About the Author

Alexander Stilles first book, Benevolence and Betrayal: Five Italian Jewish Families Under Fascism, was chosen by the Times Literary Supplement as one of the best books of 1992, and received the Los Angeles Times Book Award for history. From 1990 until 1993, Stille reported on Italy for US News and World Report, The Boston Globe and the Toronto Globe and Mail, while contributing long articles to The New Yorker and The Atlantic. He lives in New York.

BY ALEXANDER STILLE

Benevolence And Betrayal:

Five Italian Jewish Families Under Fascism

Excellent Cadavers:

The Mafia And The Death Of The First Italian Republic

Alexander Stille

E XCELLENT

C ADAVERS

The Mafia and the Death of

the First Italian Republic

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

Version 1.0

Epub ISBN 9781446418963

www.randomhouse.co.uk

Published by Vintage 1996

10 9

Copyright Alexander Stille 1995

The right of Alexander Stille to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988

First published in Great Britain by

Jonathan Cape Ltd, 1995

Vintage

Random House, 20 Vauxhall Bridge Road,

London SW1V 2SA

The Random House Group Limited Reg. No. 954009

www.randomhouse.co.uk

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

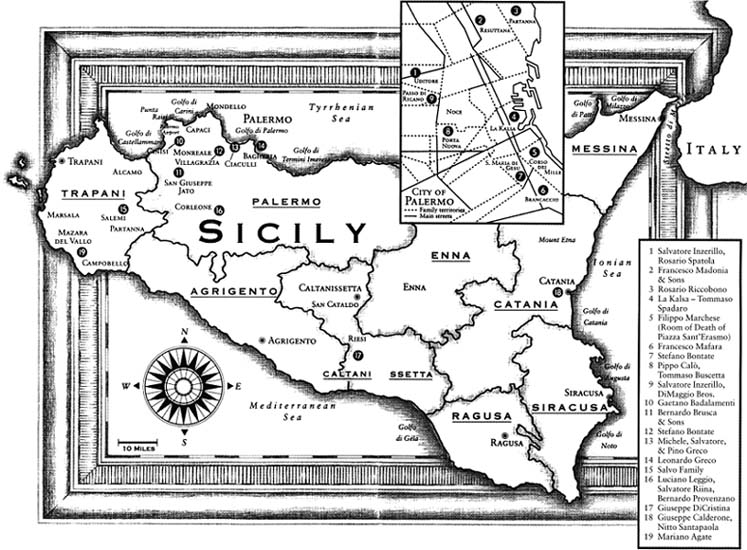

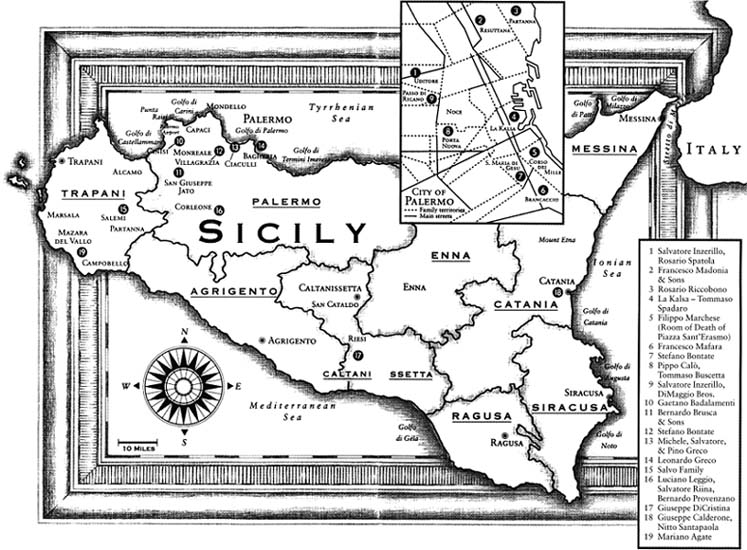

Map design by Bette Duke

For Sarah, Vittorio and Sesa

and in memory of Giovanni Falcone, Paolo Borsellino

and the many other courageous public servants

who have died working in Sicily

CONTENTS

Giovanni Falcone and Paolo Borsellino

(Tony Gentile/Laura Ronchi)

PROLOGUE

I n 1876, a young member of parliament from Tuscany, Leopoldo Franchetti, traveled to Sicily to report on the strange island that had quickly become the most troubled and recalcitrant part of the newly united Italian state. Franchetti was enchanted by the beauty of Palermo, the majesty of the baroque palaces, the exquisite courtesy and hospitality of the people, the languorous, sunny weather, the exotic palm trees and the intoxicating perfume of the orange and lemon blossoms of the Conca dOros fertile citrus groves.

Someone who had just arrived might well believe that Sicily was the easiest and most pleasant place in the entire world. But if [the traveler] stays a while, begins to read the newspapers and listens carefully [he wrote], bit by bit everything changes around him. He hears that the guard of that orchard was killed with a rifle shot coming from behind that wall because the owner hired him rather than someone else. Just over there, an owner who wanted to rent his groves as he saw fit heard a bullet whistle past his head in friendly warning and afterwards gave in. Elsewhere, a young man who had dedicated himself to setting up nursery schools in the outskirts of Palermo was shot at because certain people who dominate the common people in that area, feared that, by benefiting the poorer classes, he would

The perfume of orange and lemon blossoms began to smell of corpses during one of my first trips to Palermo. I went to visit Domenico Signorino, one of the prosecutors who worked on the maxi-trial of Palermothe largest mafia trial in history. Signorino appeared more open and cordial than most prosecutors, especially in Sicily. During a long, pleasant interview, he spoke with great nostalgia and affection about the trial and of his colleagues who had been killed in the war against the mafia. A few days later, I saw Signorinos photograph on the front page of the Palermo newspaper Giornale di Sicilia with the headline: Palermo judge suspected of collusion with the mafia. Two days after that, Judge Signorino took a pistol and shot himself.

It is still not clear whether Judge Signorino was guilty or not. The mafioso who accused Signorino has proven a reliable witness and it seems hard to believe that someone with a clear conscience would commit suicide. But the prosecutors who worked with Signorino swear by his innocence, saying that he had a fragile psyche and insisting that the trauma of public humiliation for a person used to universal respect and approbation can be overwhelming. Some also found it highly suspicious that of the five judges accused of collusion only one name, Signorino, had been leaked to the press. Perhaps Signorino was the victim of a cleverly orchestrated maneuver.

People in Sicily were unsure which possible scenario was worse: that a judge entrusted with the most delicate mafia cases had sold himself to the enemy or that an honest man had been destroyed by an occult hand. Some suggested a third possibility, that Signorino was not guilty of outright collusion but that he had committed some impropriety, accepted some favor, met or knew certain people of dubious reputation, which would invariably create an appearance of guilt with which he could not live. We will probably never know. The case was closed with the death of the suspect, taking its place among the infinite mysteries of Palermo.

Sicily is a place where almost nothing is what it seems. A few days after meeting Signorino, I went to interview Palermos new police chief, who appeared to be an energetic crime fighter, having recently seized the assets of one of the citys main mafia clans. Several months later, he, too, was accused of having taken bribes when he worked in Naples. No one knows what to believe.

Survivors of twenty-five hundred years of foreign invasions and of countless violent and corrupt rulers, Sicilians are a skeptical people. When I asked a Sicilian friend why he didnt trust a local politician with a reputation as an outspoken anti-mafia crusader, he replied: Hes alive, isnt he? If hed really done anything against the mafia, hed already be dead.

Death is the only certain truth. It lifts the disguiseif only brieflyfrom the Pirandellian world of Sicilian politics, where appearance and reality are easily confused and where the face of the mafia may hide behind the respectable mask of lawyer, judge, businessman, priest or politician.

A body found on the sidewalk can reveal secret alliances or conflicts, economic interests or changes in strategy. The notion that only the best investigators are killed is a brutal and often unfair equation for the living: when one Palermo police officer miraculously survived an ambush in which two others died, he was suspected of collusion, a taint that was not removed from his name until the mafia killed him a few years later. The importance of a given prosecutor or politician may not become fully apparent until he is gone.