CLIMATE CHANGE FROM THE STREETS

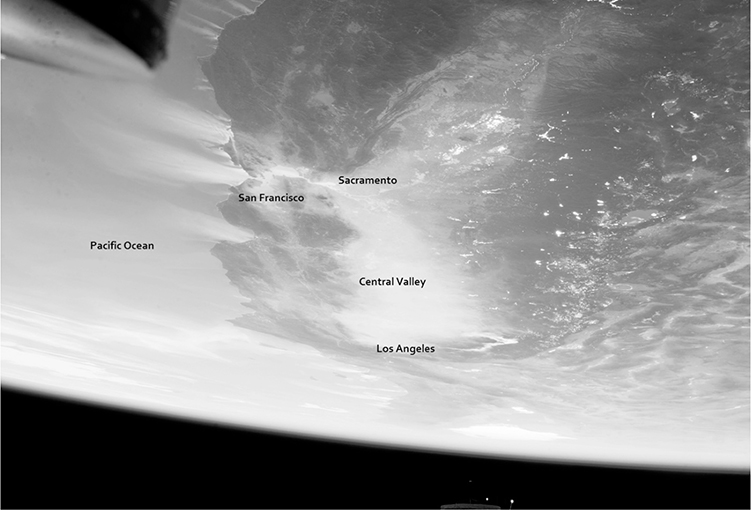

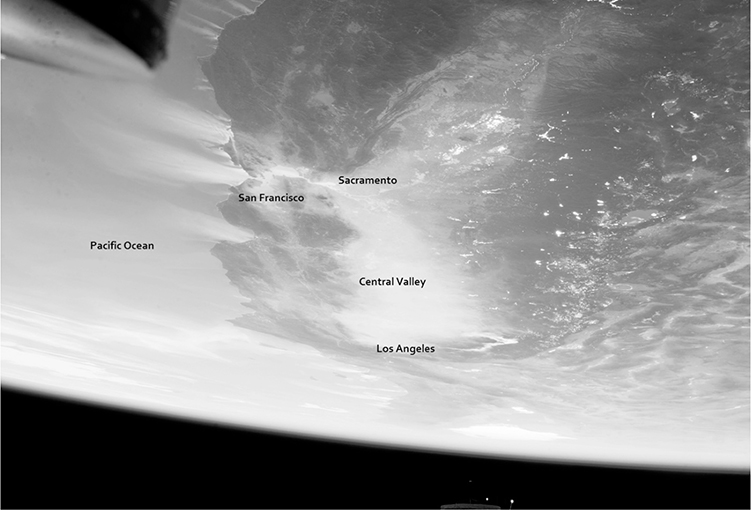

An astronaut aboard the International Space Station photographed the thick layer of smog that hovered over many regions of California in the winter of 201314. Courtesy of NASA JSC Earth Science and Remote Sensing Unit

CLIMATE

CHANGE

FROM THE

STREETS

How Conflict and Collaboration Strengthen the Environmental Justice Movement

MICHAEL MNDEZ

Published with assistance from the foundation established in memory of Calvin Chapin of the Class of 1788, Yale College, and with the assistance of the Frederick W. Hilles Publication Fund of Yale University.

Copyright 2020 by Michael Mndez.

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail sales.press@yale.edu (U.S. office) or sales@yaleup.co.uk (U.K. office).

Set in Janson type by Integrated Publishing Solutions.

Printed in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2019940371

ISBN 978-0-300-23215-8 (hardcover : alk. paper)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992

(Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Sometimes it is the people no one imagines anything of who do the things that no one can imagine.

ALAN TURING (attributed)

Contents

Preface

T HIS BOOK IS ABOUT people, place, and power in the context of climate change and inequality. Although the science of climate change is clear, policy decisions about how to respond to its effects remain contentious. Even when such decisions claim to be guided by objective knowledge, they are made and implemented through political institutions and relationshipsand all the competing interests and power struggles that this implies. I tell a story about the perspectives and influence that low-income people of color bring to their advocacy work on climate change. They are making their voices heard despite the structural disadvantages that often exclude them from public debate. For them, the main threat from climate change is the disproportionate harm that it causes to health in their communities, including an increase in illnesses, injuries, and deaths from extreme events such as hurricanes and wildfires and a rise in respiratory diseases caused by degraded air quality that is further worsened by prolonged drought.

This insight leads them to view climate change as an embodied phenomenon that affects peoples daily lives in multiple ways. Recognition of these dynamics is shifting discussions about the broad effects of climate change. Debates are emerging on the unequal harm that it already causes to certain people and communities. This book unpacks the argument that environmental protection and improving human health are inextricably linked, and maintaining that link is key to advancing future climate action policies.

The importance of such links was profoundly apparent to me in the winter of 201314, during daily four-mile runs along the Sacramento River, which parallels busy Interstate Highway 5. Over time, those runs began to take a heavy toll on my chest, an effect of the pollution that was accumulating during one of the driest winters on record. From Los Angeles to Sacramento, a haze of gray particles hung in the air. For more than a month, the haze, visible from outer space, obstructed the view of the Sierra Nevada mountain range. Simultaneously, a high-pressure ridge, four miles high and off the West Coast, prevented Pacific storms from cleansing the air. With no rain since early December 2013, pollution levels spiked. In the San Joaquin Valley, Californias agricultural heartland, airborne fine particulate matter accumulated to unhealthy levels. Conditions continued to deteriorate until sporadic rain showers came in late January 2014. During these dry winter months, air quality officials declared red alert days and warned people to stay indoors. On one red alert day, I ignored the warning and took my daily run. By the third mile, my head had started to ache, and I had begun coughing heavily. Feeling anxious, I stopped to catch my breath and walked the last mile home.

Research by Noah Diffenbaugh and colleagues, published in the Proceedings of the National Academies of Sciences, concluded that the states drought conditions are far more likely to occur in todays warming world than in one without human-caused emissions of greenhouse gases. In light of global climate change, it is projected that by the end of the century California will experience a much greater number and severity of dry, hot-weather seasons. According to climate scientists, the resultant droughts, heat waves, and wildfires can all have a profound effect on air quality. During heat waves and droughts, the air becomes stagnant and traps emitted pollutants, often resulting in increases in surface ozone that can accelerate smog formation. These extreme weather events can also prolong the wildfire season by drying out vegetation and providing more fuel for wildfires, whose smoke is a serious public health threat. State policymakers have referred to these climate changeinduced trends as the new abnormala state of perpetual climate crisis that has the potential to continue for generations.

Red alert days thus represent a rapidly changing climate in California. Air quality warnings were previously issued only in the summer and directed at sensitive populations, such as children, the elderly, and those with respiratory problems. More recently, however, warming temperatures, wildfires, and extreme drought conditions mean increased health risks for everyone. In the San Joaquin Valley, where air quality has deteriorated over recent decades, school officials have long flown colored flags to indicate air conditions: green for good; yellow, moderate; orange, unhealthy for sensitive groups; and red, unhealthy for all population groups. By January 2014, declining air quality forced officials to introduce a new flag color: purple. It indicated very unhealthy air for everyone. When a purple alert was declared, schools were forced to fly red flags because they had no purple flags. Until then, such flags had never been needed. The purple alert banned all outdoor activity for teachers and 30,000 students in the Bakersfield City School District. In the district, 91 percent of the population are students of color, 30 percent are classified as English language learners, and almost 90 percent of the students receive free or reduced-price lunches. According to a local elementary school principal quoted in the Portville Recorder, that winter was the first time ever we have been on an inside schedule when it is cold outside. Usually we see this kind of thing when it is hot. Not in January. Yet such poor air quality is not restricted to the San Joaquin Valley. When California entered its third consecutive year of extreme drought in 2014, weather patterns helped create some of the highest levels of soot in the metropolitan regions of Los Angeles and San Francisco.

These smoggy winter skies recall a period in the 1950s and 1960s when Californians endured conditions similar to those now faced by residents of New Delhi or Beijing. Experts predict that extreme weather associated with climate change could reverse decades of efforts to improve the states air quality. With these implications in mind, one of the oldest and best-known medical journals, the

Next page