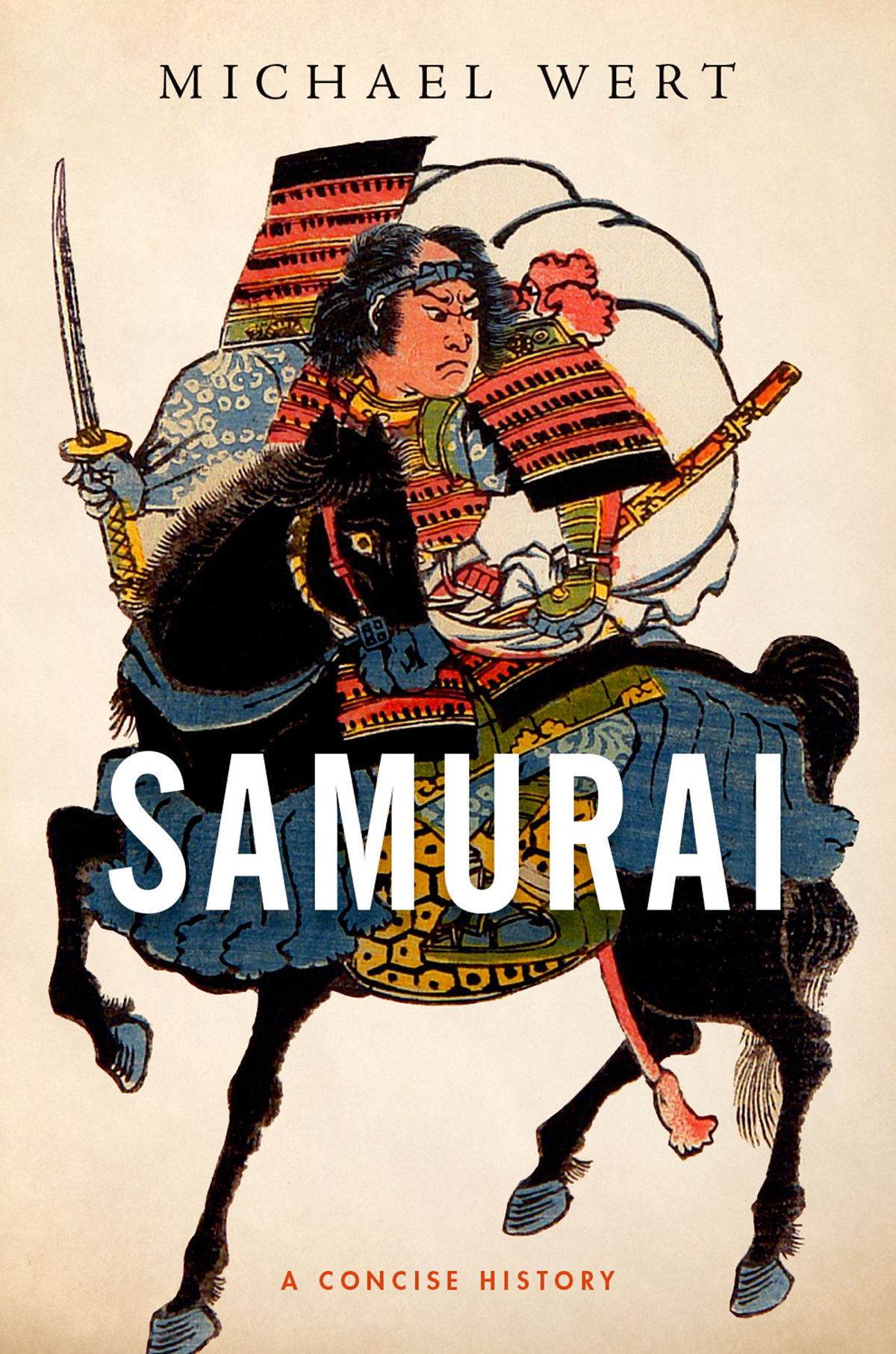

Michael Wert - Samurai

Here you can read online Michael Wert - Samurai full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2019, publisher: Oxford University Press, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Samurai

- Author:

- Publisher:Oxford University Press

- Genre:

- Year:2019

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Samurai: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Samurai" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Samurai — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Samurai" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

Oxford University Press 2019

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

CIP data is on file at the Library of Congress

ISBN 9780190932947

eISBN 9780190932961

To my wife, Yuko Kojima Wert

In the climactic battle scene at the end of the movie The Last Samurai (2003), the protagonist, a samurai rebel, leads his army of warriors as they charge to certain death against the newly formed, modern government army. Wearing only their traditional clothing and armed with bows, swords, and spears, they are mowed down by Gatling guns and howitzers as the governments general, himself an ex-samurai, looks on anxiously. This scene has all the familiar tropes in the global fantasy about samurai: tradition versus modernity, hand-to-hand fighting versus guns, and a celebration of honorable death. The event depicted in the film is a historical one, the War of the Southwest in Japan in 1877, when ex-samurai refused to follow a series of laws that stripped all samurai of their privileged status and accompanying symbols; no more wearing swords in public or maintaining topknot hairstyles. A more accurate description of the battle scene flips the cinematic onethe modernized government army took shelter in a castle, the most traditional of defenses, while ex-samurai rebels bombarded them with cannon from outside. As with anything else, the historical depiction is more interesting than the popularized one.

Samurai seem ubiquitous in popular culture; from the novel and television show Shogun (1980) to The Last Samurai and the animated series Samurai Champloo (20042005), audiences never seem to tire of them. They even appear in the most unlikely places; the corporate name of a local coffee shop chain in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, is Giri, which the founder claims comes from the Samurai code of honor, Bushido, and can be translated to mean social obligation. It sounds nice, but obligation was simply a way to convince samurai to obey their lords no matter the danger or, more likely, the drudgery.

There is no shortage of websites on samurai, and one can hardly throw a rock without hitting some martial art instructor with a distinctive view on the samurai. There are plenty of glossy books that give an overview of some aspect of samurai battles, warfare, castles, and the like, but sifting through what is reliable and what is not can be a chore. On the other hand, scholarly books tend to require too much background information, familiarity with not only Japanese but also Chinese history, religion, and art, disciplinary jargon, and, for some older history books, significant language commitment.

I will describe how samurai changed from, roughly, the eighth to the mid-nineteenth centuries, impart a sense of warrior diversity, and dispel common myths, such as the so-called bushido samurai code, swords as the soul of the samurai, and supposed fighting prowess. Not all periods of warrior history are covered equally; there are more details of samurai life from the seventeenth through nineteenth centuries (the early modern period) because most depictions of samurai in the West coincide with warriors from that period, and scholars know more about early modern Japan than about the medieval period (ninth through fifteenth centuries). There are so many documents from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries that one can buy them on internet auction sites for tens of dollars. A recent auction for a collection of hundreds of documents from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, belonging to a single family, sold on Yahoo Auction for 73,000 yen, about $660. Some texts from early modern Japan even end up in the trash. After the earthquake, tsunami, and Fukushima nuclear disaster on March 11, 2011, local historians scrambled to photograph historical documents found in dilapidated storehouses slated for destruction and rebuilding. There were so many documents that local museums and universities did not have room to keep those deemed unimportant, and hence they risked being thrown out. Documents from before the seventeenth century are occasionally discovered but in ever fewer numbers, and they are treated with greater care.

A final word about conventions. In Japanese, the surname precedes the given name. I use the term warrior for the ninth through sixteenth centuries, and samurai for the seventeenth through nineteenth centuries, when they existed as a narrowly defined social status group. Warlord and lord both refer to daimyo, military leaders who held territory and engaged in warfare during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, but by the early seventeenth century, they had become decidedly un-warlike governors. In other words, I split warrior history into two imperfect halves, the medieval and early modern periods, with the early seventeenth century as the dividing line. That is when the category of warrior narrowed, fundamentally changing for this group their culture and relationship to the rest of the Japanese population.

Colloquially, even in Japan, the term samurai is used as a synonym for warrior, but this is incorrect. Samurai originally had a very narrow meaning, referring to anyone who served a noble, even in a nonmilitary capacity. Gradually it became a title for military servants of warrior familiesin fact, a warrior of elite stature in pre-seventeenth-century Japan would have been insulted to be called a samurai. There were other more common terms for warriors in classical and medieval Japan that reflected their various duties to the state, nobility, and other superiors. Most specialists in Japan and in the West use the generic term bushi, which means warrior.

Warrior is a usefully ambiguous term for referring to a broad group of people, before the seventeenth century, with some military function. This includes anyone expected to provide military service to the state when needed and who received official recognition from a ruling authority to do so, such as the nobility and court in Kyoto or religious institutions. Even the term warrior is imprecise because it incorrectly suggests that warfare was this groups sole occupation. Depending on the time period and status, warriors alternatively governed, traded, farmed, painted, wrote, tutored, and engaged in shady activities.

No such code existed. Even phrases used ironically assume the existence of an authentic admirable warrior imagefor example, weekend warrior, suggesting that one is a normal boring person during the week but becomes some other, more primal person on the weekend. In this usage, a warrior is something one

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Samurai»

Look at similar books to Samurai. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Samurai and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.