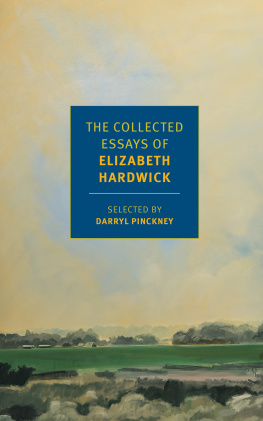

Darryl Pinckney - Busted in New York and Other Essays

Here you can read online Darryl Pinckney - Busted in New York and Other Essays full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2019, publisher: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Busted in New York and Other Essays

- Author:

- Publisher:Farrar, Straus and Giroux

- Genre:

- Year:2019

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Busted in New York and Other Essays: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Busted in New York and Other Essays" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Busted in New York and Other Essays — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Busted in New York and Other Essays" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

For Priscilla Roth

Every existence has its idiom.

Whitman

Each summer, in London, I speak to a group of teens participating in Target Oxbridge, a program that encourages black students to apply to university. They ask me about my college experience and wonder what their own might be. One persistent anxiety trumps all: Will this make me less black? From here, the conversation expands into existential territory, as they describe the many behaviors and traits they fear will place their blacknessin the eyes of othersin jeopardy. Things like reading or writing too much, wearing certain clothes, speaking a particular way, having been to private school, living in the countryside. Sometimes I ask them to imagine a group of white students sitting there in our stead. What dangers could we conjure up that might put their whiteness in jeopardy? But we can only ever think of oneextreme povertyand even then, it would likely not be their existential whiteness theyd consider endangered but only the privileges that may have once attended it. The imagined white students vanish. We sit together in our blackness and wonder: Can blackness really be so fragile an edifice that even a pair of narrow jeans may threaten it?

In Darryl Pinckneys life and work blackness is not so easily revoked. In his essays, blackness is as much in a black mans possession at a British pro-fox-hunting demonstration as it is at the Million Man Marchor while reporting on the protests in Ferguson, Missouri. He will retain it while writing operas in Berlin or falling in love (with a white, male poet) in Paris or reading Nancy Mitford. His blackness remains his even as he ponders the historical fact (alongside James Baldwin and Ta-Nehisi Coates) that race is, in the final analysis, a social and political construction:

In his writings, Baldwin stressed that the Negro problem, like whiteness, existed mostly in white minds, and in Between the World and Me (2015), Coates wants his son, to whom he addresses himself, to know this, that white people are a modern invention. Race is the child of racism, not the father.

As a piece of rhetoric this has become increasingly easy to assert, and many say it, but it is Pinckneys habit always to dig behind rhetoric to the historical record, where things are somewhat more difficult to say but no less true; for example, that blackness, too, must therefore be an equally modern invention, for white and black as categories are coeval, the creation of the first necessitating the other:

Colonial law quickly made a distinction between indentured servants and slaves and in so doing invented whiteness in America. It may have been possible for a free African or mixed-race person to own slaves, but it was not possible for a European to be taken into slavery. The distinction helped keep blacks and poor whites from seeking common cause.

Pinckneys emphasis on the interpolation of class and race can make him appear closer to the leftist Afro-Caribbean tradition of race theoristsexemplified by thinkers like Paul Gilroy and Stuart Hallwho reject mythical or essentialist theories of racism (from the Curse of Ham to an inexplicable primordial hatred and horror of black bodies) in favor of a concrete economic analysis, in which racial distinctions have been created and maintained primarily for the sake of capitalist exploitation. For Pinckney, blackness is not an essential quality found in the blood, the spirit, or even the genes (Ive never liked that way of assigning to whole nations or groups innate behavioral characteristics. The work of every serious social scientist militated against it) but a conceptual framework subject to history, like everything else: People were Jewish or Welsh before they were white. The Irish used to be black socially, meaning at the bottom. The gift of being white helped subdue class antagonism.

Of course, just because something is constructed, it does not follow that it isnt meaningful. As Coates himself puts it with poetic succinctness: They made us into a race. We made ourselves into a people. And it is to the history of this people that Darryl Pinckney attends. The legislation to which we have been subject; the economic and social exclusion we have suffered; the experiences, both personal and public, that we have shared; our joys, our pains. But because he has a truly encyclopedic knowledge of black historystretching far beyond America to every corner of the globethe question of who and what this we contains remains at the forefront of Pinckneys inquiry. What exactly do we share? How do we diverge? From the concluding lines of his essay on Coates, The Afro-Pessimist Temptation: Black life is about the group this remains a fundamental paradox in the organization of everyday life for a black person. Reading these lines, I thought of those students in London, never quite sure as to how or where they should draw the Venn diagram between the selves they feel so strongly and the we to which they no less profoundly belong. Can a diaspora be a monolith? Should it be?

In Slouching Toward Washington, Pinckneys account of attending the 1995 Million Man March, this question is no thought experiment but a pressing problem: Everyone seemed in a prescriptive frame of mind, willing to go on record about what black men and therefore black people needed to do.

As anyone who has been on a march knows, you find yourself on such occasions shoulder to shoulder with ideological brothers, cousins, and strangers, and as moved as Pinckney is by the huge crowd, by the solemn courtesy each man shows the other as they move through the throngExcuse me, brother Excuse me, black mannot every speech he heard that day spoke to him, and not every voice lifted was the song he wanted to sing. He hears a troubling capitulation in the exhortations that black men accept responsibility for their families (he hears the same capitulation thirteen years later when Obama makes a similar cri de coeur) and wonders why all the men on the Mall that day should have to swear as black men not to beat their wives, promise as black men not to abuse their children as if domestic violence and poverty were not also white problems. Pinckney is the inconvenient scholar who knows, when Louis Farrakhan stands up and purports to quote a letter of 1612, written by one Willie Lynch, slave master, that this letter is a fraud, written in language that in no way belongs to the early seventeenth centuryand yet there is nothing vituperative in his style, and hes never out for anybodys blood. (No doubt [Farrakhan] assumed that everyone understood the letter was apocryphal, a parable about fear, envy, and distrust, the means by which blacks are kept disunited.) Still, the truth matters. An invented past can never be used, argued Baldwin, and Pinckneys historical precision reminds us that there is more than sufficient systemic oppression in the black past and the black present not to require any added fictionalization. Instead of Farrakhans murky conspiracy of whites against blacks, we might consider that in the first quarter of the nineteenth century Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, North and South Carolina, and Virginia passed anti-literacy laws, some of which included prison time for anyone who taught a slave to read and write, while as Farrakhan speechified, there existed a perfectly nonfictional, racially biased criminal justice system that destroyed the lives of far more than a million black men.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Busted in New York and Other Essays»

Look at similar books to Busted in New York and Other Essays. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Busted in New York and Other Essays and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.