CHAPTER ONE

Having rowed myself since the tender age of twelve and having been around rowing ever since, I believe I can speak authoritatively on what we may call the unseen values of rowingthe social, moral, and spiritual values of this oldest of chronicled sports in the world. No didactic teaching will place these values in a young mans soul. He has to get them by his own observation and lessons.

George Yeoman Pocock

M onday, October 9, 1933, began as a gray day in Seattle. A gray day in a gray time.

Along the waterfront, seaplanes from the Gorst Air Transport company rose slowly from the surface of Puget Sound and droned westward, flying low under the cloud cover, beginning their short hops over to the naval shipyard at Bremerton. Ferries crawled away from Colman Dock on water as flat and dull as old pewter. Downtown, the Smith Tower pointed, like an upraised finger, toward somber skies. On the streets below the tower, men in fraying suit coats, worn-out shoes, and battered felt fedoras wheeled wooden carts toward the street corners where they would spend the day selling apples and oranges and packages of gum for a few pennies apiece. Around the corner, on the steep incline of Yesler Way, Seattles old, original Skid Road, more men stood in long lines, heads bent, regarding the wet sidewalks and talking softly among themselves as they waited for the soup kitchens to open. Trucks from the Seattle Post-Intelligencer rattled along cobblestone streets, dropping off bundles of newspapers. Newsboys in woolen caps lugged the bundles to busy intersections, to trolley stops, and to hotel entrances, where they held the papers aloft, hawking them for two cents a copy, shouting out the days headline: 15,000,000 to Get U.S. Relief.

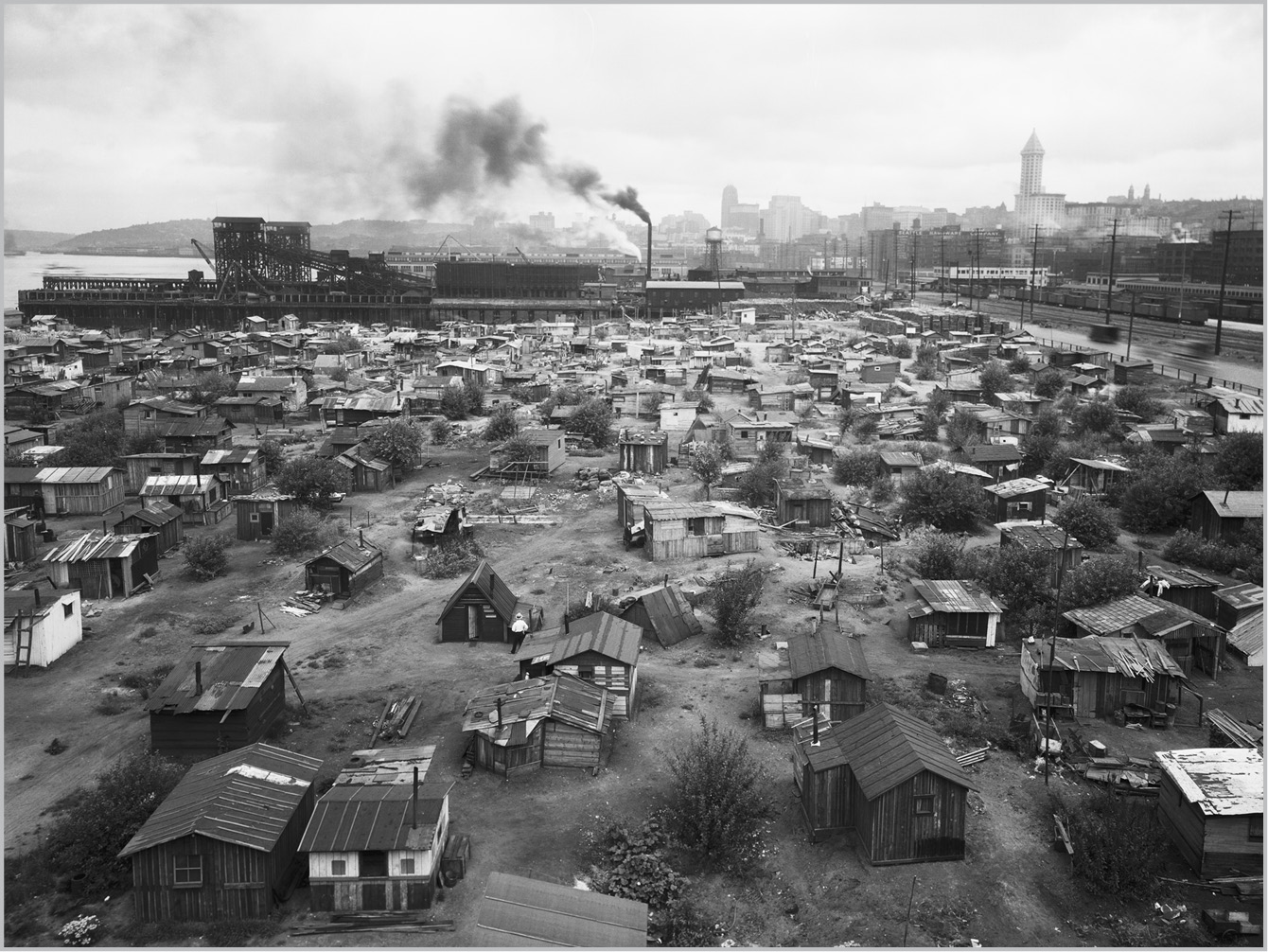

A few blocks south of Yesler, in a shantytown sprawling along the edge of Elliott Bay, children awoke in damp cardboard boxes that served as beds. Their parents crawled out of tin-and-tar-paper shacks and into the stench of sewage and rotting seaweed from the mudflats to the west. They broke apart wooden crates and stooped over smoky campfires, feeding the flames. They looked up at the uniform gray skies and, seeing in them tokens of much colder weather ahead, wondered how they would make it through another winter.

Northwest of downtown, in the old Scandinavian neighborhood of Ballard, tugboats belching plumes of black smoke nosed long rafts of logs into the locks that would raise them to the level of Lake Washington. But the gritty shipyards and boat works clustered around the locks were largely quiet, nearly abandoned in fact. In Salmon Bay, just to the east, dozens of fishing boats, unused for months, sat bobbing at moorage, the paint peeling from their weathered hulls. On Phinney Ridge, looming above Ballard, wood smoke curled up from the stovepipes and chimneys of hundreds of modest homes and dissolved into the mist overhead.

It was the fourth year of the Great Depression. One in four working Americansten million peoplehad no job and no prospects of finding one, and only a quarter of them were receiving any kind of relief. Industrial production had fallen by half in those four years. At least one million, and perhaps as many as two million, were homeless, living on the streets or in shantytowns like Seattles Hooverville. In many American towns, it was impossible to find a bank whose doors werent permanently shuttered; behind those doors the savings of countless American families had disappeared forever. Nobody could say when, or if, the hard times would ever end.

And perhaps that was the worst of it. Whether you were a banker or a baker, a homemaker or homeless, it was with you night and daya terrible, unrelenting uncertainty about the future, a feeling that the ground could drop out from under you for good at any moment. In March an oddly appropriate movie had come out and quickly become a smash hit: King Kong. Long lines formed in front of movie theaters around the country, people of all ages shelling out precious quarters and dimes to see the story of a huge, irrational beast that had invaded the civilized world, taken its inhabitants into its clutches, and left them dangling over the abyss.

There were glimmers of better times to come, but they were just glimmers. The stock market had rebounded earlier in the year, the Dow Jones Industrial Average climbing an all-time record of 15.34 percent in one day on March 15 to close at 62.10. But Americans had seen so much capital destroyed between 1929 and the end of 1932 that almost everyone believed, correctly as it would turn out, that it might take the better part of a generationtwenty-five yearsbefore the Dow once again saw its previous high of 381 points. And, at any rate, the price of a share of General Electric didnt mean a thing to the vast majority of Americans, who owned no stock at all. What mattered to them was that the strongboxes and mason jars under their beds, in which they now kept what remained of their life savings, were often perilously close to empty.

A new president was in the White House, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, a distant cousin of that most upbeat and energetic of presidents, Teddy Roosevelt. FDR had come into office brimming with optimism and trumpeting a raft of slogans and programs. But Herbert Hoover had come in spouting equal optimism, buoyantly predicting that a day would soon come when poverty would be washed out of American life forever. Ours is a land rich in resources; stimulating in its glorious beauty; filled with millions of happy homes; blessed with comfort and opportunity, Hoover had said at his inaugural, before adding words that would soon prove particularly ironic: In no nation are the fruits of accomplishment more secure.

At any rate, it was hard to know what to make of the new President Roosevelt. As he began putting programs into place over the summer, a rising chorus of hostile voices had begun to call him a radical, a socialist, even a Bolshevik. It was unnerving to hear: as bad as things were, few Americans wanted to go down the Russian path.

There was a new man in Germany too, brought into power in January by the National Socialist German Workers Party, a group with a reputation for thuggish behavior. It was even harder to know what that meant. But Adolf Hitler was hell-bent on rearming his country despite the Treaty of Versailles. And while most Americans were distinctly uninterested in European affairs, the British were increasingly worked up about it all, and one had to wonder whether the horrors of the Great War were about to be replayed. It seemed unlikely, but the possibility hung there, a persistent and troubling cloud.

The day before, October 8, 1933, the American Weekly, a Sunday supplement in the SeattlePost-Intelligencer and dozens of other American newspapers, had run a single-frame, half-page cartoon, one in a series titled City Shadows. Dark, drawn in charcoal, chiaroscuro in style, it depicted a man in a derby sitting dejectedly on a sidewalk by his candy stand with his wife, behind him, dressed in rags and his son, beside him, holding some newspapers. The caption read Ah dont give up, Pop. Maybe ya didnt make a sale all week, but it aint as if I didnt have my paper route. But it was the expression on the mans face that was most arresting. Haunted, haggard, somewhere beyond hopeless, it suggested starkly that he no longer believed in himself. For many of the millions of Americans who read the