HONOURABLE CHARLES ZARAKA : A most illuminating spectacle, Mr Chan. The nations of the world about to struggle for supremacy on the field of sports. Yet behind all this there is another struggle going on constantlyfor world supremacy in a more sinister field. It is not a game for amateurs, Mr Chan. I hope you get my meaning.

CHARLIE CHAN : Could not be more clear if magnified by 200-inch telescope.

T HE SMALL TOWN of Dallgow-Doeberitz lies some 20 miles west of Berlin. It is a down-at-heel place, and its unmanned and heavily graffitied railway station greets the visitor with an air of tired menace. A few all-day drinkers sitting in a scratchy beer garden add a sense of decay, and it quickly becomes clear that the name of Dallgow-Doeberitz will never trouble the pages of any guidebook. Unsurprisingly, there is no taxi rank at the station, and the only way to summon a taxi is to ask one of the drinkers whether he knows of a firm. In return for a Pilsener, a telephone number will be issued, and after an uneasy wait, a creaky Mercedes might well turn up. The drivers surprise at seeing that he has a tourist for a fare will be magnified when he is told of his destination: die Olympische dorf .

After a five-minute drive along a main road, the driver turns right on to a track that runs over some rolling scrubland. The noise of crickets fills the air, which is still warmed by a setting September sun. The cabbie then turns right again, and heads towards a stand of unkempt fir and silver birch. The occasional dilapidated rooftop can be seen through gaps in the trees. After confirming that this is really where his fare wants to go, the driver heads down the ever worsening track into what remains of a village that housed over four thousand of the worlds finest athletes in the summer of 1936.

Seven decades and the Soviet army have taken their toll on what should be a preserved national monument. The 150 single-storey stone huts are being consumed by undergrowth, and those windows that are not boarded up are smashed. The large crescent-shaped Housing Building, which boasted forty kitchens, each of which specialised in a different national cuisine, resembles a derelict block of flats on the most deprived of estates. On the practice running track, its cinders tufted with weeds, a flock of sheep grazes. A row of foot-high concrete blocks gives the suggestion of a viewing platform, from where athletes could monitor their rivals abilities and techniques.

The dereliction and the eeriness of the village make it hard to envisage it as a centre of bustling joy. Could this really be what one American athlete described as a sight to behold, with its wild animals running over the groundsand green grass mowed like a golf course? It is more reminiscent of a concentration camp, the buildings giving the impression that something bad happened here. Like so many other decaying structures from the Nazi period, there is the normal sense of Ozymandias, the ruins symbolic of collapsed majesty. It is not a place to be after dusk, and with the taxis meter running, it is soon time to leave.

Unlike the village, the other relic from the Eleventh Olympiad of the Modern Era is a far more impressive and intact affair. Situated halfway between Dallgow-Doeberitz and the centre of Berlin, the mighty Olympiastadion is as awe-inspiring as Adolf Hitler intended it. Clad in pale Franconian limestone, the stadium almost glows in the sunlight, its magnificent pillared curves elegant and powerful.

It is only upon entering the building that its sheer scale can be appreciated. As the stadium sinks 40 feet below ground level, the outside of the building gives the lie to its capacity. In 1936, it accommodated some 100,000 spectators, although today, because of the use of seats, that number has shrunk to 76,000. Nevertheless, it is vast, and unlike so many of todays steel-and-glass structures, the limestone gives the building a more natural air.

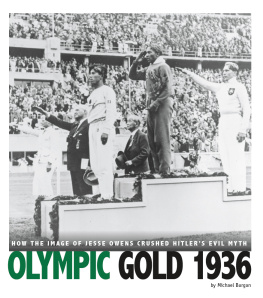

In contrast to the Olympic village, it is easy to imagine the dramatic events that took place here seventy years ago. The VIP platform where Hitler and his acolytes watched the infuriatingly fast progress of Jesse Owens eighty feet below still stands. The brazier that contained the Olympic flame is here too, along with the names of the gold medal winners carved in stone near by. Through the gap in the stadiums west end can be seen the 247-foot bell tower on the other side of the immense May Field. The tower once contained a bell that weighed over 30,000 pounds, its toll summoning the youth of the world to the Games. Its chimes would have filled the stadium, but not as effectively as the sound of 100,000 singing Deutschland ber Alles whenever a German took gold.

Whereas other Nazi edifices such as the rally grounds at Nuremberg are rightly abandoned, this is a building still very much in useeven playing host to the 2006 World Cup final. Although some argue that a structure so closely associated with the Nazi period should not be used, it would seem churlish (and uneconomical) to abandon so handsome and vast a building. In 1936 it may well have been regarded as an architectural embodiment of the waxing power of the new German Reich, but in 2006, the seventieth anniversary of the Nazis Olympics, it stands as a symbol that Germany has the ability to come to terms with its past. Why should it not be used? What harm does it do? The shape of the Olympic Stadium does not register as a symbol of evil in the same way as the infamous entrance to Auschwitz, with its railway lines converging to pass under its all-seeing watchtower. The stadium may well not be free from guilt, but like many associated with the Nazi regime, it does not necessarily deserve the death penalty.

What follows is the story of what happened inside that village and stadium. But the story is set elsewhere too, from the plains of the American Midwest to the hilltop villages of the Korean peninsula. And if its locations are global, then its themes are of a similar stature, because this is not just a story about sport. It is also about politics, about the titanic fight between fascism and democracy. It is about racism and those who struggled to overcome it. It is about the glory of winning medals, and the despair that sees men putting bullets through their own heads. It is about Olympism itself, and how the Games of 1936 saw an ideal marriage between it and Nazism. Above all, the story shows how it is impossible to keep sport out of politics, for the simple reason that there are those who will always use athletes as their unwitting tools. Those two weeks in Berlin show how easily the naive worthiness of the Olympics could be corrupted to suit the ambitions of repellent men. It is a lesson that still needs to be learned.

Guy Walters

Heytesbury

February 2006