I wish to thank Jean Casella for all her help throughout this project; Judy Davis who kept tabs on preparation of the manuscript; and my wonderful interns who worked years on this book: Gabrielle Jackson, Cassandra Lewis, Rouven Guissaz, Kate Cortesi, Ariston Lizabeth Anderson, Sandra Bisin, Joanna Khenkine, Phoebe St John, Sarah Park, Meritxell Mir, Michael Ridley, Josh Hersh, Caroline Ragon, Josh Saltzman, Rebecca Winsor, and Adrian Brune. I am also grateful to Curtis Lang, Phillip Levy and Bridge Street Books, Adrienne Fugh-Berman, Alpha Diallo, Jeffrey St. Clair, Camelia Fard, Bo Eddy, Cindy Mellon, Alysa Zeltzer, Mark Ritchie, Al Krebs, Charlie Arnot, Kris Jacobs, Rob Weissman, John Richard and the Center for Study of Responsive Law, Public Citizen, Tyson Slocum, Ronnie Cummins, Russell Mokhiber, David Ridgeway, Mike McCarthy. I want to thank Valerie MillhoUand, Mark Mastromarino, and the most helpful staff at the Duke University Press. And I am especially grateful to Patricia Ridgeway.

INTRODUCTION

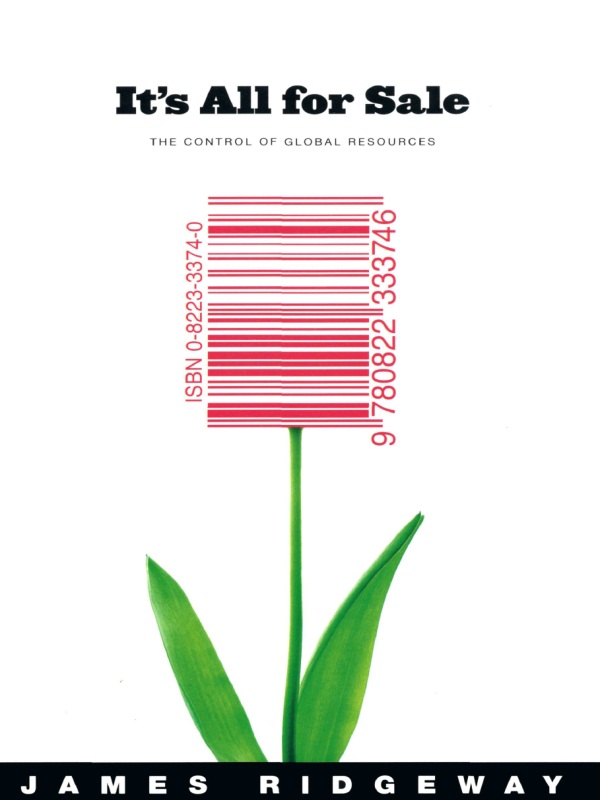

Commodities seldom draw much attention in the interpretation of todays world events. And yet they have played an important role in the evolution of colonialism and empire, and in the waging of small and large wars. They have influenced the flow of migration and emigration. People were enslaved to exploit commodities. They have always been at the heart of things.

The earliest known trade routes across the world, which brought distant and disparate cultures into contact, were created in order to obtain and transport new commodities. The ancient Silk Road from Japan to the Mediterranean was one. Another was the route to trade pepper, which in some places was treated as money. Marco Polo and Columbus are famous as explorers, but they were also businessmenpushed on perhaps by their adventurous spirits, but also by the quest for new sources and routes for the trade of valuable commodities. (So too were the Chinese, great traders of the times, who it now seems may have beat out the Europeans in the discovery of the Americas.)

Colonialism was justified by Western ideas of racial, religious, and civil superiority, but it was often driven by the quest for natural resources, the raw materials of the Industrial Revolution. Slavery was supported by a system that turned human beings into commodities, to be handled no differently from the molasses and rum that completed the famous eighteenth-century triangle trade route. In the nineteenth century, the British manufactured textiles and sent them to India, then refilled the ships with opium and dispatched them to China. The money they received for opium was used to buy tea, which was sent to England. A hundred years later, the United States supported Pinochets coup against Salvador Allende in Chile in part because of his nationalization of the nations big copper deposits. While a determination to contain communism and Soviet power was certainly the paramount motivation behind Americas wars and covert actions in the developing world during the cold war years, such motivations were often closely intertwined with issues of resource control. The Cuban revolution, for example, reduced Americas supply of nickel, forcing the United States to quickly find other sources of this crucial metal. The same event was used to justify enormous subsidies to the American sugar industry, as sugar was deemed a commodity necessary to national security, too precious to justify reliance upon volatile Caribbean and Latin American suppliers.

The linkage of commodities to national security has been used to justify military interventions and deployments to protect essential routes of trade, as well as supplies of commodities. In the 1980s the U.S. military began to talk about protecting certain strategic trade routes around the world, the most prominent running from the Persian Gulf around the Horn of Africa to North America. The Strait of Malacca, through which oil tankers passed from the Middle East to Southeast Asia and Japan, was another. The American invasion of Panama in 1989 was based on the determination of the United States to control a pivotal trade route. And at the beginning of the twenty-first century, military planners were studying how to protect the Northwest Passagestretching from the North Atlantic across the Arctic to the Pacific Oceanwhich connects Europe to Asia more directly than those trade routes leading through the Panama Canal or around the tip of South America. Global warming and melting glaciers have opened up the Northwest Passage throughout the year.

The struggle for control of resources took a new turn with the end of the cold war. During the cold war the United States and the old Soviet Union had supported opposing groups of freedom fighters struggling to control nations in Africa, Latin America, and Asia. These groups vied for control of a countrys governmentand by implication its resourcesin the interests of nation building. Today the situation is quite different. Many contemporary conflicts in the developing world take place below or outside the level of nation states. A study by the United Nations in 2002 revealed networks of rogue army officers and so-called warlords, errant forces on the loose and allied with cynical politicians and transnational corporations to control and exploit forests, as well as diamonds, copper, and other minerals. In many cases, formal political considerations have been virtually removed from the equation, or they take a back seat to the bald fight over lucrative commodities. In American terms, the situation harks back to the days of the nineteenth-century robber barons and their henchmen, who were a law unto themselves in the timber and gold-mining camps of the West.

When regional strife in seven African states brought their armies together in the Congo, the elite officers of the Zimbabwean army began profiting from the mineral trade there. When that army withdrew, the officers signed a secret deal with politicians in the Congo to continue the exploitation of diamonds.

As they did so the revolutionary quarrels of the cold war were replaced by non-ideological mercenary armies whose main interest was making money. An investigation by the Center for Public Integrity in Washington found more than 90 military companies operating in no countries. These armies for hire are to some extent the modern equivalent of the French Foreign Legion.

These corporate armies, providing services normally carried out by a national military force, offer specialized skills in high-tech warfare, including communications and signals intelligence and aerial surveillance, as well as pilots, logistical support, battlefield planning and training. They have been hired both by the governments and multinational corporations to further their policies or protect their interests. Indeed, one large corporation owns a private military company as a subsidiary. These military companies thrive below the radar in the worldwide small-arms bazaar, where a firm can outfit itself with secondhand Russian gear or pirated arms from one of the former Soviet-bloc nations in central and eastern Europe. Small arms do not amount to much in terms of the overall arms marketperhaps 10 percent of the totalbut they do the work in most of the wars and are responsible for virtually all the killing. In real terms, these are the true weapons of mass destruction.