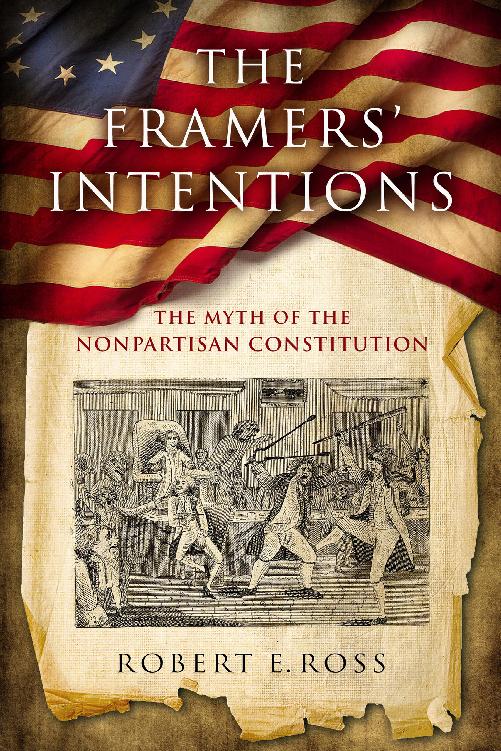

the fr a mers intentions

the

fr amers

intentions

The Myth of the

Nonpartisan Constitution

robert e. ross

University of Notre Dame Press

Notre Dame, Indiana

University of Notre Dame Press

Notre Dame, Indiana 46556

undpress.nd.edu

Copyright 2019 by the University of Notre Dame All Rights Reserved

Published in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Ross, Robert E., 1981, author.

Title: The Framers intentions : the myth of the nonpartisan Constitution / Robert E. Ross.

Description: Notre Dame, Indiana : University of Notre Dame Press,

[2019] | Includes bibliographical references and index. |

Identifiers: LCCN 2019002908 (print) | LCCN 2019015519 (ebook) |

ISBN 9780268105525 (pdf) | ISBN 9780268105518 (epub) |

ISBN 9780268105495 (hardback : alk. paper) |

ISBN 0268105499 (hardback : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Political parties United States History 18th century. |

Political parties United States History 19th century. | Constitutional history United States. | United States. Constitution. 1st Amendment. | United States. Constitution. 12th Amerndment. | Founding Fathers of the United States.

Classification: LCC JK2260 (ebook) |

LCC JK2260 .R67 2019 (print) | DDC 342.73/07 dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019002908

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992

(Permanence of Paper).

This e-Book was converted from the original source file by a third-party vendor.

Readers who notice any formatting, textual, or readability issues are encouraged to contact the publisher at ebooks@nd.edu

C on t e n t s

vi Contents

a c k n o w l e d g m e n t s

This project is the product of countless individuals to whom I owe a debt of gratitude for their efforts on my behalf.

I wish to thank my colleagues and teachers at the University of Hous-ton, where this project began from a question posed in a seminar on political parties, and at Utah State University, where it was finally completed. First and foremost, I am deeply indebted to Jeremy Bailey, who exemplarily embraced the role of adviser and mentor. Jeremy taught me how to be a scholar, and I constantly recognize his influence on my work.

I express my gratitude to Michael Zuckert, Jeffrey Church, and Richard Murray, who read various versions of the manuscript and provided in-valuable feedback. I am grateful for Andrea Eckelman, Sarah Mallums, Bruce Hunt, Roger Abshire, Marcia Beyer, Luke Williams, and Markie McBrayer, who offered encouragement and support through the initial stages of the project. At Utah State University, I owe Peter McNamara, Tony Peacock, Damon Cann, Michael Lyons, and Josh Ryan my gratitude for pushing me to complete the project.

The University of Notre Dame Press has made this project a reality.

I owe thanks to my editor, Eli Bortz, the staff, and the reviewers: all of you made valuable comments that vastly improved the manuscript. Publius: The Journal of Federalism has given permission to reprint a portion of chapter 6, which is a revision of Federalism and the Electoral Col ege: The Development of the General Ticket Method for Selecting Presidential Electors, Publius 46, no. 2 (2016): 14769. Likewise, Polity has given permission to reprint a portion of chapter 7, which is a revision of vii

viii Acknowledgments

Recreating the House: The 1842 Apportionment Act and the Whig Partys Reconstruction of Representation, Polity 49, no. 3 (2017): 40833.

Finally, I would not have completed this project without the support of my family. My parents, Charles and Sandra Ross, offered support and encouragement no matter how obscure my project seemed to them. Likewise, Harold and Teresa Kunz provided as much support as in-laws could possibly give. To my children, Nathaniel and Scarlett, thank you for patiently waiting for me to finish working before requesting my return to the good life. Finally, my wife Erin was my constant amid persistent uncertainty. Thank you for loving me through it all.

I n t r o d u c t i o n

Antipartyism and the Constitution

Reassessing the Constitution-against-Parties Thesis It is well known by party scholars that many members of the founding generation held deep antiparty sentiments and aimed to design a constitutional system that would exclude political parties. The Constitution is silent on parties, and most scholars have interpreted this as a hostile silence.

The new constitutional system was intended to include a level of popu lar sovereignty but not through mass participation by way of political parties.

Rather, institutions were designed to limit popular influence and mute party competition.1 Competition among various interests and institutional features like the division and separation of powers would constrain and contain party conflict and dialogue.2 With the Constitutions ratification, democracy in the United States was intended to proceed without the intervention of political parties. However, political parties developed quickly, and the intention of designing a constitutional government without political parties was short-lived. Even more to the point, many of the founders who expressed antiparty sentiments, such as James Madison and Thomas Jefferson, were also central in creating the first political parties.

Political parties have an unsettled place in American constitutionalism 1

2 The Framers Intentions

because they are deemed useful, if not necessary, to politics, even for those who seemingly despise them.

Contemporary society faces the same party paradox as the founding generation. For all the claims against partyism and partisan obstinacy, parties are embraced because they provide salutary benefits for the political process at every level of government. While political parties and an institutionalized party system were never intended to be a prominent feature in the American constitutional order, American politics are fundamentally structured and organized by political parties and a system of partisan competition for elected offices.3 Unlike any other institution in American politics, political parties have the capacity to divide while also providing a mechanism for unity across the vast nation. At the national and local levels, parties play a pivotal role in electing candidates and recruiting political leadership, educating citizens by transmitting political information and values, and governing by organizing individuals and groups into majorities. Yet parties threaten the overall needs of the nation because they represent only partial or special interests. As James Madison warned, The public good is disregarded in the conflicts of rival parties, and... measures are too often decided, not according to the rules of justice and the rights of the minor party, but by the superior force of an interested and overbearing majority.4 Political parties are institutionalized features of American constitutionalism, and attempts to promote or strengthen parties and the party system because of their utility must be reconciled with the clear attempts to eliminate or circumscribe their influence in politics and vice versa.

Given the promise and peril of partyism for politics, the purpose of this book is to understand how political parties became deeply entrenched in a constitutional order that was intended to work against them. The notion that the Constitution was intended to work against political parties, or what the historian Richard Hofstadter calls the Constitution-against-parties thesis,5 has long been a pil ar of American political and constitutional development. The primary aim of this book is to address how the framers interpreted the Constitution in relation to the emergence of the first political parties in the United States. To a large extent, the turn to political parties came in response to the Constitutions promise of popular sovereignty and majority rule. Political actors interpreted the Constitution and constructed constitutional meaning to

Next page