This eBook edition 2013

First published in the UK in 2012 by

Duckworth Overlook

30 Calvin Street, London E1 6NW

Tel: 020 7490 7300

www.ducknet.co.uk

1995 by Hiroaki Sato

Illustrations 1995 by Murakami Tamotsu

All rights reserved. No part of this publication

may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or

transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic,

mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise,

without the prior permission of the publisher.

A catalogue record for this book is available

from the British Library

ISBNs

Paperback: 978-0-7156-4363-1

Mobipocket: 978-0-7156-4437-9

ePub: 978-0-7156-4436-2

DEDICATED TO

Rand Castile

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

AND NOTES

The Abe Family first saw print in the Fall-Winter 1977 issue of St. Andrews Review. I wish to thank Ron Bayes, founder and editor of SAR, a gallant magazine which fulfilled its mission and folded in late 1991.

Part of the Introduction and the section on Oda Nobunaga were originally a speech entitled The Samurai and Poetry, given on February 19,1992, at Cornell University.

For the English translations of official titles I generally followed Ivan Morris in The Pillow Book of Sei Sh nagon, vol. 2. But where I found his equivalent unacceptable, as in calling the second-ranking officer in the Imperial Police assistant director, I devised my own. For different translations of certain titles, see Karl Fridays book on the early samurai, Hired Swords.

nagon, vol. 2. But where I found his equivalent unacceptable, as in calling the second-ranking officer in the Imperial Police assistant director, I devised my own. For different translations of certain titles, see Karl Fridays book on the early samurai, Hired Swords.

Of many such titles that appear in the accounts, governor (kami) must be viewed with the most caution. At first designating someone appointed to head a province, governorship was a position of substantial revenues and prestige perhaps until the early twelfth century. Thereafter the title gradually lost substance and became nominal until, with sporadic exceptions, it all but lost the original sense of governance. The reader should not be surprised to see governor attached to some of the men working for warlords.

Many of the stories, accounts, and arguments cited in this book are accompanied by running commentary, as well as notes. Some historical facts and other background information, such as the birth and death dates of the people concerned, are repeated so as to make each context easy to understand.

In most instances brackets indicate that the information given in thembe it date, name, or noteis supplied by me.

In giving dates before the mid-nineteenth century I have followed the custom of rendering the lunar calendar in English-for example, the first month rather than January as in the solar calendar. I have given Japanese and Chinese names as they are given in Japan and China, family name first.

In the old days Japanese of rank and status usually had more than one name. At times any of the personal names and the family name were used interchangeably, without gaining or losing respectability, as in the case of Kusunoki Masashige, who is sometimes called by the family name, Kusunoki, sometimes by his personal name, Masashige.

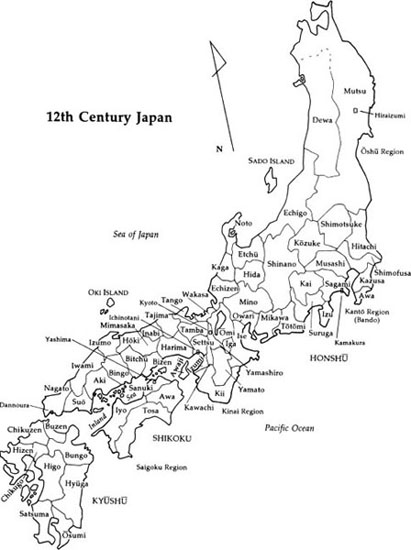

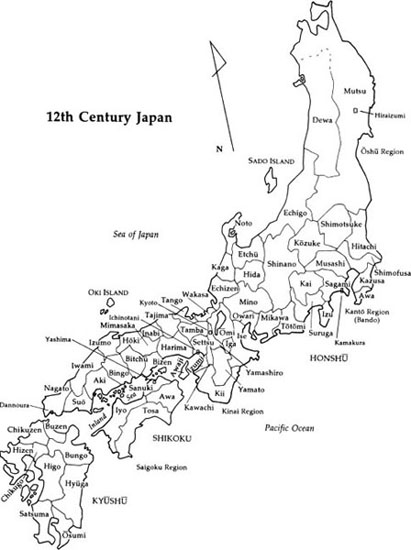

I wish to thank Kinoshita Tetsuo, Hirata Takako, Fujii Sadakazu, and Fujii Misako for acquiring necessary texts and books, and Deborah Baker and Jessika Hegewisch, my earlier editors on this book at The Overlook Press, for reading initial sections of the manuscript. Nancy Rossiter read the manuscript as it was completed chapter by chapter. She also prepared the maps on the basis of one of the maps in Hired Swords, with permission of Stanford University Press. Kyoko Selden read the finished manuscript and gave me helpful comments; so did my meticulous editor friend, Eleanor Wolff.

I thank Murakami Tamotsu for preparing the picture depicting Kusunoki Masashige for the cover and six illustrations.

Above all, Robert Fagan spent many days and nights on the manuscript for a period stretching over eight years. I am grateful that he never gave up.

A samurai with a deep, wide-brimmed hat is walking through an apparently deserted field. Suddenly, more than a dozen bandits with drawn swords spring out of the surrounding grass, encircle him, and demand prompt surrender of his swords and other valuables, or else. The samurai indicates compliance and starts to take off his haori, the outer jacket, and the bandits relax a little. That instant he draws his sword and cuts down ten or so of them with lightning speed. The remaining few run away, screaming for their lives. The samurai takes out a tissue from his breast, wipes the blood off his sword, puts the sword back into its sheath, and resumes his walk as if nothing has happened.

Or

A famous swordsman visits a daimyo at his mansion. A r nin, a master-less samurai, who happens to be staying there, is confident of his own swordsmanship; upon learning who the visitor is, he asks him to teach him some fighting techniques. Teaching is a euphemism for a serious match. The swordsman declines. But the daimyo shows interest, and at his urging the swordsman finally agrees to fight with wooden swords. Out in the garden the two men face each other and a moment later strike with their wooden swords hitting each others body, apparently simultaneously.

nin, a master-less samurai, who happens to be staying there, is confident of his own swordsmanship; upon learning who the visitor is, he asks him to teach him some fighting techniques. Teaching is a euphemism for a serious match. The swordsman declines. But the daimyo shows interest, and at his urging the swordsman finally agrees to fight with wooden swords. Out in the garden the two men face each other and a moment later strike with their wooden swords hitting each others body, apparently simultaneously.

The swordsman says, Did you get that?

The r nin says, It was a draw, looking exceedingly pleased that hes had a draw with a famous swordsman.

nin says, It was a draw, looking exceedingly pleased that hes had a draw with a famous swordsman.

But the swordsman calmly says, No, I won.

Upset and angered, the r nin asks for a rematch. He gets it, and exactly the same thing happens. The two mens blows appear simultaneous.

nin asks for a rematch. He gets it, and exactly the same thing happens. The two mens blows appear simultaneous.

Exactly the same exchange occurs again: The r nin says it was a draw, and the swordsman says he won.

nin says it was a draw, and the swordsman says he won.

The r nin becomes outraged. And the daimyo shows greater interest, half disbelieving what the swordsman has said. The r

nin becomes outraged. And the daimyo shows greater interest, half disbelieving what the swordsman has said. The r nin now insists on another match this time with real, steel swords. The swordsman declines but is again overruled by the daimyo. But as soon as the two men face each other, the fight is overwith the r

nin now insists on another match this time with real, steel swords. The swordsman declines but is again overruled by the daimyo. But as soon as the two men face each other, the fight is overwith the r nin keeling over, his head split in two. The swordsman walks up to the daimyo and shows that part of his body which the r

nin keeling over, his head split in two. The swordsman walks up to the daimyo and shows that part of his body which the r nins sword seemed to have struck. Part of his outer jacket is slightly cut, but not the clothes underneath, let alone his flesh.

nins sword seemed to have struck. Part of his outer jacket is slightly cut, but not the clothes underneath, let alone his flesh.

Such may be your images of the samurai: a fantastic killing machine or a preternatural user of the sword. They are, indeed, typical of the stories of samurai endlessly spun in modern Japan as well, albeit of a particular period. I cite them at the outset, however, to make two things clear.

First, this book, Legends of the Samurai, aims to show the changing ethos of the Japanese warrior from a variety of angles, so it does more than assemble tales of samurai demonstrating their martial skills. Such tales, in fact, make up a minor portion of the volume, mostly collected in Part One.

Next page

nagon, vol. 2. But where I found his equivalent unacceptable, as in calling the second-ranking officer in the Imperial Police assistant director, I devised my own. For different translations of certain titles, see Karl Fridays book on the early samurai, Hired Swords.

nagon, vol. 2. But where I found his equivalent unacceptable, as in calling the second-ranking officer in the Imperial Police assistant director, I devised my own. For different translations of certain titles, see Karl Fridays book on the early samurai, Hired Swords.