Chapter Five

In the Interest of the Indians, 191516

By the close of 1914, the 125,000 old contemptibles of the bef had suffered 90,000 casualties. Although the dominions mobilized expeditionary forces and conducted training both at home and abroad, no dominion forces participated in major campaigns during 1914. During 1915 and 1916, however, those forces expanded and became key components of the fighting strength of the bef on the Western Front and at Gallipoli. High casualty rates accompanied this participation, and the swelling expeditionary forces required increasing reinforcements to sustain their national formations. The increasing overall strength of Allied armies was accompanied by the immediate need for service and support auxiliaries, such as labour battalions, forestry corps, and pioneer battalions. Britain increasingly looked to her dominions as a source of men and materials. Amplified dominion participation, however, was accompanied by greater demands for inclusion in strategic and operational counsel by dominion prime ministers, most notably by Borden, to satisfy nascent domestic national consciousness.

Within this general atmosphere, in October 1915 the British War Office issued the most important imperial documents of the war pertaining to indigenes of all dominions. Official inclusion of Indians in the cef and the clarification of policy in December 1915 were directly linked to the requests of the imperial government. While Canadian scholars have noted the drastic shift in policy towards greater Indian inclusion after October 1915, not one has referenced these documents, nor made any connection to the demands of the senior British government. On 8 October 1915 all governors general and administrators of British dominions and colonies received a confidential memorandum from the Canadian-born colonial secretary, Andrew Bonar Law: In the British interpretation, the loyal service of Indians during the colonial period still resonated and was again requested in aid of the empire.

The 1st Canadian Division arrived in France on 16 February 1915. On 3 March battalions entered the lines at Fleurbaix and took part sparingly in the Battle of Neuve Chapelle (1013 March 1915). The 1st Division suffered 320 casualties in March, in what was labelled a familiarization period. During its tour in the Ypres Salient, between 15 April and 3 May, the division suffered 6,104 casualties out of roughly 16,500 engaged (37 percent)the majority between 22 and 25 April. During these four days, although the number of Indians present in the division was small, eight became casualties, including five killed.

Compounding the need for manpower in the face of these casualties was the drastic expansion of the cef in 1915. The 2nd Division, authorized on 9 October 1914, joined the 1st Division in France in September 1915, facilitating the creation of the Canadian Corps. On 30 October Borden increased the authorized strength of the cef to 250,000, despite sober counsel from Gwatkin that there is a limit to our production. You cannot put every available man into the firing line at once. Casualties must be replaced. It takes 3,000 to place 1,000 infantrymen in the field and to maintain them there in numbers and efficiency for a year. Nevertheless, a 3rd Division was formed from surplus reserves in France on 24 December 1915. On 31 December Borden doubled the authorized strength of the cef to 500,000, an increase that was accompanied by this threat to the British government:

It can hardly be expected that we shall put 400,000 to 500,000 men in the field and willingly accept the position of having no more voice and receiving no more consideration than if we were toy automata. Any person cherishing such an expectation harbours unfortunate and even dangerous delusion. Is this war being waged by the United Kingdom alone or is it a war waged by the whole Empire?... Procrastination, indecision, inertia, doubt, hesitation and many other undesirable qualities have made themselves entirely too conspicuous in this war. Another very able Cabinet Minster spoke of the shortage of guns, rifles, munitions, etc., but declared that the chief shortage was of brains.

Since the beginning of October, Borden had been relentless in demanding greater involvement in the direction of the war. According to Borden, nationalist considerations could not be ignored if recruitment was to be sustained, as the Governments of Overseas Dominions have large responsibilities to their people for conduct of war and we deem ourselves entitled to fuller information and to consultation respecting general policy in war operations.

In late 1916 Borden craftily enhanced Canadas position within the political spheres of London. In November, he forced the resignation of the minister of militia, Sam Hughes, explaining, his conduct and speech were so eccentric as to justify the conclusion that his mind was unbalanced.

In reality, Bordens commitment of 500,000 men, in light of casualty rates, would require the immediate enlistment of 250,000, and an additional 25,000 men per month (300,000 annually) if its strength was to be sustained. Senator James Mason reported to his colleagues that these figures will not be obtained under the present system of enlistment. To meet Bordens imperious and idealistic promises, Canada needed to significantly bolster recruitment.

ILLUS. 7. The 1,000 Yard Stare: Canadians Returning from the Somme Front, November 1916. Library and Archives Canada, PA-000832.

To meet the demand for manpower in November 1915, the government authorized prominent individuals and communities to recruit and raise battalions for overseas service outside of official military circles, with the consent of the Ministry of Militia, which did not forego financial responsibility. Throughout 1915 confusion prevailed as to the legality of enlisting Indians, and scores of requests were submitted to the Ministry of Militia and the dia . For example, in October 1915 Cape Croker Chippewa Indian agent A.J. Duncan questioned Indian Affairs as to why three men from his reserve were denied enlistment at four different stations while other Indians had been accepted.

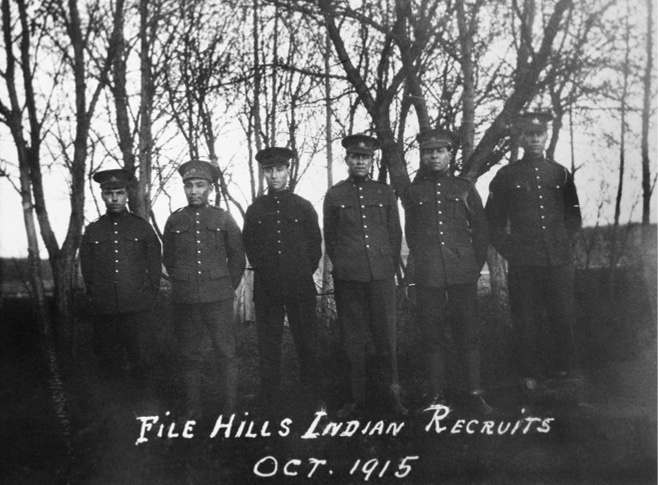

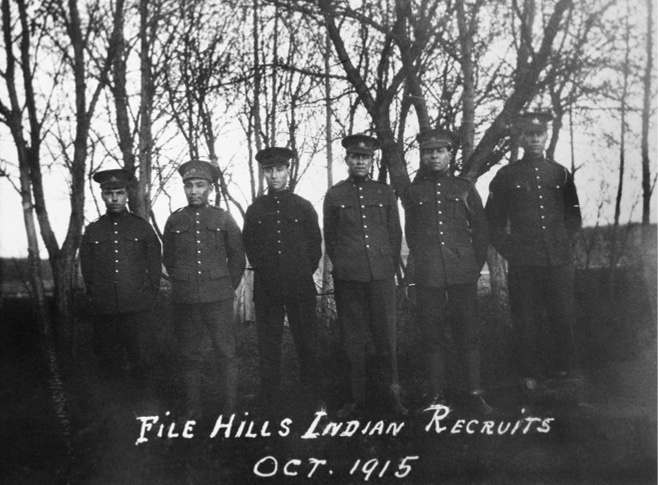

ILLUS. 8. Cree Recruits from File Hills, Saskatchewan, October 1915. Left to Right: David Bird; Joe McKay; Leonard McKay; Leonard Creely; Jack Walker; Harry Stonefield. Glenbow Museum Archives, NA-3454-41.

On the Six Nations reserve, Merritt continued to press for the formation of Indian companies and acquired the assistance of Six Nationsborn Mohawk Frederick O. Loft, a militia veteran of seven years and an accountant at the Toronto-based Provincial Lunatic Asylum. Loft addressed the council and warriors who were present in large numbers on 24 March 1915. The council, after touching on the various relations existing between the Chiefs of the Six Nations and the British Crown, offered their decision. According to the council minutes, The chiefs did not deem it proper that they should ask the government to allow them to form companies when they already have the 37th Battalion on the reserve and are standing ready to respond when called to do so by the [British] Department of War.

Nevertheless, in November F.R. Lalor, mp for Dunnville, Ontario, and Lieutenant Colonel Edwy Sutherland Baxter, 37th Haldimand Rifles commanding officer, appealed to Sam Hughes to raise a battalion in the Dunnville-Caledonia-Six Nations area. Although it was to include Indians, it was not initially intended to be solely an Indian unit. Baxter was known to the Six Nations and was one of the most popular men in the opinion of the Indians, according to a December 1915 article from the local Brantford Expositor . While the Ministry of Militia approved the battalion, no mention was made concerning Indians, as recruitment remained within the discretion of local commanders, in this case Baxter. He believed that he could muster 200 to 250 Indians from the Six Nations reserve, given that many of these men were already active in his militia unit.

Next page