INTO THE HEART OF THE MAFIA

DAVID LANE has written for the Guardian and the Financial Times, and since1994 has been The Economists business and finance correspondent for Italy. His last book was the highly regarded Berlusconis Shadow (2004). He has lived in Rome since 1972.

Also by David Lane

BERLUSCONIS SHADOW: CRIME, JUSTICE AND THE PURSUIT OF POWER

Damning a withering indictment of crony capitalism, executive thuggery and government incompetence Phil Edwards, Independent

An outstanding example of political writing on Italy both engrossing and deeply worrying John Dickie, Literary Review

The most lucid reading and interpretation of Berlusconi La Repubblica

His book sober, precise, meticulously researched is full of such extraordinary and disquieting facts and events that were it not for Lanes long knowledge of Italy they would be hard to believe both impressive and enjoyable to read Caroline Moorehead, Spectator

INTO THE HEART OF THE MAFIA

A Journey through the Italian South

DAVID LANE

This paperback edition published in 2010

First published in Great Britain in 2009 by

PROFILE BOOKS LTD

3a Exmouth House

Pine Street

Exmouth Market

London EC1R 0JH

www.profilebooks.com

Copyright David Lane, 2009, 2010

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Typeset in Goudy Old Style by MacGuru Ltd

info@macguru.org.uk

Printed and bound in Great Britain by

Bookmarque, Croydon, Surrey

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 84668 135 6

eISBN 978 1 84765 199 0

For my wife Franca and in memory of her parents Michele and Angelina three fine southerners

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Mysteries and Mafiosi

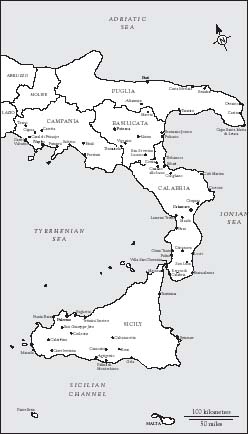

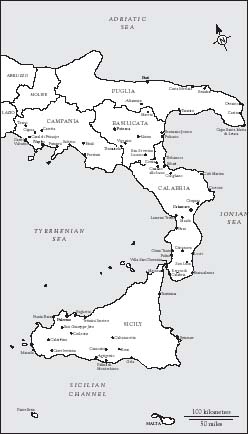

THIS IS A BOOK about Italys home-bred Mafias: Sicilys Cosa Nostra; the Camorra in Naples and Campania, the region around it; Calabrias Ndrangheta; and the Sacra Corona Unita in the Apulian heel. It is a book about crime: murder and mafia wars; extortioners and their victims; the trafficking of arms, drugs and people; and the crooked politicians and businessmen whose complicity helps the Mafia thrive.

The Mafia is the thread, from Gela on Sicilys southern coast, through Corleone, across the Strait of Messina, where ferries ply between Scylla and Charybdis, northwards past Calabrias citrus orchards and olive groves and beyond Naples, the city to see and die. But this is also the story of dedicated magistrates and policemen who struggle against the odds to enforce the law and see justice done in parts of Italy where law and justice are often private matters. It is the story of young people who form cooperatives to work land confiscated from the Mafia and ordinary Italians who want the Mafia beaten. It is the story of a journey through the Mezzogiorno, of discovering its contrasts and contradictions, from the ruins of Magna Grcia and Baroque palaces to the relics of doomed industrial ventures and ugly developments along the coast. And it is the story of the good and the evil in the South.

My Italian travels began in the spring of 1972 when I moved to Rome on a six-month assignment at the Cassa per il Mezzogiorno, the development agency for the South, and stayed for ever. Perhaps there was a reason that a young foreigner, an ingenuous newcomer to the seductive Bel Paese, as Italians often call their country, was allowed to read the files of hundreds of engineering projects that took electricity and water to towns and villages, and joined them with roads and railways. Caught up in discovering the tourists Italy and exploring Rome, the Eternal City, I was incurious about the firms involved and the powerful politicians who wrote to the agency supporting projects or soliciting payments to those firms.

When my interests shifted, I would see roads leading from nowhere to nowhere else, a huge viaduct built in fields and half-completed hospitals where construction had halted long ago, and learn that the Mafia had a hand in public works throughout the South. Indeed, for me, my full sighting of the Mafia only came many years later, although I wonder now if I did not brush against it much sooner, and get closer than I did in the Cassas drab offices in Rome.

Few of the tables, set with white linen and tasteful chinaware, were taken at around eight thirty on that morning early in 1978. The restaurant was quiet, an occasional clink of cup on saucer and rustle of newspaper pages being turned. It was not a week when models strutted along Milans catwalks, drawing crowds of buyers, journalists, gawkers and other fashion-followers. Unhurried, waiters lavished attention on a smartly-dressed businessman sitting on the other side of the room. A regular guest perhaps, but how the waiters served him said that he was somebody who counted more than most.

Like Rome six years before, Milan was a city to be discovered, its museums and churches to be visited, its hotels to be experienced. Since then I have stayed at around thirty different places in the Lombard capital: luxury hotels and modest ones, five-star and two-star, the smart and the scruffy, some in the financial district, others near the old trade fair and San Siro, and a small hotel, which for some reason Italians describe as meubl, in the fashionable heart of Italys fashion capital. Yet after staying occasionally between the beginning of 1978 and summer of the following year, I have never returned to the Hotel Splendido where the enigmatic man also stayed.

At number four Viale Andrea Doria, the Splendido is a hundred yards from Milans central station, one of dozens of anonymous hotels that pack whole streets in that dismal district of transients, but one of the smartest, boasting four stars and the Rendez-Vous, a restaurant that the Touring Club Italiano nowadays calls elegant. I was eating breakfast there that morning because of an appointment with a client. The consultancy firm for whom I worked had an assignment with a company whose offices were about ten minutes walk from the hotel. The companys owner used the Splendido, was the person I had to meet and, as I would soon learn, was the man at the table on the far side of the restaurant whom the waiters treated with such respect.

Twenty-five years later I came across the hotel again, towards the end of a book the story of the work and death of Giorgio Ambrosoli, the Milanese lawyer responsible for liquidating the Banca Privata Italiana, a bank owned by Michele Sindona, a Sicilian financier. Hotel Splendido: the name sprang from the page.

Using a false American passport bearing the name Robert McGovern, William Arico had arrived at Milans Malpensa inter-continental airport on the morning of 8 July 1979 and, after renting a car, had driven to his usual hotel. This was his tenth visit to Milan and the Hotel Splendido since September of the previous year and those visits had often coincided with threats against Ambrosoli or other acts of intimidation. And that visit would be Aricos last. Almost certainly when he stayed there during the second half of June, Arico had used his time to decide where and how he would murder Ambrosoli. He returned in July to do the job. Just before midnight on 11 July Arico, a hit man hired by Sindona, murdered Ambrosoli as he returned home after dinner with friends. On the following day the lawyer had been due to give evidence in the Milan court to American prosecutors who, pursuing their case against Sindona, had also arrived in the city on 8 July.

Next page