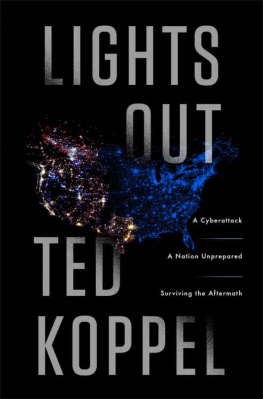

More Praise for

LIGHTS OUT

A bold enumeration of the challenges posed by the digital age; an appeal to safeguard new instruments of human flourishing by studying the ways in which they could be exploited.

Henry A. Kissinger

Try to imagine what a malevolent government, armed with the latest computer sophistication, could do to another nations complex and entirely digital-dependent economy and social infrastructure. Fortunately, Ted Koppel has imagined it for us. We have been warned.

George F. Will

In Lights Out , Ted Koppel uses his profound journalistic talents to raise pressing questions about our nations aging electrical grid. Through interview after interview with leading experts, Koppel paints a compelling picture of the impact cyberattacks may have on the grid. The book reveals the vulnerability of perhaps the most critical of all the infrastructures of our modern society: the electricity that keeps our modern society humming along.

Marc Goodman, author of Future Crimes

When the lights go out after the cyberattack, this is the book everyone will read.

Richard A. Clarke, author of Cyber War and former National Coordinator for Security, Infrastructure Protection, and Counter-terrorism

Copyright 2015 by Edward J. Koppel

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Crown Publishers, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

www.crownpublishing.com

CROWN and the Crown colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available upon request.

ISBN9780553419962

eBook ISBN9780553419979

Cover design by Tal Goretsky

Cover photograph by NOAA/Science Source

v4.1_r1

a

To our grandchildren:

Jake and Dylan, Aidan, Alice and Annabelle, Cole and Grace Ann(e). Heres hoping that Opi got it wrong .

CONTENTS

Warfare 2.0

Everyone is not entitled to his own facts. DANIEL PATRICK MOYNIHAN

Darkness.

Extended periods of darkness, longer and more profound than anyone now living in one of Americas great cities has ever known.

As power shuts down there is darkness and the sudden loss of electrical conveniences. As batteries lose power, there is the more gradual failure of cellphones, portable radios, and flashlights.

Emergency generators provide pockets of light and power, but there is little running water anywhere. In cities with water towers on the roofs of high-rise buildings, gravity keeps the flow going for two, perhaps three days. When this runs out, taps go dry; toilets no longer flush. Emergency supplies of bottled water are too scarce to use for anything but drinking, and there is nowhere to replenish the supply. Disposal of human waste becomes a critical issue within days.

Supermarket and pharmacy shelves are empty in a matter of hours. It is a shock to discover how quickly a city can exhaust its food supplies. Stores do not readily adapt to panic buying, and many city dwellers, accustomed to ordering out, have only scant supplies at home. There is no immediate resupply, and people become desperate.

For the first couple of days, emergency personnel are overwhelmingly engaged in rescuing people trapped in elevators. Medicines are running out. Home care patients reliant on ventilators and other medical machines are already dying. One city has hoisted balloons marking the sites of generators, hauled out of storage to serve new emergency centers. Almost everyone needs some kind of assistance, and no one has adequate information.

The city has flooded the streets with police to preserve calm, to maintain order, but the police themselves lack critical information. People are less concerned with what exactly happened than with how long it will take to restore power. This is a society that regards information, the ability to communicate instantly, as an entitlement. Round-the-clock chatter on radio and television continues, but theres little new information and a diminishing number of people still have access to functioning radios and television sets. The constant barrage of messages that once flowed between iPhones and among laptops has sputtered to a trickle. The tissue of emails, texts, and phone calls that held our social networks together is tearing.

There is a growing awareness that this power outage extends far beyond any particular city and its suburbs. It may extend over several states. Tens of millions of people appear affected. Fuel is beginning to run out. Operating gas stations have no way of determining when their supply of gasoline and diesel will be replenished, and gas stations without backup generators are unable to operate their pumps. Those with generators are running out of fuel and shutting down.

The amount of water, food, and fuel consumed by a city of several million inhabitants is staggering. Emergency supplies are sufficient only for a matter of days, and official estimates of how much help is needed and how soon it can be delivered are vague, uncertain. The majority who believed that power outages are limited in duration, that help always arrives from beyond the edge of darkness, is undergoing a crisis of conviction. The assumption that the city, the state, or even the federal government has the plans and the wherewithal to handle this particular crisis is being replaced by the terrible sense that people are increasingly on their own. When that awareness takes hold it leads to a contagion of panic and chaos.

There are emergency preparedness plans in place for earthquakes and hurricanes, heat waves and ice storms. There are plans for power outages of a few days, affecting as many as several million people. But if a highly populated area was without electricity for a period of months or even weeks, there is no master plan for the civilian population.

Preparing for doomsday has its own rich history in this country, and predictions of the apocalypse are hardly new to people of my generation. We lived for decades with the assumption that nuclear war with the Soviet Union was a real possibility. We learned some useful lessons. (Well ramble through the age of bomb shelters and civil defense in a later chapter.) Ultimately, Moscow and Washington came to the conclusion that mutual assured destruction, holding each other hostage to the fear of nuclear reprisal, was a healthier approach to coexistence than mass evacuation or hunkering down in our respective warrens of bomb shelters in the hopes of surviving a nuclear winter.

We are living in different times. Whether the threat of nuclear war has actually receded or whether weve simply become inured to a condition we cannot change, most of us have finally learned to stop worrying and love the bomb. In reality, though, the ranks of our enemies, those who would and can inflict serious damage on America, have grown and diversified. So many of our transactions are now conducted in cyberspace that we have developed dependencies we could not even have imagined a generation ago. To be dependent is to be vulnerable. We have grown cheerfully dependent on the benefits of our online transactions, even as we observe the growth of cyber crime. We remain largely oblivious to the potential catastrophe of a well-targeted cyberattack.

Next page