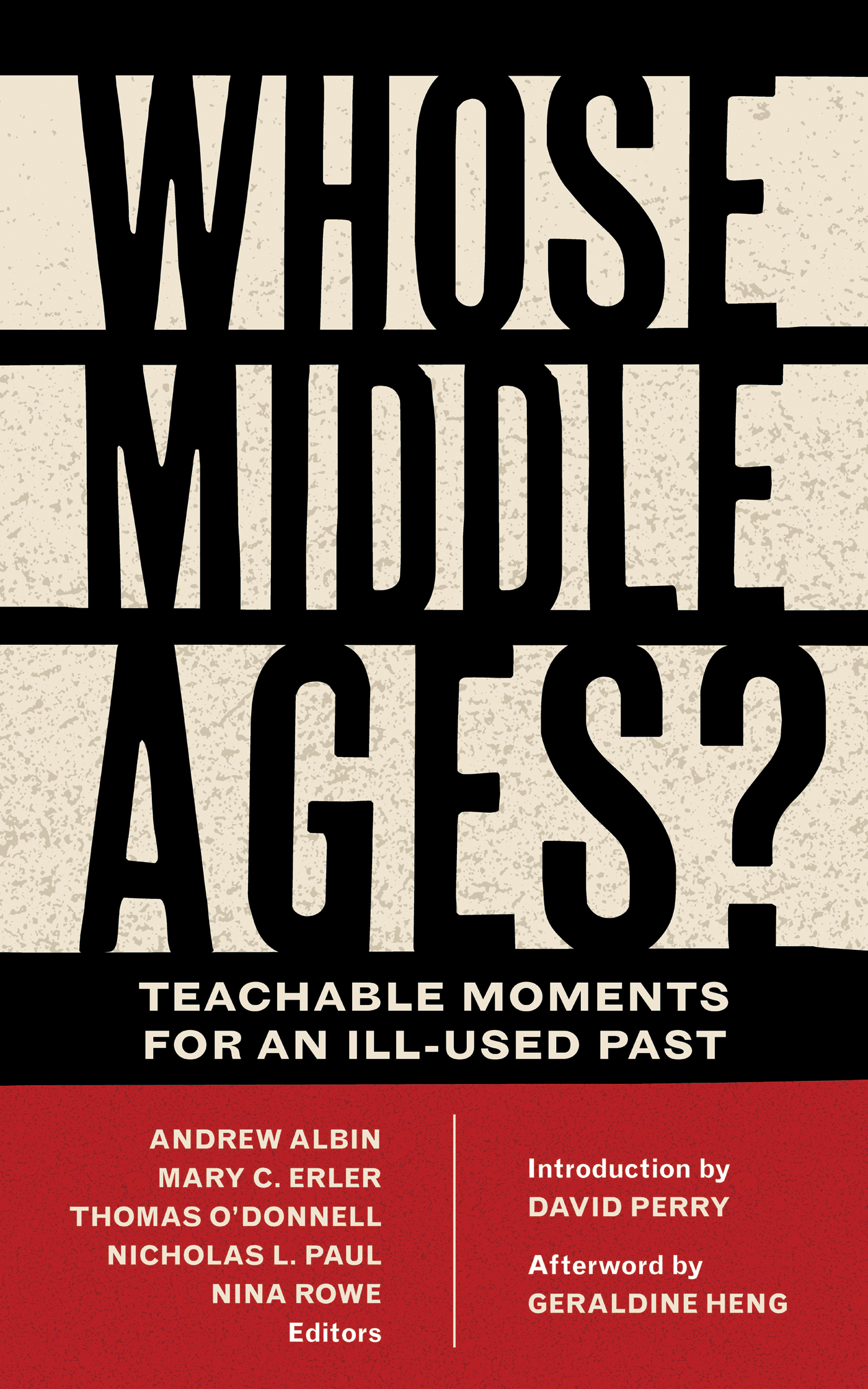

WHOSE MIDDLE AGES?

| Whose Middle Ages? TEACHABLE MOMENTS FOR AN ILL-USED PAST |

Andrew Albin

Mary C. Erler

Thomas ODonnell

Nicholas L. Paul

Nina Rowe

EDITORS

INTRODUCTION BY DAVID PERRY

AFTERWORD BY GERALDINE HENG

FORDHAM UNIVERSITY PRESSNEW YORK 2019

Fordham Series in Medieval Studies

Copyright 2019 Fordham University Press

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any meanselectronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any otherexcept for brief quotations in printed reviews, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Fordham University Press has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of URLs for external or third-party Internet websites referred to in this publication and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate.

Fordham University Press also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books.

Visit us online at www.fordhampress.com.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available online at https://catalog.loc.gov.

Printed in the United States of America

21 20 195 4 3 2 1

First edition

Contents

David Perry

Sandy Bardsley

Katherine Anne Wilson

Nicholas L. Paul

Magda Teter

Fred M. Donner

W. Mark Ormrod

Cord J. Whitaker

Ryan Szpiech

William J. Diebold

Lauren Mancia

Stephennie Mulder

Sarah M. Gurin

Pamela A. Patton

Elizabeth M. Tyler

David A. Wacks

Marian Bleeke

Andrew Reeves

Maggie M. Williams

Helen Young

Will Cerbone

Adam M. Bishop

J. Patrick Hornbeck II

Geraldine Heng

WHOSE MIDDLE AGES?

Theres no such thing as the Middle Ages and there never was. The notion of a medium aevum that is neither one thing nor the other, permanently stagnating in the in-between, has always been a fiction. This isnt unusual. All eras are fictions. We humans love to apply our retrospective gaze on the sweeping vistas of the past, then chop them up into neat little periods to help us make sense of time. We allow periods to take shape in our cultural imagination when they serve a purpose, when we use them to define a present against its various pasts, whether through assertions of affinity or otherness. Theres nothing necessarily wrong with these handy fictions about time, at least not until we allow the convenient shorthand to morph into something we mistake as objectively real. Heres the truth, at least for the way that most of us talk about truth: There never was any such thing as the Middle Ages.

And yet the Middle Ages undeniably exist. Theyve been roaring through cultural imaginations more or less constantly over the last five or six centuries. They started as a collection of years and peoples from whom thinkers in the Italian Renaissance wanted to distance themselves. In eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Western Europe, the imagined medieval occupied a more cherished space, a period of purity in comparison to perceptions of racial and cultural mixing that threatened Europeans ideas about their superiority. Today, well, today things are as complicated as ever. But studying both the Middle Ages and how people have thought about and tried sometimes to appropriate them can pay enormous dividends for the understanding of both history and the present day. Scholars of this period not only get the pleasure of engaging with complex source material, sometimes even handling the raw stuff of the past themselves, but acquire technical and theoretical skills and habits of mind with broad applications.

For evidence, flip through the essays in this volume. In each case, consider the tools that these scholars of the Middle Ages and medievalism (the deliberate adoption, reinvention, and implementation of tropes the creator imagines to be medieval) leverage in order to make their case and explore these questions of ownership and identity linked to modern exploitation of the medieval past.

Heres just one gem from this collection that we might pull out into the light and examine, the essay of Stephennie Mulder, No, People in the Middle East Havent Been Fighting Since the Beginning of Time. Mulder examines the narratives that identify the seventh-century ShiaSunni schism as the source of modern conflict in the region. Historians have chosen to support the modern story of ancient origins and constant conflict through analysis of the extant primary written record. But Mulder is an art historian and leverages the history of the buildings she studies to complicate a simple narrative of conflict. She tells us that during this era of supposedly unending violence, Shia shrines were endowed, patronized, and visited by both Sunnis and Shiis: in many cases, by some of Islams most illustrious Sunni rulers. A technical expertise in the history of buildings attained through careful study of the remaining structures and more quotidian sourcesabout the funding and attendance of those structureswould enable us to reimagine our whole history of the politics of the Middle East.

The other essays in this volume offer similar gifts through a wide variety of tools. Helen Young explains why even people who arent avowed white supremacists get uneasy when people of color appear in medieval fantasy settings (even though there were people of color, in fact, living in medieval Europe). Her tool isnt a technical expertise, but rather an engagement with critical race theorya body of knowledge and methodological approach that instructs us to examine the power structures of societies as vehicles for maintaining racial hierarchies. Cord Whitakers essay also relies on careful deployment of literary and cultural theory, but here he does something different. He applies his skill as a reader of medieval texts to works of medievalism that lie withinperhaps, he says, at the very heart ofthe Harlem Renaissance. We cannot understand this flowering of black culture, Whitaker argues, without critical engagement with both medievalism and the Middle Ages. Medievalism in the nineteenth century is always linked with amateurism and fraudthe inventors of Scottish clan tartans, the founder of the semi-Masonic orders of the Knights Templar (unrelated to the crusading order), and so forth. Amateurish revival work could also provide a valuable bedrock for nationalism as the various European nations sought specific narratives of the past to unite diverse factions under the banner of the nation-state. Whitaker, however, places a romantic love of medieval texts and images within a transformative cultural moment in a marginalized population.

Over the last few hundred years, there were two dominant ways of putting notions about a middle age to use. Italian Renaissance thinkers who sought to craft a connection between themselves and the thinkers of classical Greece and Rome deployed a medievalism that distanced themselves from the more recent past. The Renaissance, itself a useful fiction, took place during a period of exceptional turbulence in politics, culture, and economics, yet also featured innovative intellectual and artistic practices that sought inspiration in the classical world. Hence, Renaissance artists and thinkers proposed that they had left behind a middle age between the cultural greatness of Rome and the greatness to which they aspired in their own time. In fact, historians can trace just as much continuity with the preceding medieval centuries as they can identify innovation during the Renaissance. Moreover, many of the features we most identify as belonging to the Renaissance found their origins not in ancient Rome but in the medieval Islamic world or even further afield.

Next page