Berlin was very, very long ago, and we were all so young... Ill try to remember how it was, was Basil Dickinsons response when I first asked to interview him about his experiences as an Olympian in 1936.

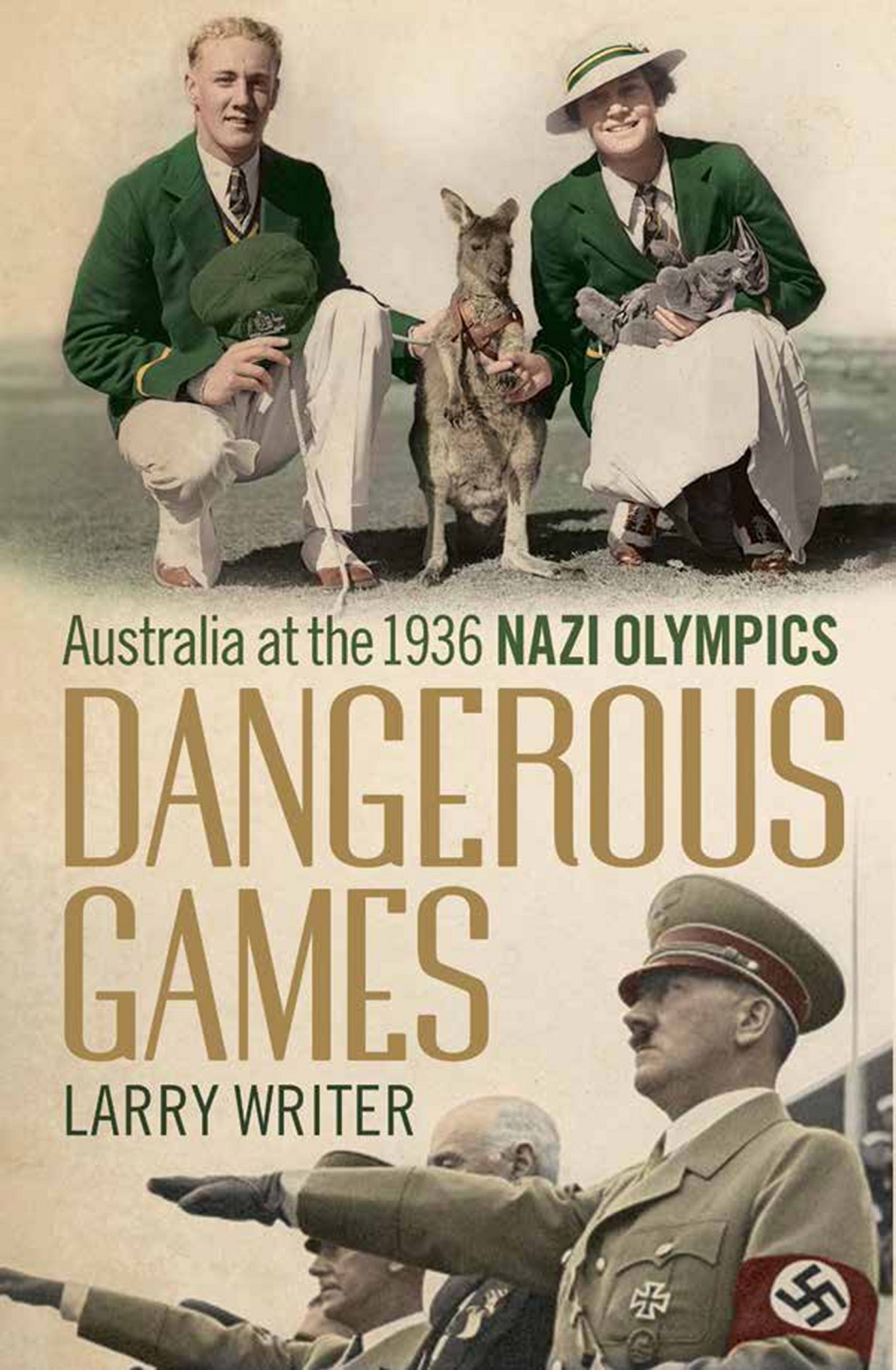

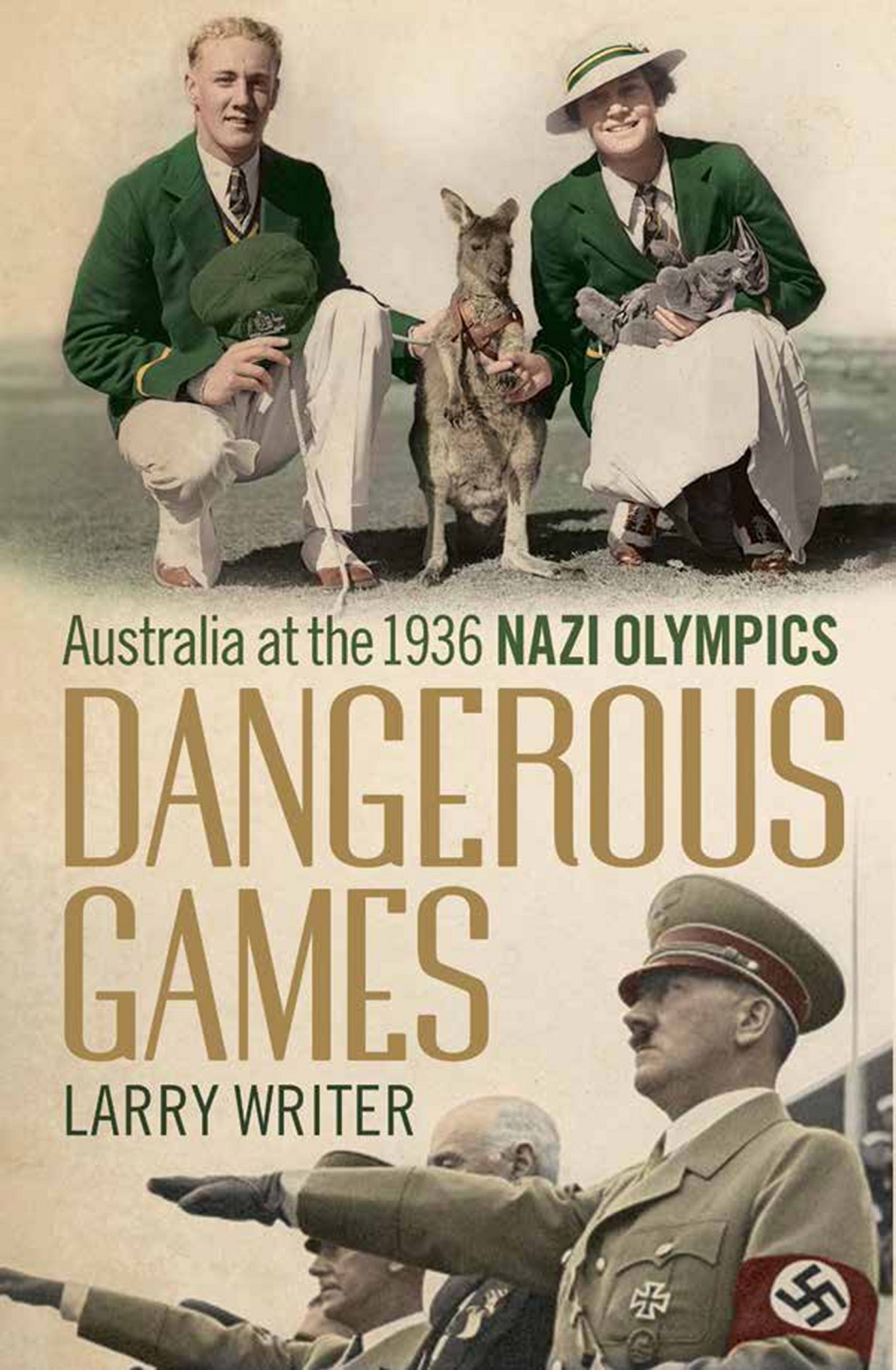

Late in 2012having written on sport for 30 years and after viewing Leni Riefenstahls Olympia and reading Guy Walters Berlin Games, Christopher Hiltons Hitlers Olympics and David Clay Larges Nazi GamesI came to believe that there was room among this excellent literature on the XIth Olympiad for a book about the seldom recounted experiences of the Australian team who competed. Who was in the team? How did they fare? What did they think of Hitler and his Nazis, and of Jesse Owens? Of each other? What was it like to be in old Berlin before it was destroyed by war? Were the athletes different from, or similar to, modern-day Australian champions? To answer my questions and perhaps, if the information was available, write the story of Australia at the Berlin Olympics, I knew I could search for official documents, diaries and mementoes kept privately or donated to libraries. The reports of sports experts, journalists and eyewitnesses written and broadcast before, during and after the Olympics were all available in libraries or newspaper archives. I could travel to Berlin and be guided by experts through what remained of Berlin circa 1936 and the Reich Sports Field, and steep myself in local records of the time. Yes, but what would make my book really worthwhile would be to find a primary source, to interview at length an athlete from that 1936 squad. Any such person would have to be well into their nineties. Perhaps, I worried, there was nobody left alive.

After some sleuthing, I learned that there was: Basil Dickinson. His daughter, Pauline Watson, told me that Basil was 98 and in an aged care facility, but his mind and memory were sharp.

Basil and I met for the first time in his room at the nursing home in Kingswood, west of Sydney, in June 2013. He was sitting on the edge of his bed, a trim man with a shock of wiry white hair atop an intelligent face. His manner, though friendly, was formal and courtly, befitting a man of his vintage. He was impeccably dressed in slacks and sports shirt and his shoes were polished. His room was neat. Bright winter morning sunlight flooded through his window onto his perfectly made bed, his furniture and shelves, which held books on sport and poetry (Oodjeroo Noonuccal, Henry Lawson, Banjo Paterson, the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, the very book he purchased in Aden when Mongolia dropped anchor there in 1936 bound for Europe). By his bed were recent and past photographs of Basil and his family, and stacked on a tape player, cassettes of classical music, Leonard Teale reading the works of Paterson, Lawson and other bush poets, and Geoffrey Gurrumul Yunupingus Gurrumul. By his bathroom door was his walking frame, an ironic aid for one who was once a world-class athlete. On a bedside table was that mornings broadsheet newspaper, which Basil, a voracious reader of political news and arts features as well as the sports pages, had already read from cover to cover. Well, what can I tell you? he said before we began our first interview. I want this to be accurate, exactly the way it was.

I recorded Basils recollections and insights about the 1936 Olympics and his life during a dozen or more meetings at the nursing home. When I arrived he would have his Olympic books, pamphlets and photographs arrayed on his bed and bedside chair as ready references. Speaking softly and thoughtfully, Basil brought vividly to life long-ago events and memories, some of which he had forgotten, perhaps repressed, until encouraged to delve into his past to reclaim them.

I like to think he looked forward to our weekly interviews. Although he insisted he wanted no giftsmy needs are simple, I have all I wanthe swiftly stashed away in his bedside cupboard the packets of soft jubes and occasional bottle of red wine that I would spirit into his room.

Our meetings, which began in June 2013, followed a pattern. He would update me on his healththe heel he injured jumping on cinders in Berlin remained painful on cold daysand perhaps grizzle a little about the nursing home food and the others inability to appreciate poetry. Then would follow our interview, which would last until he grew tired, usually 60 or 70 minutes.

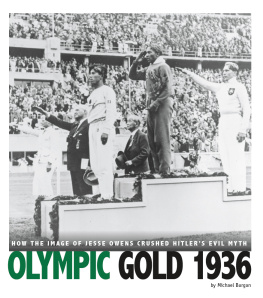

At one interview session, Basil asked me to be sure to try to work what he was about to tell me into the book, because hed spent much of the last days wrestling with his thoughts. This is what he said: Id like it on the record that apart from losing my son Michael, Ive had a most happy life. A good life. Ive represented my country and won medals. Ive loved my family and theyve loved me. So many wonderful things Ive seen and done. My experiences as an Olympian in Berlin helped turn me from an immature boy into a man. After Berlin I knew that life was about more than running and jumping. Although it all happened nearly 80 years ago, I can easily close my eyes and bring to mind that crowd at the stadium yelling, Yess-say O-vens! Yess-say O-vens! and my teammates Jack, Pat, Evelyn, Merv, Harry Cooper, all kids then, and all gone now. The competitors from other nations, many of whom didnt survive the war, and up in his box, with his Nazi mates in their battle dress and the Olympic dignitaries in monkey suits, Adolf Hitler.

We Australians did not all fail individually, as many of us bettered our personal best performance. Where we were lacking was in our preparation and our attitude. There was no intensity, just a belief that if we did our best, whether we won or lost, competed fairly and didnt disgrace Australia, well, that was okay. To me, then and today, that sums up the Olympic spirit, but only in rare cases does it win gold medals.

I didnt look on the political side till I returned home. [In Berlin] I blanked out Adolf Hitlers evil and that he was using us as part of his propaganda. I tried hard to find positives. I was genuinely impressed with what National Socialism was doing for the youth of Germany with such programs as the Strength Through Joy movement which promoted sports and life in the open air. After I came home and things got hot in Europe, the blinkers fell from my eyes and I realised that the Nazis had an ulterior motive for staging the Olympics and that we athletes had been ruthlessly used. Still and all, as long as we were competing well and living up to the Olympic ideals, does it matter? I dont know. I would never swap my Berlin experience for anything. What I do know is that that little fellow Hitler certainly buggered things up.

For all the faults, I put the Olympic Games at their best on a pedestal. Some of the best moments of my life have been Olympic moments, mine and others. Ive always been upset when Ive seen the Olympic ideals of excellence, friendship and respect being undermined by extreme nationalism, politicisation, commercialism and the demand with each Olympics for an ever more extravagant spectacle.

Sometimes Basil would say he wanted to live at least another two years, when he would turn 100 and receive a letter from the Queen. Ive lived so long because Ive tried to be physically and mentally fit. I have good genes. Ill go quietly at 100.

On 1 September, I arrived and found Basils bed empty. I feared the worst, until a nurse told me hed fallen ill with a staph infection and been transferred to hospital for treatment.

When he returned to the home I telephoned Basil and he assured me that he felt well enough to continue our interviews in his room. I arrived on 24 September and found him lying still on his bed with his eyes staring open and his mouth agape. I ran out into the corridor and alerted a nurse: Somethings wrong with Basil, come quick! The nurse gave the old man a hug and he woke. Hes fine, this one, he just likes to nap with his eyes open. Hell be with us forever.

Next page