This landmark series interprets broadly the history and culture of the Civil War era through the long nineteenth century and beyond. Drawing on diverse approaches and methods, the series publishes historical works that explore all aspects of the war, biographies of leading commanders, and tactical and campaign studies, along with select editions of primary sources. Together, these books shed new light on an era that remains central to our understanding of American and world history.

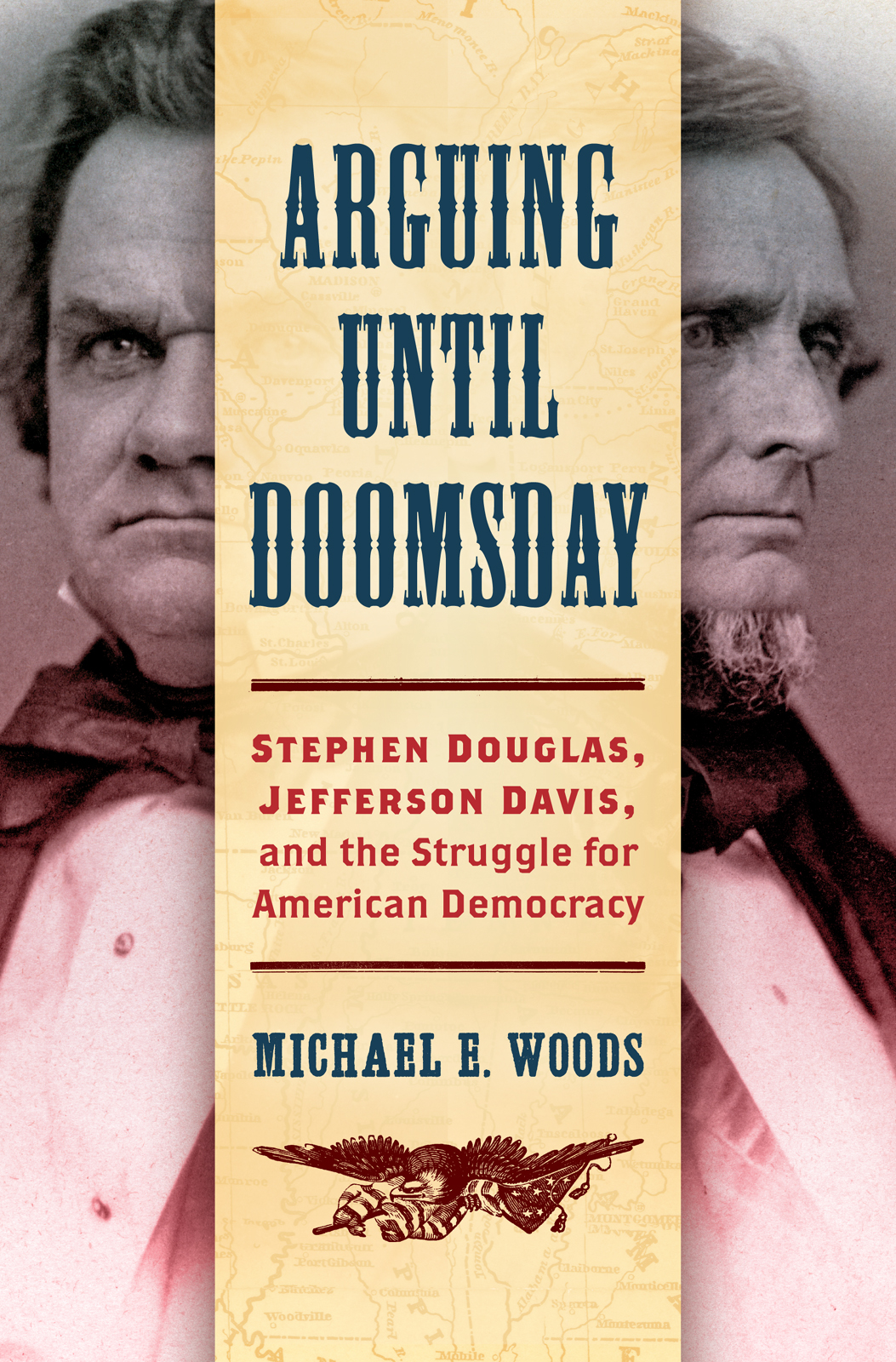

Arguing until Doomsday

Stephen Douglas, Jefferson Davis, and the Struggle for American Democracy

Michael E. Woods

The University of North Carolina Press

CHAPEL HILL

This book was published with the assistance of the Anniversary Fund of the University of North Carolina Press.

2020 Michael E. Woods

All rights reserved

Designed by Kristina Kachele Design, llc

Set in Miller Text with Directors Gothic 210 display by Kristina Kachele Design, llc

Manufactured in the United States of America

The University of North Carolina Press has been a member of the Green Press Initiative since 2003.

Jacket illustrations: portraits of Stephen Douglas and Jefferson Davis by Julian Vannerson, photographer, 1859, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division; (background) U.S. map by Rufus Blanchard, 1856, Library of Congress Geography and Map Division.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Woods, Michael E., author.

Title: Arguing until doomsday : Stephen Douglas, Jefferson Davis, and the struggle for American democracy / Michael E. Woods.

Other titles: Civil War America (Series)

Description: Chapel Hill : The University of North Carolina Press, 2020. | Series: Civil War America | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019044427 | ISBN 9781469656397 (cloth) | ISBN 9781469656403 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Douglas, Stephen A. (Stephen Arnold), 18131861. | Davis, Jefferson, 18081889. | Democratic Party (U.S.)History. | SlaveryHistory19th centuryPolitical aspectsUnited States. | United StatesPolitics and government18451861. | United StatesHistory17831865.

Classification: LCC JK2316 .W74 2020 | DDC 973.7/11dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019044427

This project is being presented with financial assistance from the West Virginia Humanities Council, a state affiliate of the National Endowment for the Humanities. Any views, findings, conclusions, or recommendations do not necessarily represent those of the West Virginia Humanities Council or the National Endowment for the Humanities.

For Beth

Contents

Figures

Arguing until Doomsday

Introduction

Alfred Iverson was sick of congressional gridlock. The Georgia senator had endured four years of divisive votes, bombastic speeches, and violent disturbances. Now, in February 1859, as two fellow Democrats bickered away a Wednesday afternoon, his patience ran out. Other senators had tried to gain the floor, but even when David Broderick of California succeeded on his sixth attempt, the combatants kept sparring. As winter twilight settled over the capital city, Iverson urged the presiding officer, Florida senator Stephen Mallory, to enforce the rule that limited senators to two comments per topic. Normally, said Iverson, he would cheerfully allow the loquacious senators to wrap up, but one of them had spoken at least six or eight times on this subject and his adversary nearly as much. If we permit these gentlemen to go on bandying arguments with each other, Iverson warned, we shall never come to the end of the question. They can go on here arguing against each other from this until doomsday.

Iverson drew laughs, but the situation was deadly serious: Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois and Jefferson Davis of Mississippi had spent three hours clashing over property rights, democracy, and the future of the American West. Their battle had erupted over a seemingly routine matter. The previous day, the Senate had taken up House Bill 711, an appropriations bill to fund the federal government through June 1860. Debate remained comfortingly dull until New Hampshire Republican John P. Hale proposed an amendment seeking repeal of an older provision to delay the Kansas Territorys statehood until its population reached the minimum required for one congressional representative. Stunned, other senators demanded to know why Hale would broach this fraught subject with the session nearly over and much work still undone. But Hales amendment was relevant: H.B. 711 earmarked $20,000 for a territorial census. So, senators wrangled over Kansas for the rest of the day, proving only that no one knew how many people lived in the distant, bloodstained territory.

The fireworks began Wednesday when the Senate returned to Hales amendment and dropped all pretense of discussing anything but slavery. Mississippis Albert Gallatin Brown opened with a blistering demand that Congress enact a federal slave code if territorial legislatures failed to safeguard slaveholders property rights. He swore that if the North, by mere force of numbers, denied slaveholders their rightful protection, then the Constitution is a failure, and the Union a despotism, and he would support secession.

This was too much for Stephen Douglas. After glancing around the new Senate chamber, in use for little more than a month, and finding no fellow northern Democrat willing to respond, the Little Giant from Illinois raised his rotund, five-foot-four-inch frame to reply. He first sought common ground with Brown, agreeing that slaves were property and that citizens could carry property into the territories. But that was the end of their agreement. Brown wanted to give slaveholders special federal protection; Douglas demurred. Slaves were subject to local regulation like any other type of property, he insisted, and if masters needed federal help, it was their misfortune and none of his own. According to Douglass pet doctrine of popular sovereignty, property rights did not trump territorial self-government. After parrying counterattacks from Brown and Alabamas Clement Clay, Douglas threw down the gauntlet: no slave code crusader could call himself a Democrat, for such an agenda violated the Democratic creed. Glancing ahead to next years presidential election, he added that no Democrat who favored proslavery federal intervention could win a single northern state.

With that, Jefferson Davis plunged into the fray. Maintaining a stiff military bearing despite the neuralgic pain searing his face, Davis hurled back the threat of excommunication, wishing Douglas God-speed and a pleasant journey if he insisted on popular sovereignty. The Constitution, Davis insisted, did recognize slaves as a unique form of property. Congress, he proclaimed, was duty-bound to safeguard masters property rights in the territories. And if Democrats split over the status of a few Africans, Davis wanted it known that he condemned Douglass apostasy.