Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

To those whose stories of hope and resilience inspired this book.

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

Everybody Matters: My Life Giving Voice

CONTENTS

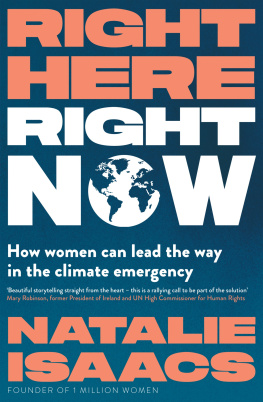

On the night of November 11, 2016, in a guesthouse in the ancient medina of Marrakech, I was having difficulty sleeping. I had arrived that evening on a flight from Paris to attend the UN annual climate change talks. One year earlier, the signing of the Paris Agreement had marked a critical turning point towards a zero-carbon, more resilient world. Now, representatives from 195 nations, including the United States, were gathering in this Moroccan city to discuss ways to implement the agreement.

After a late-night dinner and debrief with my foundation team, Ireland twenty-six years earlier to the day.

In the previous weeks leading up to Marrakech, as my small team and I worked long hours at our office in Dublin in preparation, I had kept a close eye on the electoral race playing out across America. As Election Day approached, I became increasingly anxious about the prospect of a Trump victory. I was deeply concerned by Trumps anticlimate change rhetoric and his promise to pull the United Statesthe worlds most powerful nation and the biggest carbon polluter in historyout of the Paris Agreement, which had come into force just four days before the election. One of the greatest international achievements in multilateral diplomacy, the agreement was a shining example of how the world could come together to combat an existential global threat. How would Trumps election affect the resolve of other countries in Marrakech? In my heart, I knew that the Paris Agreement was stronger than any one nation, yet I felt foreboding at the prospect of this new U.S. administration.

So much was at stake. For more than a decade, I had met those suffering the worst effects of climate change: drought-stricken farmers in Uganda, a president struggling to save his sinking South Pacific island nation, Honduran women pleading for water. They come from communities that are the least responsible for the pollution warming our planet, yet are the most affected. They are often overlooked in the abstract, jargon-filled policy discussions about how to address the problem. But their stories have made me realise that the fight against climate change is fundamentally about human rights and securing justice for those suffering from its impactvulnerable countries and communities that are the least culpable for the problem. They must also be able to share the burdens and benefits of climate change fairly. I call it climate justiceputting people at the heart of the solution.

The next morning, I awoke in Marrakech resolute on a course of action: I would issue a statement urging the United States to stay the course and to withstand any efforts by a Trump White House to derail the Paris Agreement. Over breakfast, I discussed my plan with the director of my foundation, who voiced caution. Next, I called my husband, Nick, my mentor and great ally, who was at our home in county Mayo, Ireland. Nick listened to my proposal and then gently advised me not to make a speech or statement, suggesting that it would be counterproductive to take such a sharply critical tone. Still determined, I called my friend and close adviser Bride Rosney in Dublin. I understand how you are feeling, Mary, Bride told me. You need to get this out of you, but you need to do it the right way. All you need is a journalist to ask you the right question.

Later that morning, in a quiet corner away from the bustle of the climate talks, I spoke on camera with Laurie Goering from the Thomson Reuters Foundation. Fighting back emotion, I described how, as United Nations Envoy for El Nio and Climate Change, I had recently met women in the drought-stricken regions of Honduras who no longer had water. I had seen the pain on the faces of those women. And one of the women said to me, and Ill never forget, We have no water. How do you live without water?

Laurie moved the mic nearer and I expressed my pent-up feelings: It would be a tragedy for the United States and the people of the United States if the U.S. becomes a kind of rogue country, the only country in the world that is somehow not going to go ahead with the Paris Agreement. The moral obligation of the United States as a big emitter, and historically an emitter that built its whole economy on fossil fuels that are now damaging the worldits unconscionable the United States would walk away from it.

I felt lighter as the interview drew to a close. It was a relief to speak my mind and to define the moral issue at stake. I remembered something the poet Seamus Heaney wrote to me on the day that I became the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights: Take hold of it boldly and duly.

By weeks end, the ripple effects of the election had dissipated across the tented canopies of the climate talks, and my fears were diminished. Nation after nationin union with civil society and business leadersreaffirmed their commitments to the Paris Agreement. Behind closed doors the meeting buzzed with a renewed sense of urgency. Along the corridors of the climate talks, housed on the dusty outskirts of Marrakech, people moved with more energy. On the final day, forty-eight of the poorest countries made an extraordinary pledge: They would receive all their energy from renewable sources by 2050. Having some of the countries most vulnerable to climate change lead on delivering the goals of Paris was a powerful and humbling declaration. The message was clear: There was no turning back. The rest of the world would forge ahead with or without the United States.

On December 12, 2003, my thirty-third wedding anniversary, I was at a meeting in Trinity College Dublin when my cell phone rang. It was my son-in-law, Robert, breathless with news. My daughter, Tessa, had just given birth to their first child, a boy. Could I come to the hospital, Robert asked, and meet my first grandchild?

I grabbed my coat and stepped out into the brisk winter air. It was a ten-minute walk from Trinity College through the heart of Georgian Dublin to Holles Street and the national maternity hospital, where, thirty-one years earlier, I had given birth to my own first child, Tessa herself.

In the hospital ward, I embraced the exhausted but elated couple. Tessa tenderly passed me a tiny bundle and watched with delight as I peered inside. Face-to-face with my grandson, Rory, I was flooded with a rush of adrenaline, a physical sensation unlike anything I had ever felt before. In that moment, my sense of time altered and I began to think in a time span of a hundred years. I knew instinctively that I would now view Rorys life through the prism of our planets precarious future. I made a quick mental calculation: In 2050, when Rory would be forty-seven, he would share the planet with more than nine billion people. These billions would be seeking food, water, and shelter on a planet already suffering the effects from our global dependency on fossil fuels. What would that world be like? Would we have pushed ourselves by then to the verge of extinction? The abstract data on climate change that I had skirted around for so long suddenly became deeply personal. Holding this tiny baby, I instantly felt the threat that climate change could pose to himand thereby to all humanity. I would be long gone by 2050, but what could I do to help ensure that Rory, and every other baby born in 2003, would inherit a world fit to live in, and not one on the brink of despair?