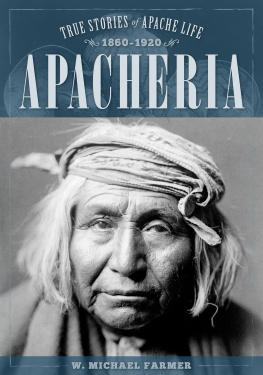

Apacheria

True Stories of Apache Culture 18601920

W. Michael Farmer

An imprint of Globe Pequot

A registered trademark of Rowman & Littlefield

Distributed by NATIONAL BOOK NETWORK

Copyright 2017 W. Michael Farmer

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Farmer, W. Michael, author.

Title: Apacheria : true stories of Apache life, 18601920 / W. Michael Farmer.

Description: Guilford, Connecticut : TwoDot, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017046578 (print) | LCCN 2017047245 (ebook) | ISBN 9781493032808 (e-book) | ISBN 9781493032792 (pbk. : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Apache IndiansHistoryJuvenile literature. | Apache IndiansSocial life and customsJuvenile literature.

Classification: LCC E99.A6 (ebook) | LCC E99.A6 F37 2017 (print) | DDC 979.004/9725dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017046578

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

Printed in the United States of America

For Corky, my best friend and wife

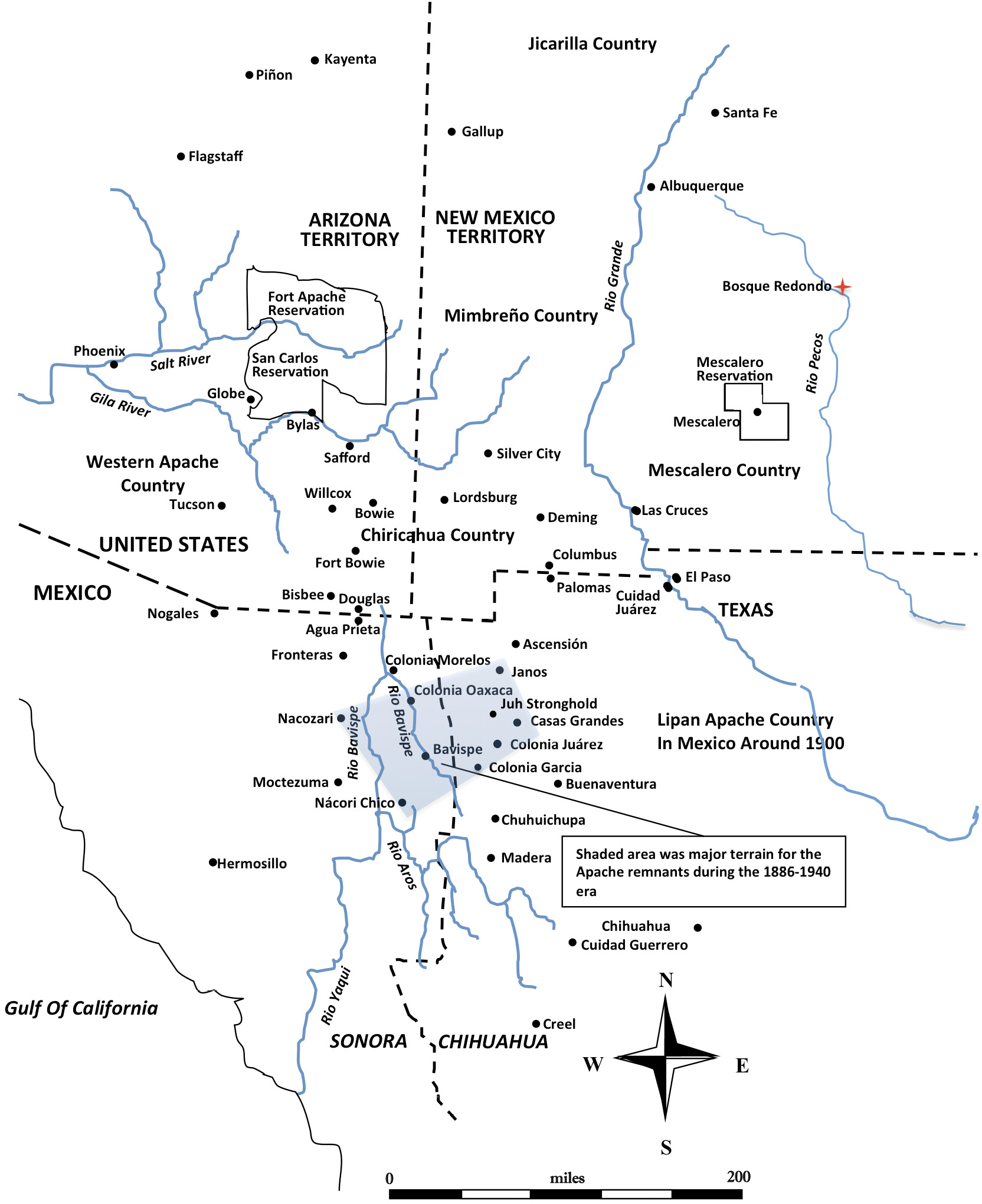

The Apacheria Prior to 1886. (Towns built after 1886 are shown for points of reference.)

Michael Farmer

Acknowledgments

There have been many contributors to this effort. A few deserve special mention. Erin Turner, editor at Two Dot, chose to make this book possible and has been very supportive and helpful throughout its development.

Melissa Star helped edit the text, providing an additional pair of eyes for finding errors and inconsistencies, and has been a major contributor to the quality of the work.

Lynda Snchez shared rare photographs from her collection developed over years of research with Eve Ball and helped keep me grounded in the historical realities of the Apache People.

Ms. Teddie Moreno, Library Specialist for Archives and Special Collections, has provided great support in providing me photographs I requested from the New Mexico State University Rio Grande Collection of photographs. Ms. Coi E. Drummond-Gehrig, Digital Image Collection Administrator for the Denver Public Library, was very helpful in acquiring the image for Lieutenant Stottler and the Jicarilla family. Tom Schmidt, Reference Desk Coordinator for the Sharlot Hall Museum Library and Archives in Prescott, Arizona, helped provide a hard-to-find image of the Apache Kid and other prisoners at the 1889 Globe Trial.

I would be remiss not to express to the many readers of the original drafts of these essays my sincere appreciation for their support and comments.

Finally, to my wife, Carolyn, I owe much for her encouragement and support without which this work would not have been possible, and it is to her that this book is dedicated.

Preface

The history of the Apaches in the last half of the nineteenth century and the early years of the twentieth century is filled with stories of strength, cunning, courage, and tragedy. The Apaches, if equally armed, were often far better warriors in the land of their fathers than their white counterparts, who faced tough, implacable enemies in a great, unknown wilderness. However, what the Anglos lacked in knowledge of the land and fighting skills, they more than made up for with nerves of steel, unending numbers, virtually unlimited supplies, and a belief that their social mores and Christian religious beliefs were clearly superior to those of the Apaches. The Anglos courage, numbers, and supplies forced the Apaches on to small bits of land called reservations, which by treaty were to be protected with the same rights as foreign countries within the United States. The Anglos didnt keep their agreements, took back much of the reservation land, and even attempted to change Apache lifeways to more nearly match those of Anglo society. As a result, the battle moved from a fight for land to one for souls, and it continues to this day.

This book draws on the work of respected historians and ethnologists and visual imagery from the times to provide the general reader a collection of true stories with associated visual images of the life and times of the Apaches from about 1860 to 1920, a period of brutal wars with Mexicans and Anglos, internment on reservations (some often virtual prisoner of war camps), and government-directed attacks on their lifeways. My intent with these stories is to give the reader a three-dimensional historical perspective that is possible only by telling of events, times, and persons seen through a white eye and through an Apache eye to eliminate the historical parallax that develops when only one point of view is given. These stories show the Apaches were no more savage than the Mexicans or Anglos, who ultimately forced them to surrender their wild and free ways, and the stories help to focus additional light on an epic saga in American history far too long in the shadows. The Apaches, taught to endure hardship and suffering from the time they were off their cradleboards, and to make war with no quarter given or expected in a hard, unforgiving land, have survived the years of hardships imposed by an often ignorant and uncaring government and made their way to stand tall and proud as survivors who leapt from the Stone Age to the Atomic Age in a generation. The facts of the stories salute their courage and strength.

Only a few of the stories that fill this great, uniquely American saga can be presented here. While these stories are by necessity brief, the interested reader can find additional information and details in the notes and additional reading list of trusted historical and cultural work that follow.

W. Michael Farmer

Smithfield, Virginia

September 2017

Introduction

Geronimos surrender to the U.S. Army on September 4, 1886, brought to an end more than 25 years of sustained conflict between the Apaches and Americans and 250 years of conflict with Spaniards and Mexicans. For forty years after the surrender of Geronimo, most Anglos and Mexicans knew little or nothing about the actual lifeways of the Apaches or their wars. Information for the histories that were written during that time came, for the most part, from military records, reservation agent reports, and newspapers. And Apaches were almost invariably portrayed in popular accounts as howling demons murdering, scalping, raping, torturing, and burning anyone or anything that stood in their way. They were consummate villains, and the public was fascinated.

Nearly twenty years after he surrendered, Geronimo, the best-known Apache villain, rode his horse (along with five other well-known chiefs from the Indian wars) in Theodore Roosevelts 1905 inaugural parade. Next to the president, he was the second-most popular man in the parade. In the years since his surrender, he had become a celebrity, appearing in parades and expositions all over the United States as an Apache patriot. As he rode down Pennsylvania Avenue, men threw their hats in the air and yelled, Hooray for Geronimo! He was, in the disgusted words of Woodworth Clum, son of the famous San Carlos Indian agent John Clum, who was the only man actually to capture Geronimo, Public Hero Number Two.

Next page

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.