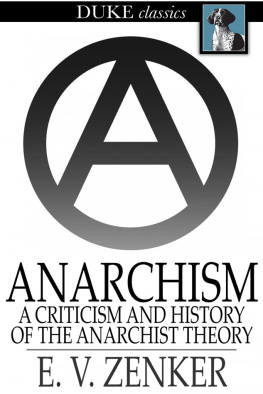

Two Cheers for Anarchism

Two Cheers for Anarchism

Six Easy Pieces on Autonomy, Dignity, and Meaningful Work and Play

JAMES C. SCOTT

Princeton University Press

Princeton & Oxford

Copyright 2012 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

press.princeton.edu

All Rights Reserved

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Scott, James C.

Two cheers for anarchism : six easy pieces on autonomy, dignity, and meaningful work and play / James C. Scott.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-691-15529-6 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Anarchism. I. Title.

HX826.S35 2012

335.83dc23 2012015029

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Garamond Pro

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Contents

Illustrations

Preface

The arguments found here have been gestating for a long time, as I wrote about peasants, class conflict, resistance, development projects, and marginal peoples in the hills of Southeast Asia. Again and again over three decades, I found myself having said something in a seminar discussion or having written something and then catching myself thinking, Now, that sounds like what an anarchist would argue. In geometry, two points make a line; but when the third, fourth, and fifth points all fall on the same line, then the coincidence is hard to ignore. Struck by that coincidence, I decided it was time to read the anarchist classics and the histories of anarchist movements. To that end, I taught a large undergraduate lecture course on anarchism in an effort to educate myself and perhaps work out my relationship to anarchism. The result, having sat on the back burner for the better part of twenty years after the course ended, is assembled here.

My interest in the anarchist critique of the state was born of disillusionment and dashed hopes in revolutionary change. This was a common enough experience for those who came to political consciousness in the 1960s in North America. For me and many others, the 1960s were the high tide of what one might call a romance with peasant wars of national liberation. I was, for a time, fully swept up in this moment of utopian possibilities. I followed with some awe and, in retrospect, a great deal of naivet the referendum for independence in Ahmed Skou Tours Guinea, the pan-African initiatives of Ghanas president, Kwame Nkrumah, the early elections in Indonesia, the independence and first elections in Burma, where I had spent a year, and, of course, the land reforms in revolutionary China and nationwide elections in India.

The disillusionment was propelled by two processes: historical inquiry and current events. It dawned on me, as it should have earlier, that virtually every major successful revolution ended by creating a state more powerful than the one it overthrew, a state that in turn was able to extract more resources from and exercise more control over the very populations it was designed to serve. Here, the anarchist critique of Marx and, especially, of Lenin seemed prescient. The French Revolution led to the Thermadorian Reaction, and then to the precocious and belligerent Napoleonic state. The October Revolution in Russia led to Lenins dictatorship of the vanguard party and then to the repression of striking seamen and workers (the proletariat!) at Kronstadt, collectivization, and the gulag. If the ancien rgime had presided over feudal inequality with brutality, the record of the revolutions made for similarly melancholy reading. The popular aspirations that provided the energy and courage for the revolutionary victory were, in any long view, almost inevitably betrayed.

Current events were no less disquieting when it came to what contemporary revolutions meant for the largest class in world history, the peasantry. The Viet Minh, rulers in the northern half of Vietnam following the Geneva Accords of 1954, had ruthlessly suppressed a popular rebellion of smallholders and petty landlords in the very areas that were the historical hotbeds of peasant radicalism. In China, it had become clear that the Great Leap Forward, during which Mao, his critics silenced, forced millions of peasants into large agrarian communes and dining halls, was having catastrophic results. Scholars and statisticians still argue about the human toll between 1958 and 1962, but it is unlikely to be less than 35 million people. While the human toll of the Great Leap Forward was being recognized, ominous news of starvation and executions in Kampuchea under the Khmer Rouge completed the picture of peasant revolutions gone lethally awry.

It was not as if the Western bloc and its Cold War policies in poor nations offered an edifying alternative to real existing socialism. Regimes and states that presided dictatorially over crushing inequalities were welcomed as allies in the struggle against communism. Those familiar with this period will recall that it also represented the early high tide of development studies and the new field of development economics. If revolutionary elites imagined vast projects of social engineering in a collectivist vein, development specialists were no less certain of their ability to deliver economic growth by hierarchically engineering property forms, investing in physical infrastructure, and promoting cashcropping and markets for land, generally strengthening the state and amplifying inequalities. The free world, especially in the Global South seemed vulnerable to both the socialist critique of capitalist inequality and the communist and anarchist critiques of the state as the guarantor of these inequalities.

This twin disillusionment seemed to me to bear out the adage of Mikhail Bakunin: Freedom without socialism is privilege and injustice; socialism without freedom is slavery and brutality.

An Anarchist Squint, or Seeing Like an Anarchist

Lacking a comprehensive anarchist worldview and philosophy, and in any case wary of nomothetic ways of seeing, I am making a case for a sort of anarchist squint. What I aim to show is that if you put on anarchist glasses and look at the history of popular movements, revolutions, ordinary politics, and the state from that angle, certain insights will appear that are obscured from almost any other angle. It will also become apparent that anarchist principles are active in the aspirations and political action of people who have never heard of anarchism or anarchist philosophy. One thing that heaves into view, I believe, is what Pierre-Joseph Proudhon had in mind when he first used the term anarchism, namely, mutuality, or cooperation without hierarchy or state rule. Another is the anarchist tolerance for confusion and improvisation that accompanies social learning, and confidence in spontaneous cooperation and reciprocity. Here Rosa Luxemburgs preference, in the long run, for the honest mistakes of the working class over the wisdom of the executive decisions of a handful of vanguard party elites is indicative of this stance. My claim, then, is fairly modest. These glasses, I think, offer a sharper image and better depth of field than most of the alternatives.

Next page