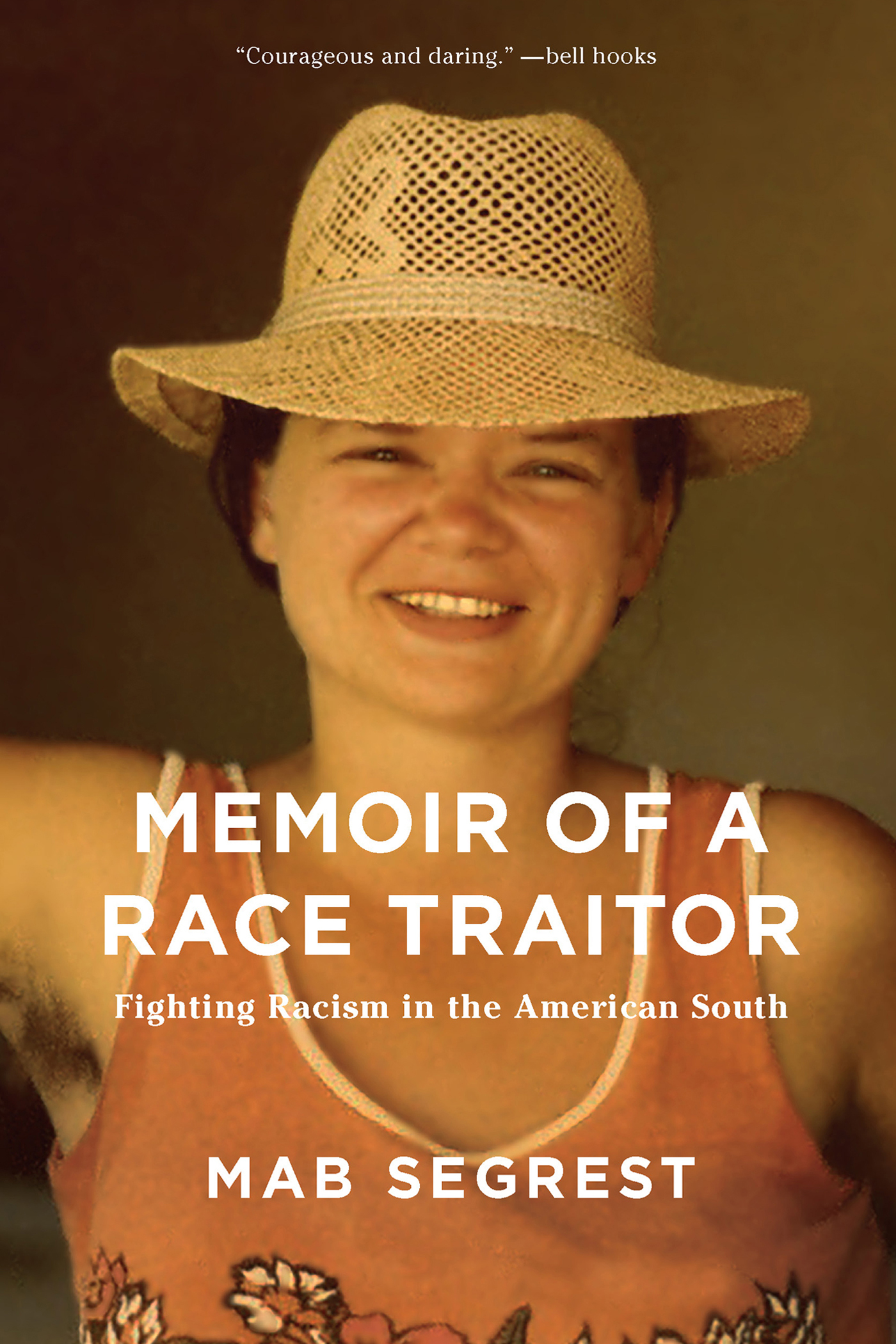

Mab Segrest, the Fuller-Maathai Professor Emeritus of Gender and Womens Studies at Connecticut College, is the author of Administrations of Lunacy: Racism and the Haunting of American Psychiatry at the Milledgeville Asylum (forthcoming from The New Press). She was a fellow at the National Humanities Center and lives in Durham, North Carolina.

ALSO BY MAB SEGREST

Administrations of Lunacy: Racism and the Haunting of

American Psychiatry at the Milledgeville Asylum

Born to Belonging: Writings on Spirit and Justice

My Mamas Dead Squirrel: Lesbian Essays on Southern Culture

Quarantines & Death: The Far Rights Homophobic Agenda

(with Leonard Zeskind)

Sing, Whisper, Shout, Pray: Feminist Visions for a Just World

(with M. Jacqui Alexander, Lisa Albrecht, and Sharon Day)

MEMOIR OF A RACE TRAITOR

Fighting Racism in the American South

Mab Segrest

For Wilson W. Lee

and

John Fletcher Segrest Jr.

Racism is so different from prejudice; it would be helpful if people could begin to use words precisely, giving them their actual meaning. We have scarcely begun to probe this illness. Lets call it what it is: evil. Im not sure it is an illness, it may simply be evil.

Lillian Smith, How Am I to Be Heard?

Contents

Introduction to the New Edition

This year I turned seventy years old. A quarter of a century ago, this book was an alarm bell in the night; now it is clanging louder yet. This is still a story about the ravages of racism, the meanings of race in the United States, and what we must do about them. Race Traitor is also one glimpse into a trajectory of the great battle that still rages in the United States about who controls resources and who is human. It touches us all in intimate ways that white people often have not realized. The memoir part of this book is a story about how that impact of white supremacy happened across generations in my white, conservative southern family. Also, as a treatise on the souls of white people (to borrow W.E.B. Du Boiss phrase), the book was one of the first attempts by a white person to mark the encompassing whiteness that is everywhere on our radar screens, an always present reality that finally comes into sight for us white people as we take it on.

Memoir of a Race Traitor was also written by a lesbian who could not look at race in an uncomplicated way. Rather, it is part of a much larger story about my generation as we variously came out and grappled with what in 1978 the Boston-based Black feminist Combahee River Collective formulated as the particular [generational] task of integrated analysis and practice based upon the fact that the major systems of oppression are interlocking. The Black feminism that Combahee articulated was, its proponents argued, the logical political movement

In 1989, this concept of interlocking and simultaneous oppressions became a basis of what Black feminist critical legal scholar Kimberl Crenshaw termed intersectional feminism. As Crenshaw recently explained, intersectionality is a lens through which you can see where power comes and collides, where it interlocks and intersects, with its primary standpoint the Black and Brown women who are subjected to the multiple effects of systemic power. The intersectional aspect presented the standpoint from which to see; the interlocking part provided the action then required to push through the gates and doors. Locks can be opened, if all the tumblers fall right. The goal was to forge more vital integrities of self, more vibrant communities, and more powerful movements for justice, driven from the margins that become the centers (in bell hookss terms).

But Black feminism also called white women to account for white supremacy, as did the women of color feminism that burst forward in This Bridge Called My Back: Radical Writings by Women of Color, edited by Cherre Moraga and Gloria Anzalda and published by Kitchen Table Women of Color Press. I was one of those white lesbian women who received this charge from my friend Barbara Smith, who was on the Combahee Collective and was an editor at Kitchen Table Women of Color Press. Most notably, Barbara would say, I dont live in the womens movement, I live on the streets of North America. Memoir of a Race Traitor was my attempt as a white person to stand at the intersections of power in order to articulate them in a way that could help figure out how to unlock their tumblers.

The variously gendered queers who are my people brought our struggles into the open during a rising right-wing insurgency that put its scapegoating targets on our backs and tried to make us their political pawns. We did not let them do so: we cared for each other during the AIDS epidemic and, when necessary and now still, walk or carry our loved ones to their graves or cremations.

So from this new edition, hello to old friends. Some of you were there before this books beginning or at its origins. I met many more of you through this book. And welcome, new readers. Many of you will have come of age in the quarter century since Race Traitors first publication, with the years since then bringing their own distinctive set of tumults, from Katrina to 9/11 to the yet unending War on Terror, from the 2008 economic crash to uprising against police shootings to Donald Trumps election. This narrative reads as a precursor to the subsequent dizzying years in which all the plots thickened.

Now white supremacy tweets from the White House in a presidency as surreal as it is just one more f*ing thing. The president is a bag of gale-force winds that blow into the sails of white nationalist movements across the globe. On March 15, 2019, in New Zealand, one of white supremacys foot soldiers brutally attacked two mosques in Christchurch, killing at least fifty Muslim worshippers at prayer while he live-streamed the slaughter on social media to 1.5 million people. In a manifesto posted online before his rampage, he cited the inspiration of recent mass murders by white supremacist terrorists across the globe, including Dylann Roof, who shot to death nine worshippers at Emanuel AME Church in Charleston, South Carolina. He festooned his clothes and weapons with the symbols of neo-Nazi movements and the names of their leaders. Those organizations also maraud through this book.

The killer hailed President Trump as a symbol of renewed white identity and common purpose. White Patriot Party leader Glenn Miller, one of the antagonists of this story, also declared race war in his intersectional diatribe against Niggers, Jews, Queers, assorted Mongrels, white Race traitors, and despicable informants, declaring in 1987: And so, fellow Aryan Warriors, strike now. Keep reading to see his results. Glenn Miller now sits on death row in Kansas after a 2014 attack outside a Kansas City Jewish community center in which he murdered three people.

Of course, in the New Zealand attacks against Muslims praying in their mosques, the antecedent is much older than the U.S. Civil War. Its the Crusades.

A quarter of a century after the initial publication of Memoir of aRace Traitor, the stakes are higher, the waters are rising, and so are our resources, our solidarities, and our insistence.

As one marker of time, I spent the greater part of March 11, 2019, in Raleigh, North Carolina. I was there at the Wake County courthouse to support people who were arrested on November 23, 2018, after Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) seized Samuel Oliver-Bruno from his familyhis wife and his nineteen-year-old son. On November 23, 2018, Samuel left eleven months sanctuary in CityWell Methodist Church to go to the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) office in Morrisville, outside of Raleigh, as part of a scheduled appointment to move forward his application for reprieve of deportation. Knowing the dangers of this journey, CityWell congregants caravanned with Samuel to the USCIS office, where dozens of other supporters waited. So did undercover ICE officers, who had collaborated with USCIS prior to the appointment. Once Samuel was inside the office, undercover ICE agents tackled him, and other ICE agents appeared from behind closed doors to haul Samuel to a waiting ICE van. His son, Daniel, was charged with assault on a government official for refusing to let go of his father in the tumble, holding on as all children do when faced with separation from a loved parent. After ICE moved Samuel to its van, protesters surrounded the vehicle, arms locked and singing, extending the sanctuary of the church building to the streets for as long as they could. Three hours later, the twenty-seven people surrounding the van were arrested and Samuel was taken into detention.

Next page