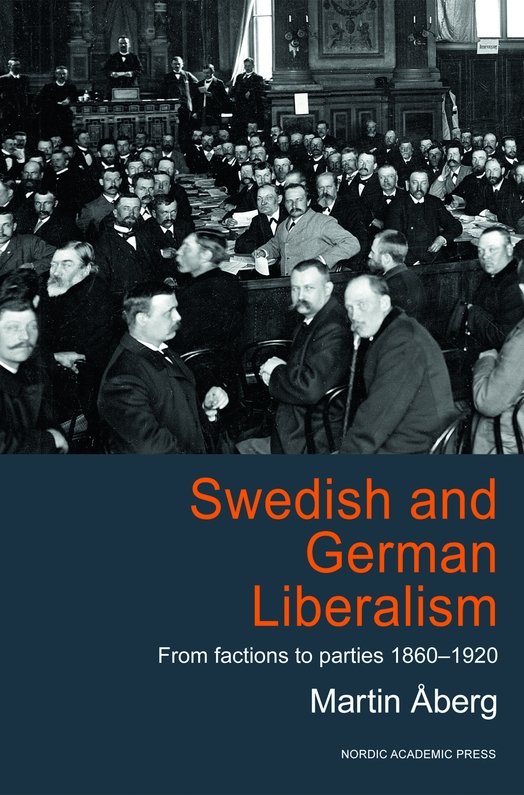

Åberg - Swedish and German Liberalism : From Factions to Parties 1860-1920.

Here you can read online Åberg - Swedish and German Liberalism : From Factions to Parties 1860-1920. full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2015, publisher: Nordic Academic Press, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

Swedish and German Liberalism : From Factions to Parties 1860-1920.: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Swedish and German Liberalism : From Factions to Parties 1860-1920." wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Åberg: author's other books

Who wrote Swedish and German Liberalism : From Factions to Parties 1860-1920.? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Swedish and German Liberalism : From Factions to Parties 1860-1920. — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Swedish and German Liberalism : From Factions to Parties 1860-1920." online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Det sger sig sjlft, att de nu freslagna jmkningarna i metoden ingalunda kunna frebygga sdana oegentligheter, som hafva sin grund vare sig i obekant-skap med valmetoden eller i illojala valmanvrer. Srskildt gller detta den ngra gnger frskta kuppen att illojalt anvnda ett annat partis partibeteckning. Skulle den frihet, som den nuvarande valmetoden i detta hnseende lmnar, fortfarande missbrukas, och den politiska moralen icke tillrckligt reagera mot dylika tilltag, s terstr intet annat n att infra den offentliga kandidaturen med officiellt faststllda vallistor. Albert Petersson, Om ndringar i lagen om val till Riksdagen med flera frfattningar, no. 5, 10. Motioner vckta inom andra kammaren, 1190. Bihang till riksdagens protokoll 1912 . The motion was brought in protest against the liberals and the social democrats, who had formed cartels under joint party labels in 15 constituencies during the election campaign. SOS. Allmnna val. Riksdagsmannavalen ren 19091911 , 40.

191821, because constitutional reforms of this kind required confirmation by two consecutive parliaments. Womens right to vote was introduced parallel with democratization of the municipalities.

To make his point, Duverger referred to Humes Essay on Parties. The English, 1954, edition of Duverger reads: In his Essay on Parties (1760) David Hume made the shrewd observation that the programme plays an essential part in the initial phase, when it serves to bring together scattered individuals, but later on organization comes to the fore, the platform becoming subordinate. Nothing could be truer. More specifically, Hume published three essays on parties. These were Of Parties in General [1741], Of the Parties of Great Britain [1742], and Of the Coalition of Parties [1760]. The closest match between Hume and Duverger in this respect is to be found in the 1741 essay, where Hume notes that Nothing is more usual than to see parties, which have begun upon a real difference, continue even after that difference is lost. When men are once inlisted on opposite sides, they contract an affection to the persons with whom they are united, and animosity against their antagonists; and these passions they often transmit to their posterity, Hume 1904 [1741], 5657; Hume 1964 [1882], 129. This, however, has little to do with the organizational framework of parties.

Matters of translation, spelling and placenames are never easy to resolve when the topic involves more than one linguistic and historical setting. HereSwedish and German quotes have been translated into English, but with the original text given in the notes. I have used the standard English place names, but otherwise Swedish and German names; hence for instance Bavaria rather than Bayern and Gothenburg rather than Gteborg, but Vrmland, Schleswig-Holstein, Flensburg, Karlstad and so on.

The debate most notably on German liberalism, and on the issue of how and when liberal ideology changed in nature has been extensive. In later research, Eley 1980, and Blackbourn 1980, for instance, have stressed the 1890s as the crucial period, in addition to which they, like Langewiesche 2000 [1988], also provide a more nuanced picture of German liberalism. See more recently Palmowski 1999, and Gross 2004, for extensive historiographical reviews. By comparison, Swedish research on liberalism is far less extensive. Hurd 2000 and Nilson & berg 2010, are among the most recent contributions.

It should be pointed out that, like Sweden, Denmark and Norway may also be used as examples of rural liberalism; see Thomas 1988. According to the rationale of the present study, however, Germany, rather than Denmark or Norway, is to be preferred for the purpose of comparison.

The approach therefore rests on a most different systems design (MDSD); see for instance Przeworski & Teune 1970, and Denk 2002. However, I refrain from using this terminology mainly for two reasons. Firstly, my point of departure is not contingent on one particular theory of parties or party system formation. Secondly, considering the historical context, data does not allow systematic, let alone quantitative, testing of hypotheses in a manner consistent with MDSD models.

Archive material pertaining to liberal organization on the regional level is, with certain exceptions, usually scarce. (This might, indeed, be indicative of liberal attitudes towards formal organization.) Although regional-level party material exists in the public archives in the case of Vrmland this is not the case for Schleswig-Holstein. Political activities and elections in Germany were, however, more closely monitored by the government compared to Sweden, and the official records kept, for instance in connection to the election campaigns, provide valuable information which to some extent makes up for the lack of party records. In both countries newspapers are also rich in information on political association and elections.

The Swedish Social Democratic Party did however display a more decentralized pattern from the outset (the party was founded in 1889) similar to Austria. Soon enough, however, the party moved closer to the German model, and it began to adopt a more centralized structure in the 1890s. The final stages of this transition, though, were not completed until the inter-war period (Gidlund 1989, Schllerqvist 1992).

Gustaf Albert Petersson in my introductory example was minister of justice inthe conservative cabinet of Admiral Arvid Lindman, 190611, and member of parliament 191217. See also the Introduction, endnotes, on the background to his complaints.

Protokoll, 29 July 1917, 7. Norra Vrmlands frisinnade valkretsfrbund, Protokoll, 1, 190922. Folkrrelsernas arkiv fr Vrmland. Arkivcentrum Karlstad.

The essay in question is Of Parties in General [1742], originally published in the second volume of Humes essays. On the topic of Whigs and Tories, however, Hume believed that the formation of British parties was an inescapable part of political life, considering the specificities of British constitutional development. See 1904 [174142], Of the Parties of Great Britain.

Kieler Zeitung , 10 February 1871.

Other relevant concepts, such as Gemeinschaft and Gesellschaft (see chapter 2) were also, and still are, extremely difficult to transfer between different historical, ideological, and linguistic settings. We may simply consider the manner in which the translations into English of Ferdinand Tnnies concepts differ across time. For instance, the 1955 Routledge & Keegan Paul edition of Gemeinschaft und Gesellschaft is titled Community and Association , whereas the 2001 Cambridge University Press edition is titled Community and Civil Society . Other editions have the title Community and Society .

I am aware that this is not in line with common conceptions of civil society, such as in Keanes, analysis (1988). Historically speaking, however, civil and political association were often considered to be closely connected. Then again, the problem is not easily resolved. It is, among other things, contingent on how we define the state and politics; also it could be said about civil and political associations that they operate in the interface between society, or the individual, and the state. See also Trgrdh 1999.

Staaffs principles on the matter were laid down in his posthumously published, comparative study of democracy as political system (Staaff 1917, I, 37073).

Protokoll, 2 April 1934, 11. Vrmlands frisinnade valkretsfrbund, Protokoll, A I:1, 192234. Folkrrelsernas arkiv fr Vrmland. Arkivcentrum Karlstad.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Swedish and German Liberalism : From Factions to Parties 1860-1920.»

Look at similar books to Swedish and German Liberalism : From Factions to Parties 1860-1920.. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Swedish and German Liberalism : From Factions to Parties 1860-1920. and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.