Neither the British nor the French distributed fish and bread like Jesus did, nor were the Turks kind enough to provide sweets.

Introduction

T hroughout the Republic of Lebanon there are memorials to the past in the form of statues, plaques, monuments, and place names. Some are dedicated to historical events that happened at the site of the memorial, others to prominent personalities. Lebanese and Syrian nationalists hanged by the Turks during World War I are remembered at Martyrs Square in downtown Beirut, and Lebanons international airport is named in honor of former Prime Minister Rafiq Hariri. Throughout the country there are statues of past heroes and hundreds of grottos and sites dedicated to the memory of venerated saints.

One of the more curious memorials is Place Verdun in Beirut, which commemorates a battle that took place almost two thousand miles west of Mount Lebanon. That earth-shattering Franco-German bloodbath, the biggest and longest battle of the Great War, had nothing to do with the people of Beirut and Mount Lebanon though it occurred in 1916, at the same time as Lebanese men, women, and children were dying every day from starvation and disease.

An interesting but gloomy memorial is found near Antelias on the main coastal highway, heading south toward downtown Beirut. It is one of at least four memorials dedicated to the victims of the 1915 Armenian genocide and the survivors who sought refuge in Lebanon.

The Lebanese government has officially recognized the Armenian genocide, but nowhere is there any official memorial to the victims of the World War I famine. Nor is there a national Famine Remembrance Day or any popular history book on the topic. Public documents listing the names of those who died or the number of famine-related deaths do not exist, although undocumented estimates range from one-third to a staggering one-half of the population of Mount Lebanon. One would think that a cataclysm that reportedly claimed tens of thousands of lives through starvation and disease would have been as traumatic to the Lebanese as genocide was to the Armenians and would have warranted some sort of public memorial.

Varying opinions that discuss collective memory are presented by writers in academic journals and books, but they are mostly theoretical if not outright speculative. Among several possible explanations that have escaped scrutiny is the belief that the Famine was one more sordid event in the history of a land that has been plagued with invasion, foreign intervention, economic inadequacy and hardship, making it typical of Lebanons historical experiences. Another explanation is that the number of deaths attributed to the Famine was exaggerated and to those skeptics the subject is not sufficiently significant to warrant discussion or debate, let alone any sort of official memorial.

For these and other reasons, I suspected early on that I might find little information in print about the Famine. Most histories of the Great War focus on the Western and Russian Fronts. Events beyond Europe other than the Armenian genocide and Gallipoli campaign are given scant attention or ignored entirely. Deficiencies in blockade literature are also evident. Those studies describe the consequences of Baltic Sea and Atlantic blockades, but there is no mention of the blockade of Syria-Mount Lebanon and Turkey.

As I looked further, however, I found that indeed there is considerable information about the Famine; the problem was not the quantity of data but its setting. Famine-related accounts are fragmented and scattered throughout many venues; certain history books, newspaper articles, memoirs, diaries, academic journals, doctoral dissertations, oral histories, transcripts of obscure lectures, non-public documents.

Historians of Lebanon tell about the Famine in varying detail, but most of these accounts are brief and some provide no source documentation. This is especially troublesome when one wishes to determine whether a particular story or event is newly discovered information or a variation of an older one.

In The Arab Awakening , George Antonius provides an informative though brief summary of what happened during the Famine. Among the original sources that he cites is a lengthy 1916 New York Times article in which an unnamed witness reported in detail about the Famine and other events occurring in Beirut and Mount Lebanon. Because of its cogent firsthand revelations the article has been cited by other writers as well. The article in its entirety appears in Appendix A.

The largest single body of publicly available Famine-related research to date is found in a 1972 Georgetown University dissertation by Nicholas Z. Ajay, titled Mount Lebanon and the Wilayah of Beirut, 19141918: The War Years . This encyclopedic study, more than eight hundred pages in length, contains an enormous amount of details, interviews, documents, and associated facts. Because of its depth of research it has much information not incorporated into more recent works, making it an invaluable source to this day.

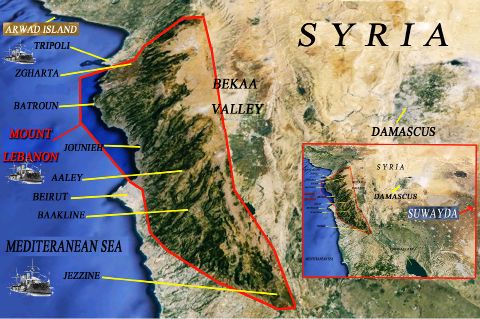

During the Famine years there were two separate governments for the area that we now know as Lebanon: one for Beirut and the areas under its governance and another for Mount Lebanon. This is why both names appear in the title of Ajays dissertation. Prior to the war, one was headquartered within Beirut proper and the other in Mount Lebanon. Shortly after the outbreak of hostilities, Ottoman authorities moved the offices of both governments to Aaley in Mount Lebanon, a few miles east of Beirut, headquarters of the Ottoman military administration and occupation army.

The focal point of this story is the Famine in Mount Lebanon and how it unfolded against the panorama of the Great War and the political decisions and military campaigns that produced this tragedy. Because the Famine was directly affected by events that occurred in Beirut, Greater Syria, and elsewhere beyond Mount Lebanon, they are recounted as part of the story.

To understand the story one needs to be familiar with a variety of participating nations and ethnic groups, some of whom were identified with different names a century ago from those that we generally use today. For example, the people of Mount Lebanon were identified as Syrians until well into the 1940s. In the United States, the ethnic designation Lebanese came into popular usage only after World War II.

The Great War belligerents were divided into two camps, with the Triple Entente or Allies, consisting of Great Britain, France, and Russia, opposing the Central Powers of Germany, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and their allies. In this text the Austro-Hungarian Empire is referred to as Austria. While most of Europe was engulfed in war from 1914 to 1918, some countries remained neutral, such as Spain and Sweden. They both play a role in the Famine story.

The capital of the Ottoman Empire, Constantinople, still carried the name given to it in the year 330, when it became the imperial capital for the Roman Emperor Constantine the Great. In World War I literature it is sometimes referred to as Istanbul or Stambul, but Constantinople did not officially become Istanbul until the Turkish parliament passed legislation to this effect in 1930. In this story the geographical Turkish homeland is referred to as Turkey, Anatolia, or Asia Minor.