deregulation, the movement to lighten the visible hand of the state which was originally sponsored by liberals like Ted Kennedy and Jimmy Carter. And so was the Reagan Revolution, the touchstone of contemporary conservatism.

The Supply Side

Let us look more closely, then, at the fears and the hopesand the ideasthis crisis created. Whether liberal or conservative, those who examined the economic problem typically interpreted it as a political issue animated by deeper cultural change that started in the 1960s. Whether liberal or conservative, their short-run solution was ideological exhortation and their long-run solution was victory in a protracted war of cultures that would necessarily engage the hearts and minds of every American. To solve the economic problem was to convince the American people that unleashing market forces would reinvigorate freedom, progress, and moralityor that state-centered planning for growth would underwrite liberty, equality, and democracy. As we shall see, it was a hard sell either way.

The economic experience of the Great Depression and the Second World War had established a Keynesian consensus in Washington which guided both Democratic and Republican administrations during the Cold War (ca. 19471989). In fact, the Republican presidents before Reagan were big

government liberalsRichard Nixon imposed mandatory wage and price controls to subdue inflation, and Gerald Ford followed suit. The Keynesian consensus, from Left to Right, was based on two assumptions. First, government policies, especially decisions on spending (the federal budget) and interest rates (the Federal Reserve), were the keys to economic growth. Second, the scale of consumer spending was more important than the scope of private investment in determining the rate of economic growth.

This consensus expired in the late 1970s as a result of an economic reality

the new combination of price inflation and lower productivity that went by the name of stagflationand an intellectual movement that came of age at the same moment. The maturing movement was crucial because it explained the new reality and offered an alternative. In its absence, a larger dose of Keynesian policies would have seemed natural and necessary. This intellectual movement was the supply-side revolution that gave Ronald Reagan the broadband credentials he needed to win the presidential primaries and then the presidency itself. In the name of renewed growth, its proponentsJack Kemp, Jude Wanniski, Paul Craig Roberts, Arthur Laffer, David Stockman, Irving Kristolwanted to repeal the welfare state and liberate the private sector from every impediment, including taxes. As Stockman, a Michigan congressman who would eventually run Reagans Office of Management and Budget, put it, the supply-side program required the radical dismantling of state-erected barriers to economic activity.

It also required tax cuts because increased investment would not happen unless entrepreneurs could keep most of the wealth they generated. This was a matter of incentives, according to the supply-siders, who drew on a large body of research (much of it done by Martin Feldstein of the National Bureau of Economic Research) showing that higher tax rates on personal and corporate income caused lower investment. The loss of tax revenue after the cuts they proposed would be more than offset, they argued, by the gain in tax revenue generated by the faster growth determined by greater investment, which would, in turn, be elicited by the incentive of higher retained earnings. Their argument never made any empirical sensethe numbers just dont add up, as George H. W. Bush pointed out in 1980, when he ran against Reagan in the primariesbut the arithmetic was beside the point. The

supply-siders were arguing that individual saving and private investment, not consumer spending and government policies, were the keys to economic growth. They were arguing against history.

For the history of the twentieth century is the record of economic growth accompanied, perhaps even caused, by declining saving and investment, on the one hand, and rising consumption, on the other. It is also the record of massive market failure: No one except the most devoted disciples of Milton Friedman can still believe that the Great Depression was the result of the Federal Reserves mistakes (see the appendix on the 20082009 economic crisis). Once you acknowledge these simple facts, the supply-side argument sounds more or less absurd. But it was never offered as merely a recipe for economic growthit was the blueprint for a moral renewal through which the American people would relearn the virtues of hard money, balanced budgets, and real work. Wealth creation would replace redistribution, as Stockman and many others put it. By this they meant two things. First, the limits to growth animated by markets were artificial bureaucratic conventions, not natural environmental constraints. Faster growth through deregulation would underwrite social justice by generating the jobs necessary to get the poor off the welfare rolls.