For Africas youth strikers.

I hear you.

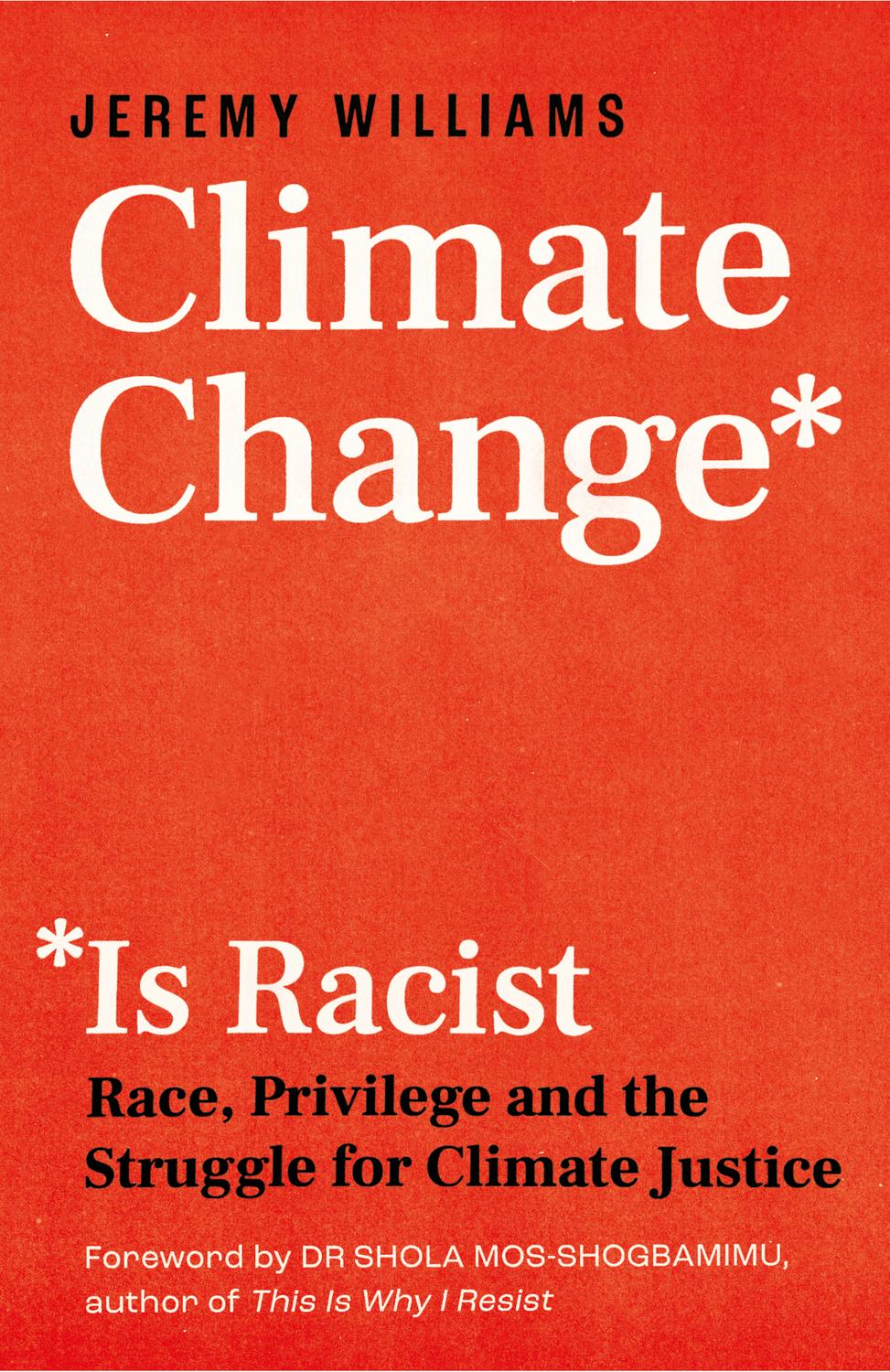

There will undoubtedly be people who get stuck on the book title Climate Change Is Racist. But the undeniable truth is that climate change, as a global existential crisis, exacerbates racial inequality and racial injustice and its vital that people understand how and why. The good news is that Jeremy Williams has taken on this task, clearly explaining the link between the climate crisis and systemic racism for those who may not have seen the connection.

The conversational style of Jeremys writing will open the minds of even the most ardent denier of climate change and/or systemic racism. He helps us understand that climate change not only coexists with racism, but intersects with racial inequality. Everything we value as a necessity is susceptible to the impact of global warming from water, food, health and wildlife to the economy, energy and transport, to name a few. Now consider the significant impact of systemic racial inequality, which already discriminates access to these vital resources on the basis of racial superiority. As I discuss in my own work, racism is a power construct created by White nations to benefit White people. It is fuelled by an unparalleled economic and political structure controlled by White nations, the by-product of which is White privilege an advantage solely based on being White xii and not predicated on socioeconomic status, class or heritage. All of which denies Black and Ethnic minorities an equal value of life and liberty. This means that systemic racism will make the impact of climate change unequal. We will not all suffer climate change the same.

The United Nations calls climate change the defining issue of our time. This is true, because of how global warming impacts everything we value and depend on. However, the missing link here is that those who will first, and ultimately, pay the price for the devastating impact of climate change are those already bearing the brunt of racial inequality. This is why we cannot talk about climate justice without talking about racial justice. This includes the marginalised voices of women, particularly Black and Ethnic Minorities who face worsening inequalities because their lives and livelihoods are at risk.

Jeremy unpicks the potential failure of global nations to prepare for a global climate change catastrophe and shows why racism is a key component. The coronavirus pandemic took the world by storm in 2020 and caused the exacerbation of longstanding racial inequality, evidenced by high tolls of deaths from Black, Asian and Ethnic Minority communities in developed countries, which are apparently more industrialised and economically advanced. The impact of climate change will be a global catastrophe incomparable to any other urgent humanitarian crisis in recent history. Without drastic action to eradicate the roots of systemic racism, humanity is creating the blueprint for devastation and destruction of epic proportions. To prevent xiii and fight this calamity, climate action must be inclusive of antiracist action.

Hard work is necessary to deconstruct structural racial inequality as a global issue between White nations and Black/Brown nations and to understand the impact of the climate crisis in deepening long-standing structural inequalities between these nations, and between White and Black/Brown people within White nations. If theres one book that will help you to be an effective activist for climate justice, it is this one.

Dr Shola Mos-Shogbamimu

Lawyer, Political & Womens Rights Activist,

Author, This Is Why I Resist

M y desk is made of scrap wood, in a makeshift office in the attic. This is as far as I can get from the lockdown home-school currently running at the dining table, and it is just about far enough to concentrate.

The last chapters of this book have been written under very different circumstances to the first, not just due to the challenges of a global pandemic. Events in America have catapulted racial justice up the agenda. When I started my research, there were relatively few people talking about climate and race. Today, I see articles making the connection on a regular basis.

The book turns out to be timely and urgent, though I almost didnt write it at all. I talked myself out of it, and then back in again. I wasnt sure if it was my book to write, but ultimately I had seen something I could not unsee. As I look out my attic window and reflect on my own story, I can almost pinpoint the moment I saw it first.

So this is what it feels like to be racially abused

Nairobi, 1998. I was seventeen, and attending a boarding school in Kijabe, Kenya. My friend Mark and I were in the capital for the weekend to watch the Safari Sevens international rugby tournament. We caught one of the citys notorious matatus a xvi vibrantly painted, riotously driven minibus. Theres no schedule. It goes when its full, and we crammed in and bunched up to let more passengers on board.

Half an hour later we could see the sports ground up ahead, and we left our seats and squeezed past other passengers to the door. The bus pulled in, a couple of others got off, and thats when the trouble started. The bus conductor, a young man in his twenties, wouldnt let us off the bus. No! he shouted. Not you.

This is our stop, I protested, but he reached out his hands and pushed me and my friend in the chest. We both stumbled backwards into the seats nearest the door. The bus moved on. A hundred yards later, we tried again at the next stop. Again we were pushed back down. You get off when I tell you to get off.

The bus moved again, and now the conductor started to shout. His rant was partly directed at us, partly at the rest of the bus, sometimes at the world at large. My knowledge of Swahili was poor, but I knew enough to recognise mockery when I heard it. There was nervous laughter from the rest of the bus, but otherwise nobody said anything. Stop after stop he went on, pointing and gesticulating. We stopped asking to get off. We were silent, frozen. We were just going to have to sit this out.

The longer the conductor went on, the angrier he became. We seemed to have become the lightning rod for all this mans many grievances, and there was mounting violence in his eyes. At one point he leaned in and shouted right in our faces. I felt his spittle hit me, and I was too scared to wipe it off. I was convinced that a strike was coming.

xvii It didnt. He shouted himself hoarse and finally fell quiet. He said nothing for several minutes, standing in the open doorway and staring out at the passing streets. Then the bus pulled in again, and he jerked his head at us. We got out. The bus was on a circular route, and we were right back where we had started.

Feeling rather shaken, we lined up for another bus.

The privilege of surprise

It wasnt the first time I had been harassed for being White, but in five years living in Kenya, it was the first time I had felt a genuine threat of violence. Whites were usually treated with post-colonial deference and an assumption that we were well off and well-connected. This kind of abuse was unexpected, and it caught me by surprise. The incident stands out because it was so unusual, and, with hindsight, I can recognise that surprise as a privilege. For many, being harassed on a bus is expected. It is unsurprising, perhaps even normal.

If you had asked me at seventeen, I would have told you that racism in 1990s Kenya was a reality. But Id have said that I wasnt racist myself and that racism did not affect me. It was not a part of my world, I was not complicit, and thats why it was such a shock to be racially abused.