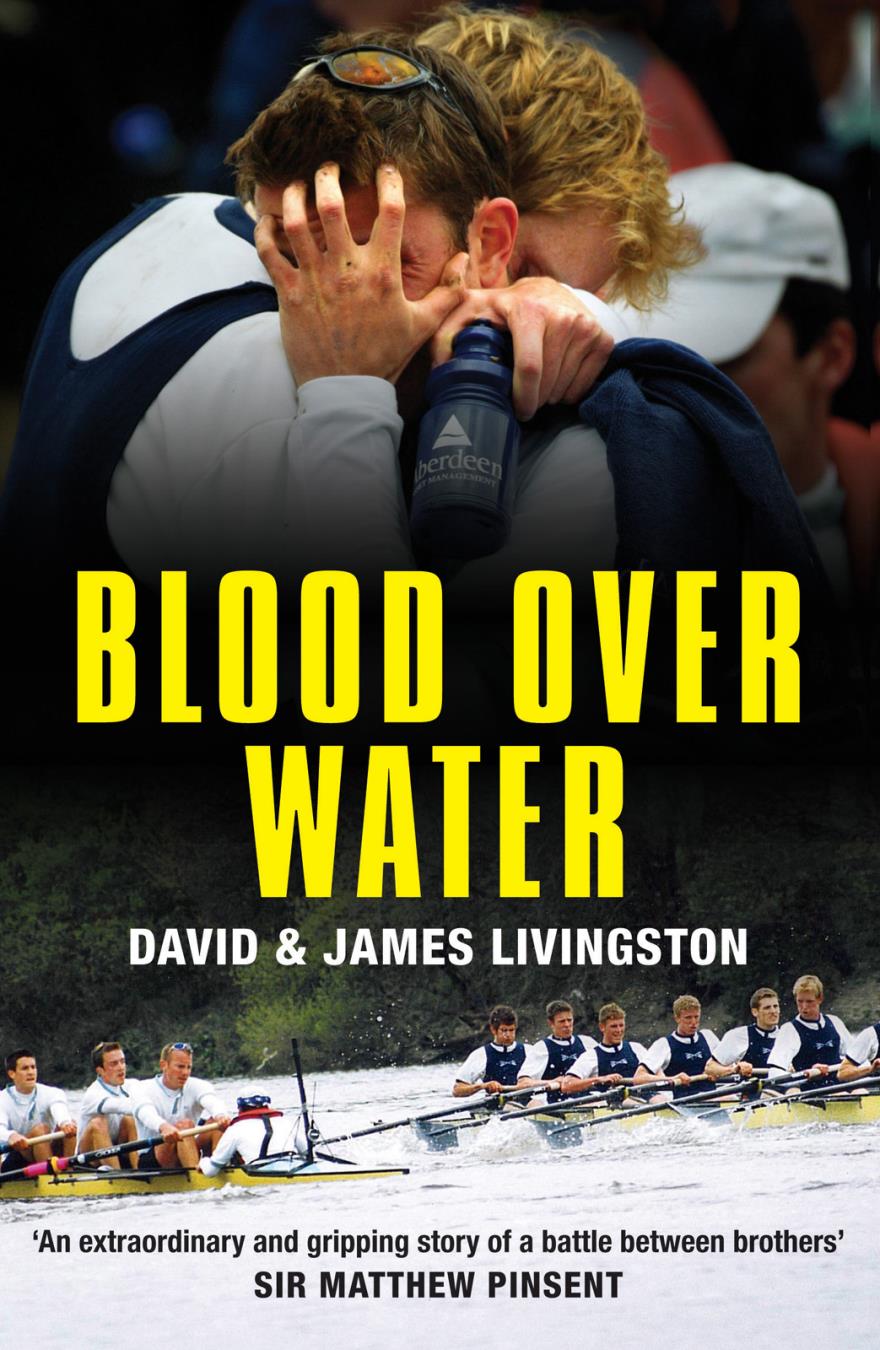

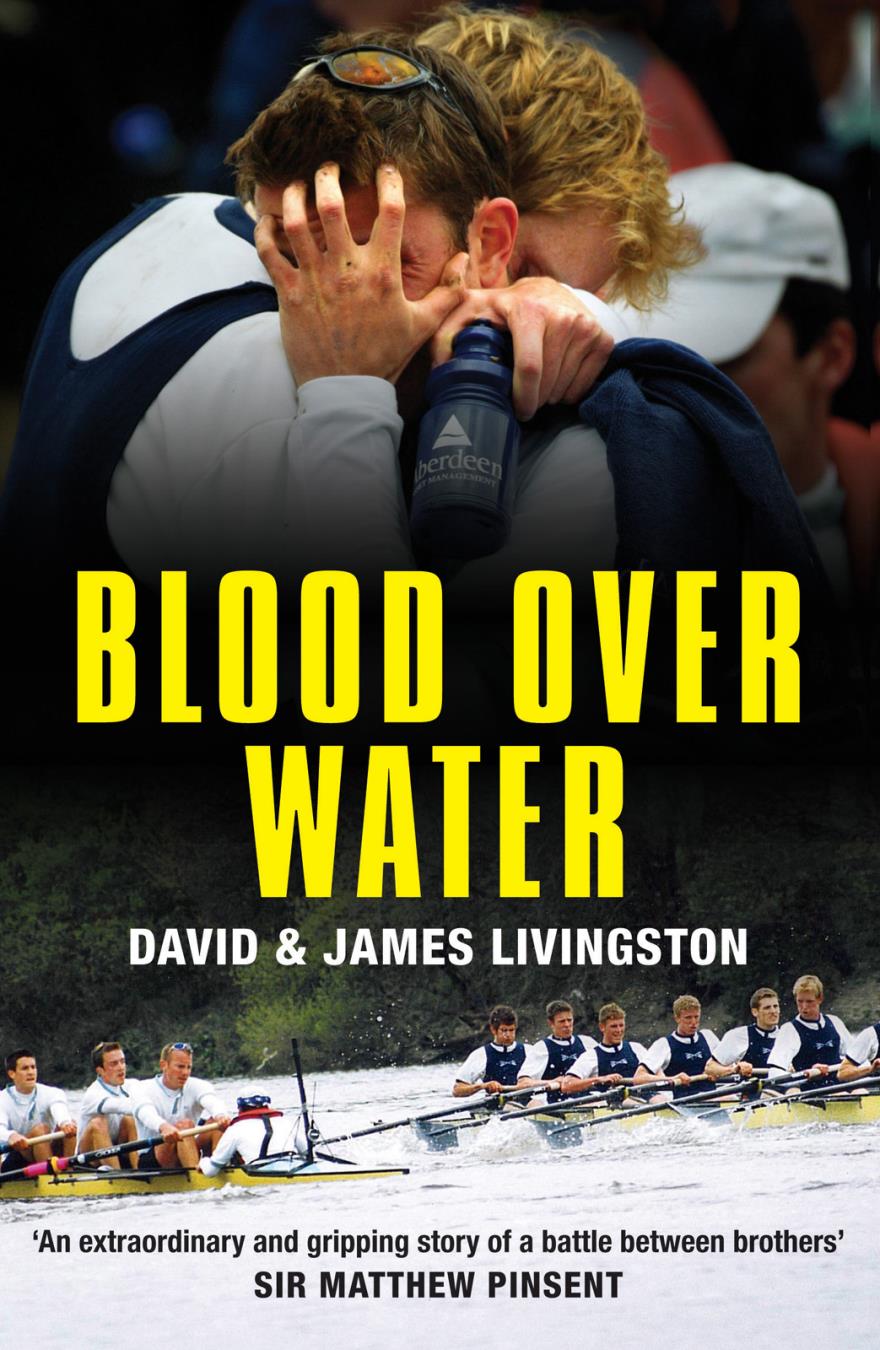

BLOOD OVER WATER

David and James Livingston

BLOOMSBURY

LONDON BERLIN NEW YORK

For Mum and Dad

Contents

It is an annual four-and-a-quarter-mile rowing race from Putney to Mortlake on the river Thames between two of the most prestigious universities in the world, Oxford and Cambridge. The competitors train twice a day, six days a week, striving to achieve their goal of representing their universities. Everything else in their lives becomes secondary. It is not done for money but for honour and the hope of victory. There is no second place, as second is last. They call it simply The Boat Race.

1999

James:

Come on, Dave, well miss it!

Cycling through Richmond Park, my rangy, blond fifteen-year-old brother, riding a hand-me-down bike that is patently too small for his long legs, puts on a spurt of effort to catch up with me and our friends Matt and Ben.

Two sets of brothers, we whizz out of the park, down Roehampton Lane and across the green into Putney, regularly checking our watches. Its a glorious sunny day in the school holidays and were excited. Squeezing on to the embankment through packed crowds, about half a mile up from Putney Bridge, we peer expectantly downriver. Our heroes are lining up. A helicopter passes overhead, following our line of sight.

What time do you make it, Smithy? I ask.

Matt checks his watch again. They should be starting any minute now.

On cue a roar goes up, rising like high-pitched thunder. Weve got to get to the front. We push through the crowd until the front wheels of our bikes are almost hanging over the river, craning our necks to see upstream.

Here they come! shouts Matt, as two boats edge into view around the curve in the river. They close rapidly on our position, borne by the tide and the efforts of the oarsmen. Our part of the bank erupts.

Come on, Cambridge! I shout.

Go, Oxford! screams Matt.

Cambridge! shouts Dave.

The crews draw level with us. We pull our bikes away from the rivers edge and start to cycle manically along the bank, weaving through the packed crowd.

Coming through!

Watch out!

Cycling at breakneck pace, we almost keep up with the crews, our eyes snapping back and forth from the people on the bank ahead of us to the combatants. Oxford are beginning to struggle and their fear and growing desperation are evident, even to us on bikes a hundred feet away. Cambridge look invincible and their strokeman, who we know is a massive German called Tim Wooge, appears magically unconcerned by the competition.

Cambridge! we Livingstons yell happily.

Oxford! Matt shouts stubbornly, even though, despite their best efforts, the crew is continuing to fall behind. Ben is happy just to watch. We are all in awe of those on the water, so perfectly synchronised, keeping up such an impossible tempo.

At Hammersmith Bridge, when the thickness of the crowd becomes impossible, we pull our bikes to a halt and watch until the boats move out of sight, Cambridge comfortably in the lead.

We turn to each other, laugh at the madness of a race so long, and begin the ride home.

It is not the critic who counts The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena, whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood If he fails, at least he fails while daring greatly; so that his place shall never be with those cold and timid souls who know neither victory nor defeat.

Theodore Roosevelt, Citizenship in a Republic

Paris, 23 April 1910

2002

James:

Saturday 30 March 16:03, Putney Bridge

The murky water of the Thames swirls quickly under the boat, the rising tide curling into eddies and ripples around our hull and oars. Closing my eyes, I can feel my heart thumping against my ribcage, almost keeping time with the thunk, thunk, thunk, thunk of the blades of the helicopter hovering above us. The chopper seems dark and oppressive, a malevolent presence; its down draught pressing upon us, its cameras locked on.

God, dont fuck this up.

Get straight, both crews. The umpires loudhailer breaks my trance.

Ellies voice comes through the boats speaker system, strong, clear and full of nervous energy.

Hold it, Sam!

Sam, the American rowing international sitting behind me, squares his oar face into the water and the resistance against the tide slews the boat violently round to the right.

Too much, Sam. Tom, take us back, Ellie demands, her voice ratcheting upwards a notch, straining to compete with that of the umpire, who is issuing increasingly fraught instructions in the effort to get the two boats aligned. Were already several minutes past race time. The TV slot is ticking away, the sponsors restless.

In the bow seat, Tom, our president, squares up his oar and we swing back to my left. The tide keeps hurrying past us, rushing to fulfil its promise as the highest tide of spring.

I look up at Sebs square back and reach out and grasp his shoulder. Lets go for it, mate. With you all the way.

He turns, grasps my forearm in a grip which betrays his iron strength and nods to me, slowly, almost reverently, before turning back.

Hes already competed in two Olympic Games with the German team and is renowned for his machine-like nature in competition. What am I doing here? I havent been to one Olympics, let alone two!

Dont mess this up.

Im mortally afraid of losing and even worse, being singled out as the reason for the defeat. My overactive brain trips to a text message of support I received a few days ago from a good friend at college: What is our aim? Victory at all costs, victory in spite of terror. Victory, however long and hard the road may be, for without victory there is no survival. You the man.

Eyes open again, looking above Sebs head; another few feet away is the shaggy hair of Josh, the tallest man ever to row in the Boat Race, another World Championship medallist, for Great Britain this time. Six foot ten.

What am I doing here?

Sixty feet further on is Putney Bridge, packed deep with people waving flags, holding light and dark blue balloons and shouting.

In the Surrey stakeboat, let them out about a foot, comes the tense voice from the loudhailer again. The umpire must have been told that the boats are not quite level. I curse under my breath as the Oxford hull slips up past us a little. Every inch is going to be an agonising battle and I develop an instant and irrational hatred of the umpire. Hes meant to be a Cambridge man too. Traitor.

I glance to my oar, out to the left of the boat. Looks fine. Beyond the boats, on the Fulham bank, stands the University Stone, the official start line for the race since it moved from Westminster to what was then the quiet country town of Putney in 1845, sixteen years after the inaugural race at Henley. Around the stone are more people, against the backdrop of a vast TV wall, twenty-five feet high. Its showing live BBC coverage of the race. The cameraman is panning along our Cambridge line-up.

Jesus, there I am.

I snap my eyes away, over to the right, and there are Oxford. In their stern, at stroke next to their cox, sits Matt. I could pick his back out a mile off, having had a similar view for years in the school eight. He was one of my best friends. Wed gone through bad haircuts together; discovered girls together, sometimes the same ones (although not at the same time); started rowing together; won and lost together; and grown from boys to young men alongside one another. Wed even played in a rock band together. We were awful. Matt was perhaps the worst bass player ever to hold the instrument and I was no better on the guitar, not that it mattered.

Next page