Table of Contents

Copyright 2006 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

First Harvard University Press paperback edition, 2008

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Pei, Minxin.

Chinas trapped transition : the limits of developmental autocracy / Minxin Pei.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-674-02195-2 (cloth: alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-674-02754-1 (pbk.)

1. DemocracyChina. 2. ChinaPolitics and government1976-2002-

3. ChinaEconomic policy1976-2000. 4. ChinaEconomic policy2000I. Title

JQ1516.P44 2006

320.951dc22

2005052762

To Samuel P. Huntington

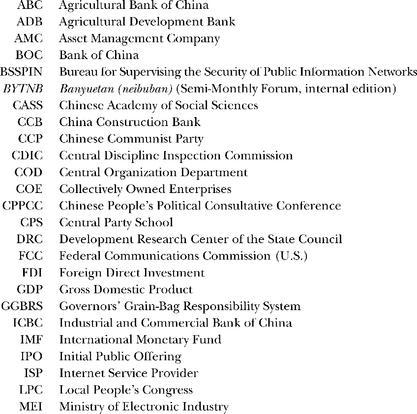

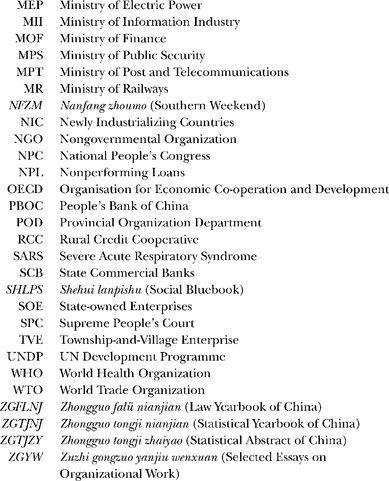

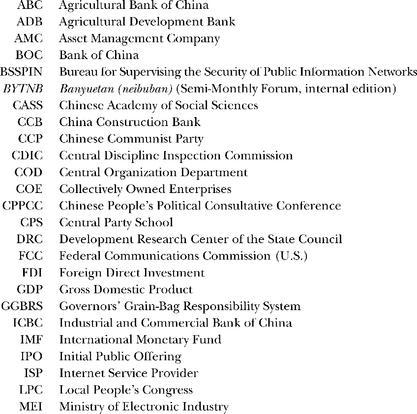

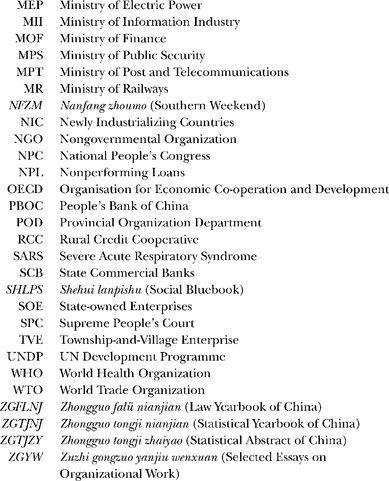

Abbreviations

Introduction

THE ECONOMIC MODERNIZATION DRIVE that China launched at the end of the 1970s ranks as one of the most dramatic episodes of social and economic transformation in history. This process occurred in a unique political and economic context: a simultaneous transition from a state-socialist economic system and a quasi-totalitarian political system. Despite temporary setbacks, brief periods of high political tension, episodes of economic instability, and numerous conservative counterattacks, the two-decade-old, and ongoing, transition has dramatically altered the Chinese economic, social, and political landscapes.

In measurable terms of economic development and social change, Chinas achievement has been unprecedented in speed, scale, and scope. Rapid economic growth has not only vastly improved the economic well-being of the countrys 1.3 billion people, but also has (fundamentally altered the structure of Chinese society. Additionally, as market-oriented reforms have made the Chinese economy less state-centered and more decentralized, economic development has turned Chinese society from one that was once tightly controlled by the state, into one that is increasingly autonomous, pluralistic, and complex. During this period, Chinas integration with the international community proceeded along several fronts. Trade and investment spearheaded this integration as China ascended from a negligible player in the world economy prior to reform, to a leading trading state and one of the most favored destinations for foreign direct investment (FDI). Chinas integration with the outside world has also taken place in other important areas, such as membership and participation in various international institutions, advancement in key bilateral ties, and educational and cultural exchanges with the West.

Most of these momentous changes have been captured by statistics measuring various aspects of Chinese society and economy. The aggregate size of the Chinese economy in 2002 was more than eight times the size it was in 1978.

Rapid economic growth has greatly expanded Chinese citizens access to information and increased their physical mobility. About two thousand Chinese people shared a telephone line in 1978; in 2002, a fixed telephone line was available for roughly every six people and, in addition, about one mobile telephone was available for every six people. In 1978, three out of one thousand households owned a black-and-white television set. In 2002, there were 126 color television sets in every 100 urban households and 60 color sets in every 100 rural households. In 1978, on average, only 180 million domestic long-distance calls were made (about one for every five people); in 2001, 22 billion such calls were made17 calls per capita. From 1978 to 2002, the number of newspaper copies printed tripled, and the number of titles of books published had risen eleven-fold. Internet users, barely 160,000 in 1997, numbered 79 million in 2003. Such data suggest that access to information for average Chinese citizens has risen by several orders of magnitude on a per capita basis within a quarter century.

The rise in physical mobility is equally impressive. Passengers transported by various means rose 533 percent in this period, from 2.54 billion in 1978 to 16 billion in 2002. Measured in per capita terms, increase in physical mobility was close to 500 percent. Significantly, an increasingly large number of Chinese citizens gained the freedom to travel overseas. In 1978, few ordinary citizens were allowed this privilege. In 2002, 16.6 million Chinese traveled abroad.

An importantif not inevitableby-product of economic reform was the significant decline of the states role in the economy. In terms of industrial output, the share of state-owned enterprises fell from nearly 78 to 41 percent from 1978 to 2002, while the share of the private sector (including foreign-invested firms) rose from 0.2 to 41 percent. These figures indicate that the states control over the economic and social activities of its citizens has greatly eroded as a direct result of its declining presence in the economy.

One of the defining features of Chinas economic reform is its integration with the world economy.

Chinas integration into the international community has not been limited to trade and investment. Almost equally significant are the extensive educational, social, and cultural links with the West established during the reform period through the training of hundreds of thousands of Chinese students and visiting scholars in Western institutions of high learning, the appointment of tens of thousands of Western experts in Chinese universities, and through tourism and popular culture. Although it is difficult to quantify precisely the impact of such a multifaceted process of integration on Chinese society and politics, it is highly likely that the effects of this transformation have contributed to changes in values, tastes, and lifestyles that have occurred since the late 1970s.

Chinas Lagging Political Development

Juxtaposed against such massive, and largely positive, economic and social changes, however, is Chinas political system. Despite more than two decades of rapid socioeconomic changes, the core features of a Leninist party-state remain essentially unchanged.

In his speech at a small group meeting of the 16th Congress of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in November 2002, Li Rui, an outspoken liberal party member and former secretary to Mao Zedong, offered an apt assessment of Chinas political progress:

Since China began its transition to a market economy, our national strength has been rising steadily, and we have gained undisputed great progress. But these problems remain: excessively slow pace in the reform of the political system, the lagging development of democracy, the weakness of the rule of law, and the resultant pervasive corruption.

Lagging political development will endanger the CCPs own survival, Li warned:

Chinese and foreign histories prove that autocracy is the source of political turmoil. As the collapse of the Soviet Union shows, the root cause is autocracy. Modernization is possible only through democratization. This is the trend in the world in the twentieth century, especially since the Second World War. Those who follow this trend will thrive; those who fight against this trend will perish. This rule applies to every countryand every party.

Chinas lagging political openness is reflected in the low scores the country receives from several widely used international indexes. The Polity IV Project consistently rates China as one of the most authoritarian political systems in the world.

Various measures of governance confirm the underdevelopment of key public institutions in China. In a quality of governance ranking compiled by Jeff Huther and Anwar Shah of the World Bank in 1998, China was placed in the bottom third of the eighty countries ranked. China received a score of 39, similar to that given to poorly governed countries such as Egypt, Kenya, Cameroon, Honduras, Indonesia, Pakistan, and Nigeria.

Next page