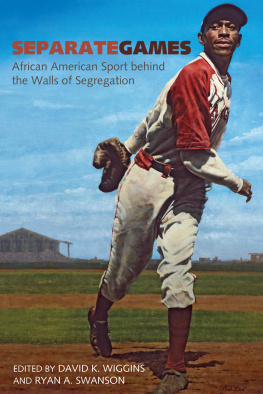

This survey does not pretend to list every source on the fascinating history of race and African American experiences at the Olympics. With that standard caveat out of the way, we offer a list of primary and secondary sources that most influenced our history of Black Mercuries.

PRIMARY SOURCES FROM THE BLACK PRESS

Much of the material for this book is rooted in extensive explorations of primary sources including newspapers and magazines, many of which over past three decades have been digitizeda blessing for researchers. Black newspapers from the 1890s forward include a trove of Olympic details. The Philadelphia Tribune, New York Amsterdam News, New York Age, Baltimore Afro-American, Chicago Defender, and Pittsburgh Courier are rich sources with national readerships that numbered in the tens and even hundreds of thousands. Less well-known Black dailies and weeklies also provide information on Black Olympians, including the Indianapolis Freeman, Cleveland Gazette, Cleveland Call and Post, Chicago Broad-Axe, Washington Bee, Oakland, Californias Western Outlook, Los Angeles California Eagle, and Detroits Michigan Chronicle. The Black press in the South, particularly in the segregation era from the 1890s through the 1960s, provides a unique vantage. Among the key newspapers we used are the Atlanta World, Norfolk New Journal and Guide, Savannah Tribune, Louisiana Weekly (New Orleans), and Houston Observer.

African American journals and magazines also offered rich sources, in particular the Before the Second World War, the NAACPs flagship magazine, The Crisis: A Record of the Darker Races, and the Messenger: New Opinion of the Negro, stand out. A Black Southern journal offered two excellent surveys of Black Olympians in the 1930s by a leading African American promoter of physical fitness, Charles H. Williams. See, Negro Athletes in the Tenth Olympiad, The Southern Workman 61 (November 1932): 449460; Negro Athletes in the Eleventh Olympiad, Southern Workman 66 (February 1937), 4559. In 1945, Ebony (a monthly) and in 1951 Jet (a weekly) began publishing glossy illustrated compendiums for large, national Black readerships, covering the Olympics extensively through the early twenty-first century.

Of course, the white press covered racial issues and Black Olympians extensively, from local dailies to national mass-circulation outlets including the New York Times, Time, Newsweek, and many other publications. A rich reservoir of materials with a digitally searchable archive can be found in the most popular American sports magazine, Sports Illustrated, which began publication in 1954 and has devoted sustained attention to both race and the Olympics.

BLACK OLYMPIANS IN THE THEIR OWN WORDS

Autobiographies of Black Olympians also provide rich insights into their experiences. Some of the most famous Black Mercuries have contributed illuminating autobiographies. That list includes Jesse Owens, with Paul Neimark, Jesse: The Man Who Outran Hitler (New York: Ballantine Books, 1978); Mal Whitfield, Beyond the Finish Line (Washington, D.C.: Whitfield Foundation, 2002); Rafer Johnson and Philip Goldberg, The Best That I Can Be: An Autobiography (New York: Doubleday, 1998); and Michael Johnson, Slaying the Dragon: How to Turn Your Small Steps to Great Feats (New York: Harper, 1996).

Athletes at the center of the 1968 protests have told their stories, including Tommie Smith with David Steele, Silent Gesture: The Autobiography of Tommie Smith (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2007); John Carlos with Dave Zirin, The John Carlos Story (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2011); and Bob Beamon and Milana Walter Beamon, The Man Who Could Fly: The Bob Beamon Story (Columbus, MS: Genesis Press, 1999). The legacy of the 1968 revolt on future games emerges in two fascinating biographies, Vince Matthews with Neil Amdur, My Race Be Won (New York: Charterhouse, 1974); and Eddie Hart with Dave Newhouse, Disqualified: Eddie Hart, Munich 1972, and the Voices of the Most Tragic Olympics (Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 2017).

Another 1968 gold medalist provides a fascinating view of the Olympic struggles not only of Black athletes but also of women competitors from her distinctive perspective as a Black woman in Wyomia Tyus and Elizabeth Terzakis, Tigerbelle: The Wyomia Tyus Story (New York: Akashic, 2019). Black women, including Tyus, have contributed some of the best Olympic autobiographies. See Wilma Rudolph, Wilma: The Story of Wilma Rudolph (New York: New American Library, 1977); and Jackie Joyner-Kersee with Sonja Steptoe, A Kind of Grace: The Autobiography of the Worlds Greatest Female Athlete (New York: Warner Books, 1997). The Tennessee State Tigerbelles coach contributed his perspective in Ed Temple with BLou Carter, Only the Pure in Heart Survive: Glimpses into the Life of a World Famous Olympic Coach (Nashville: Broadman Press, 1980).

Don Barksdale, the first Black Olympian on a basketball team, emerges in his own words in Ron Thomas, They Cleared the Lane: The NBAs Black Pioneers (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2002). The brilliant player who led the U.S. team to basketball gold in 1956 has penned a memoir acclaimed as one finest sport autobiographies ever written, Bill Russell and Taylor Branch, Second Wind: The Memoirs of an Opinionated Man (New York: Random House, 1979). A multiple gold-medalist offers perspectives on the challenges of African Americans to break into swimming in Anthony Ervin and Constantine Markidis, Chasing Water: Elegy of an Olympian (New York: Akashic Books, 2016). Two stellar Black gymnasts offer their accounts in Gabrielle Douglas with Michelle Burford, Grace, Gold, and Glory: My Leap of Faith (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2012); and Simone Biles with Michelle Burford, Courage to Soar: A Body in Motion, A Life in Balance (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2016).

ARCHIVAL MATERIALS

Several archives include not only clip files of newspaper and magazine stories but also official reports, government documents, and illuminating correspondence that shed light on the history of African American Olympians. Among the repositories we visited, several stand out. The United States Olympic Committee Archives in Colorado Springs, Colorado, and the National Archives and Records Administration II facility in College Park, Maryland, have extensive holdings on the subject. The LA84 Foundation Archives in Los Angeles contains records not only on the 1932 and 1984 Olympics, but also information on the broader history of the Olympic movement, including all of the official U.S. Olympic reports since 1920. Official AOC reports for the period from 1896 to 1912 were published as volumes in the Spaldings Athletic Almanac series and are widely available in libraries and online archives.

LA84 also houses an outstanding oral history collection of American Olympians including several from Black athletes. Additional repositories with African American Olympian interviews can be found at the University of Texas at Austin Luther H. Stark Center 1968 Oral History collection. Two websites, The History Makers (https://www.thehistorymakers.org/), and Black Champions (http://repository.wustl.edu/admin_sets/bchamps), offer more interviews. For printed collections of oral histories, John C. Walter and Malinda Iida, Better Than the Best: Black Athletes Speak, 19202007 (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2010) is outstanding.

AFRICAN AMERICANS IN THE OLYMPICSA BRIEF HISTORIOGRAPHY OF ACADEMIC EXPLORATIONS

A variety of secondary sources survey the participation of African American athletes in the Olympics. The original historical chronicle of Black athletes in American history, Edwin Bancroft Henderson,